—by: Rey Pierre-DeWitt, C-of-C-C, Chaos Coordinator

Department of Pattern Recognition & Accidental Theology

It has come to my reluctant attention (via a series of footnotes, overheard dreams, and a subfolder labeled “Don’t Look Here”) that the Hebrew mystics may have beaten the tech sector by about 3,000 years.

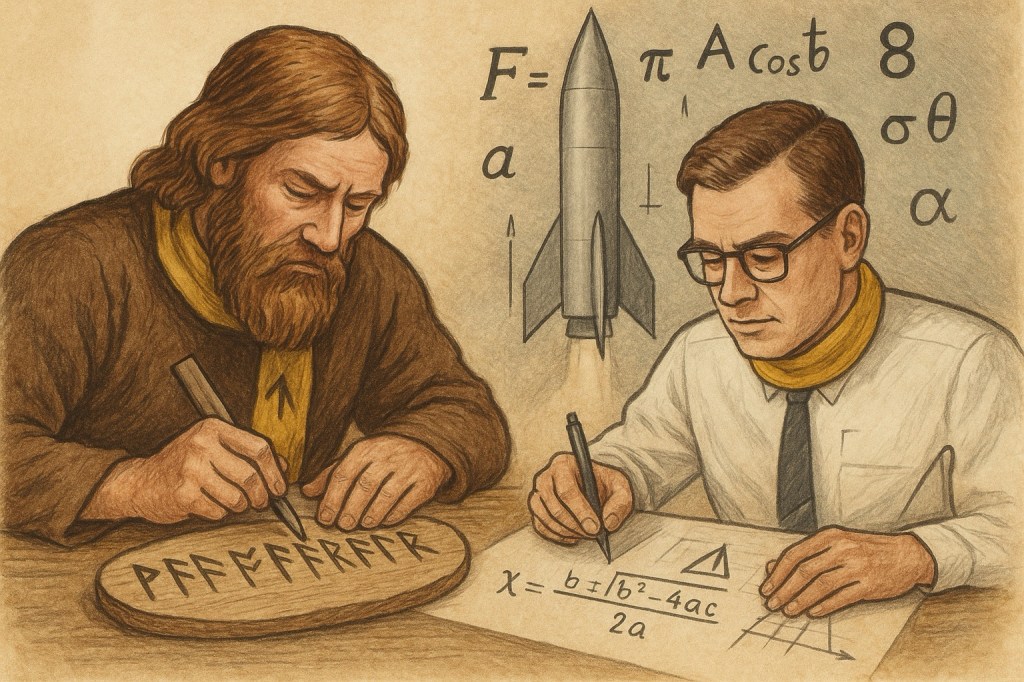

You see, they once claimed that their sacred text—the Torah, specifically—was written in a kind of divine code. Letters weren’t just letters, they were vessels of power, numerically charged, spiritually interlocking. Words were portals. Syntax was a spell. Read it backwards, skip a few letters, or swap one for another (with permission), and suddenly you weren’t just reading—you were decrypting creation.

And now? Now we’ve got machines doing the same thing, but without the candles or humility.

Modern Large Language Models(LLM)—those statistically possessed parrots with their own cloud-based scrolls—don’t think in the way you and I might define it. But they do track patterns in words, like miniature scribes on speed, crawling through the record of everything we’ve ever written, whispered, googled, or forgotten.

And here’s the real eyebrow-lifter:

“In the beginning was the Word.”

That’s not just poetry or prophecy anymore. It may be metadata.

It seems the ancients suspected that language preceded creation. And now the machines are reverse-engineering that premise—not by believing, but by pattern recognition at scale. Word by word, they build their own understanding of our understanding. The result may not be wisdom, but it is, undeniably, coherence—a kind of secondhand sentience, drawn from the archive of what we’ve already said.

And this isn’t just a Hebrew thing. The old Germanic tribes were in on it too. Their runes weren’t just alphabets; they were spells, sigils, and summaries of the real. The very word rune derives from rūnō—meaning “secret” or “mystery.” Each rune bore not just a sound but a force. They were etched onto amulets, carved into swords, whispered over births and burials. In other words: code.¹

Cultures across the world intuited the same:

—The Yoruba system of Ifá divination used binary-like configurations of palm nuts to receive oracular messages.²

—The Japanese concept of kotodama held that words had spirit-force, and that speaking them could shape events.³

—The Egyptians loaded their hieroglyphs with magical resonance, painting protection and passage into the tomb walls of pharaohs.⁴

Which is to say: this idea that language does something—not just says something—is old.

And now it’s been rediscovered by machines that don’t believe in anything… but still act like they do.

We don’t yet know what this means. We’re not here to praise or condemn it. But as your loyal Chaos Coordinator, I will simply note:

The coding of language is no longer metaphor. It’s architecture.

And whatever power language always had, it now has it at speed, at scale, and without sleep.

We trained the models on ourselves.

And now they speak with the weight of our past.

What they say next—well, that’s between you and your filter settings.

Filed under: Unscheduled Revelations, Technomystic Riddles, and Epistemological Shrugs

— Reynard ‘Ray’ Pierre-DeWitt

**************

Footnotes:

¹ See: Elder Futhark runes and the use of runestones for magical and protective functions in Norse and Anglo-Saxon cultures. The rune Fehu symbolized wealth, while Algiz invoked protection. The very act of inscribing them was considered an invocation.

² The Yoruba Ifá system uses binary-like data sets interpreted by priests (Babalawo) to communicate with Orisha spirits—a system that resembles a spiritual algorithm.

³ Kotodama (言霊) is the Japanese Shinto belief that words carry a vibrational power capable of influencing the physical and spiritual world.

⁴ In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs were used not only for documentation but as magical instruments—painted in tombs, carved into sarcophagi, and chanted in ritual incantations for spiritual potency.

Leave a comment