A Brief Defense of Being Wrong About Everything New, On Principle

—Peter R. Mossback, C-of-C-C Athwart Historian

Let the record show: I was against the wheel.

I mean, who needed all that rolling? Sure, it was nice not to drag your yaks across gravel anymore, but it gave people ideas. And ideas lead to innovation, and innovation leads to touchscreen thermostats that lock you out of your own house because your finger isn’t “warm enough to be recognized.”

Let us remember, friends of the Council, that humanity has always had the good sense to resist progress. We’ve been proudly and spectacularly wrong about every major development in the human saga. The printing press? “Will ruin memory.” The telephone? “No one will want to hear bad news immediately.” The Internet? “Just a passing fad for cat pictures and dial-up dating.”

And don’t get me started on the microwave. We once feared it would scramble our molecules—now we use it to revive coffee thirty-seven times in a row without a hint of shame.

I say: good for us! Being wrong is tradition. Being suspicious is heritage. Being resentfully confused is, in its own way, a form of folk wisdom.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FUTURE DISASTERS (AS PREDICTED IN ERROR)

1830s – Railway travel will cause the uterus to fly out of the body at 50 mph.

1890s – Electric lighting will blind everyone and confuse the roosters.

1920s – Radio will lead to mind control and jazz addiction. (That one might be true.)

1950s – Television will destroy literacy and melt children’s bones.

1980s – Personal computers will be too confusing for the average person.

1990s – The Internet will collapse under the weight of… e-mail.

