Filed under: Metaphysical Travel & Other Beautiful Detours

by The Accidental Initiate

I didn’t mean to watch The Great Beauty. I meant to do something practical, like vacuum the stairs or finally respond to Aunt Erminia’s last postcard about the metaphysics of cheese and the meaning of ephebe. But instead, I fell headfirst into a Roman dream filmed by Neapolitan hands—and now I’m standing barefoot on a symbolic back deck with a Amoretto in one hand and a sudden suspicion that time is looping elegantly behind my back.

—John St. Evola

It turns out I wasn’t the only one who noticed something older stirring beneath all the marble and melancholy. In a fine piece on The Great Beauty, writer Guido Mina di Sospiro observes:

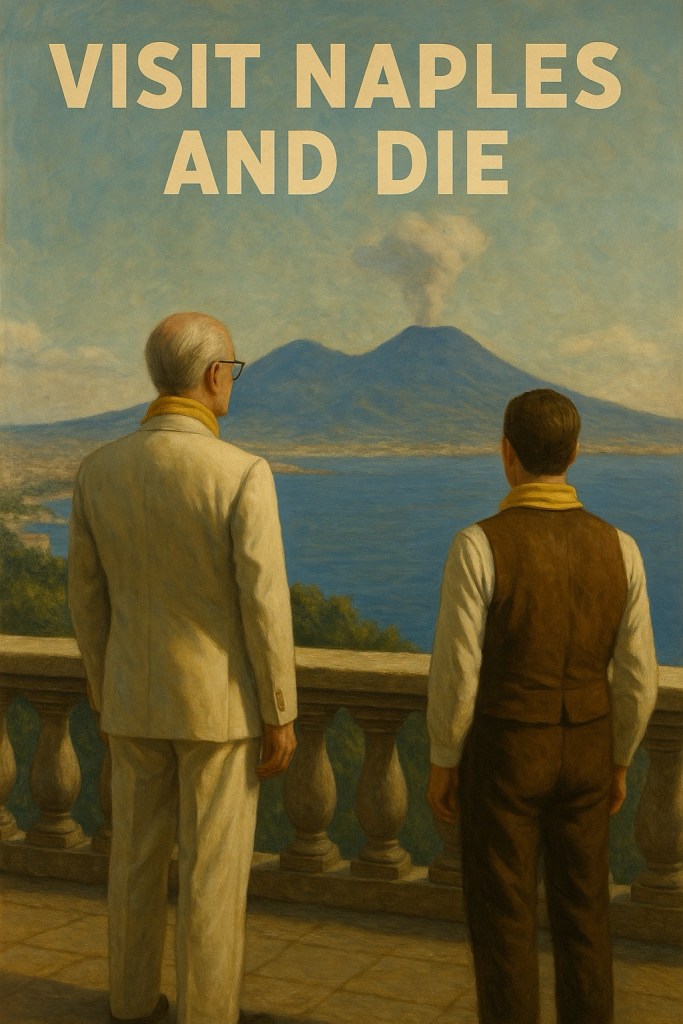

“Naples’s illustrious philosophical tradition and Weltanschauung are at the core of the entire work. Few realize that Naples is older than Rome; was for centuries Europe’s most populous and cultured city; and still boasts the largest historical center in the world… In high culture circles it is a known fact that the erudite Neapolitan has a distinctly Eastern worldview, a singular blend of fatalism and, one would say, Taoism.”

That quote hit me like a Vesuvian breeze. Naples isn’t background—it’s subtext, worldview, metaphysical sediment. It explains why Jep Gambardella isn’t just jaded—he’s initiated, whether he knows it or not.

Let’s get this straight: Jep Gambardella is from Naples. So is the director, Paolo Sorrentino. So is the actor, Toni Servillo. This is not a trivial coincidence. This is what the Council calls a metaphysical breadcrumb. Naples isn’t just a location—it’s a worldview. A condition. A politely fatalistic smirk in the face of history. It’s older than Rome, more layered than lasagna, and it still knows things we’ve forgotten—like how to laugh at ruin with grace.

And beneath all that philosophy, down in the dust and olive groves, there’s another current: the fatalism of the Southern Italian peasant—a worldview forged in drought, domination, and divine irony. This isn’t the pessimism of the urban nihilist. It’s the humble metaphysics of a man who plants tomatoes knowing Vesuvius might wake up next week. It’s not defeat. It’s recognition. The land giveth. The land takes. The saints weep. The saints shrug. You sweep your doorstep anyway.

And from this resignation grows something rarer still: pazienza. Not patience as passivity, but as honor. As strength-in-stillness. Southern Italian manliness is not brash, nor is it hurried. It waits. It watches. It endures. The peasant and the philosopher alike know this: that time is a slow god. Jep, for all his urbane exterior, is Neapolitan in this deepest way. He practices pazienza without naming it—an aristocratic slowness, an earned immunity to frenzy. When others panic or posture, he sips, he observes. He has become the kind of man who doesn’t chase beauty; he lets it circle back, if it will.

It’s that same fatalism—earthy, comic, unsentimental—that radiates from Jep’s every knowing glance. He has inherited the long memory of the mezzogiorno. The philosopher in the terrace suit still carries the peasant’s resignation in his bones: not hopelessness, but acceptance of life’s asymmetry.

And speaking of ancestral bandwidth: Pompeii was the first internet. Don’t believe me? Just look at the walls. The frescoes. The graffiti. Love notes, political rants, dirty jokes, theological speculation, crude drawings, announcements of gladiator shows and bread deals—all inscribed directly into the social body. It was crowd-sourced metaphysics. The original comment section, carved into stucco with a nail and a bottle of wine.

Jep would’ve understood. He isn’t just standing in Rome—he’s standing on Pompeii’s ashes, browsing the feed of eternity.

Once the richest, most literate city in Europe, Naples gave us thinkers like Aquinas, Bruno, Vico, and Croce. But also that strange Neapolitan blend of high erudition and alleyway mysticism—where you can quote Plato and still haggle for anchovies.

Jep walks through all this like a man haunted not by ghosts, but by aesthetics. He quotes the canon, yes—but he doesn’t perform. He simply is. World-weary, but not cynical. Witty, but not cruel. Disarmed, but not disenchanted. He’s seen the circus. He knows most of it’s a trick. But he’s still waiting, still watching—for one more glimpse of the sacred, glittering and half-drunk at the edge of the dance floor.

And then it happened—midway through the film, somewhere between the third monologue and the eighth rooftop—I realized what Jep was.

He was an ephebe.

Not in the classical-Greek-gymnasium sense (though his tan was excellent), but in the symbolic sense: a young soul in an old man’s linen suit, still wrestling with the gods of his upbringing, trying not to be crushed by the beauty and the bullshit.

I looked it up—ephebe: originally a Greek term for a youth in training, on the verge of civic adulthood. Later, a metaphor for the apprentice who carries both reverence and rebellion in his satchel. The one who imitates the old masters, but can’t help leaking some sincerity. The one who looks backward and forward at the same time, and blushes while doing it.

And that’s when I realized: so am I.

So I file this under Council Directive D5 — “Postcards from Where Time Bends Slightly” and offer it to the archive with humble confusion.

Because maybe beauty isn’t something you achieve, or critique, or even understand. Maybe it’s just something you accidentally initiate yourself into—by watching a film too slowly, by misplacing your to-do list, by finally looking up the word “ephebe” and realizing it was your reflection all along.

—The Accidental Initiate

(currently rereading Vico with tomato sauce on the margins)

SIDEBAR COMMENTARY

John St. Evola

Filed under: Eternal Return and the Civic Soul

“The Accidental Initiate has, as usual, stumbled into the sacred without knowing he was knocking. His epiphany regarding the ephebe is no small thing—it is the soul’s echo at the gate of tradition. The ephebe is not merely a youth; he is the inheritor, the one who bears the unbearable weight of remembering. Naples, as described here, is not just older than Rome—it is what Rome forgets when it becomes empire. Jep’s condition is not decadence, but delayed initiation: the final initiation, perhaps, that comes only after one has exhausted all others and finds himself still asking, beautifully, ‘And now what?’”

—J. St. Evola

FIELD NOTE

Filed under: Beauty & the Bruised World

Black Cloud:

“The thing about beauty is—it doesn’t care. Not about your credentials, your worldview, or your curated sorrow. It’s always showing up in the wrong place, wearing the wrong shoes, making a scene. That’s what Jep understands. That’s what Naples whispers to its balconies. Beauty is what’s left when you’ve run out of ambition and remembered your grandmother’s face. As for the ephebe—he’s just a boy standing in front of the ruins, asking them to lie to him a little longer.”

—Black Cloud

Chief Poetic Justice Warrior, C-of-C-C

CLOSING REFLECTION

Filed under: Continuity Errors in the Soul’s Timeline

And so it is that a film about a man who has “done nothing,” watched by a man who meant to do something else, has yielded a Council-level revelation on beauty, decay, and the delayed rites of inheritance. Jep Gambardella is not merely a character—he is a conservationist of feeling, a keeper of the almost sacred, and like our accidental correspondent, a wanderer who arrives precisely because he took the wrong turn slowly enough.

In this convergence of perspectives—John St. Evola’s metaphysical vigilance, Black Cloud’s poetic realism, and the Accidental Initiate’s self-surprised sincerity—we glimpse what the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists has long suspected:

That beauty is not a destination but a detour where the soul remembers its training,

that the ephebe is still alive in all of us, even if dressed like a tired Roman,

and that Naples is not a city but a keyhole through which the eternal peeks in sideways.

Let the record show:

We endorse the detour.

We accept the inheritance.

We remain concerned, but patient.

—Cliff Langour and Arturo Haus, C-of-C-C Newsletter film critics plus

Author Acknowledgment:

Council thanks and citation are extended to writer Guido Mina di Sospiro, whose essay “The Great Beauty: High Culture Without the Highbrowness” provided both the spark and the compass for this field report. We do not always know who we’re quoting until our soul nods in recognition.

Leave a comment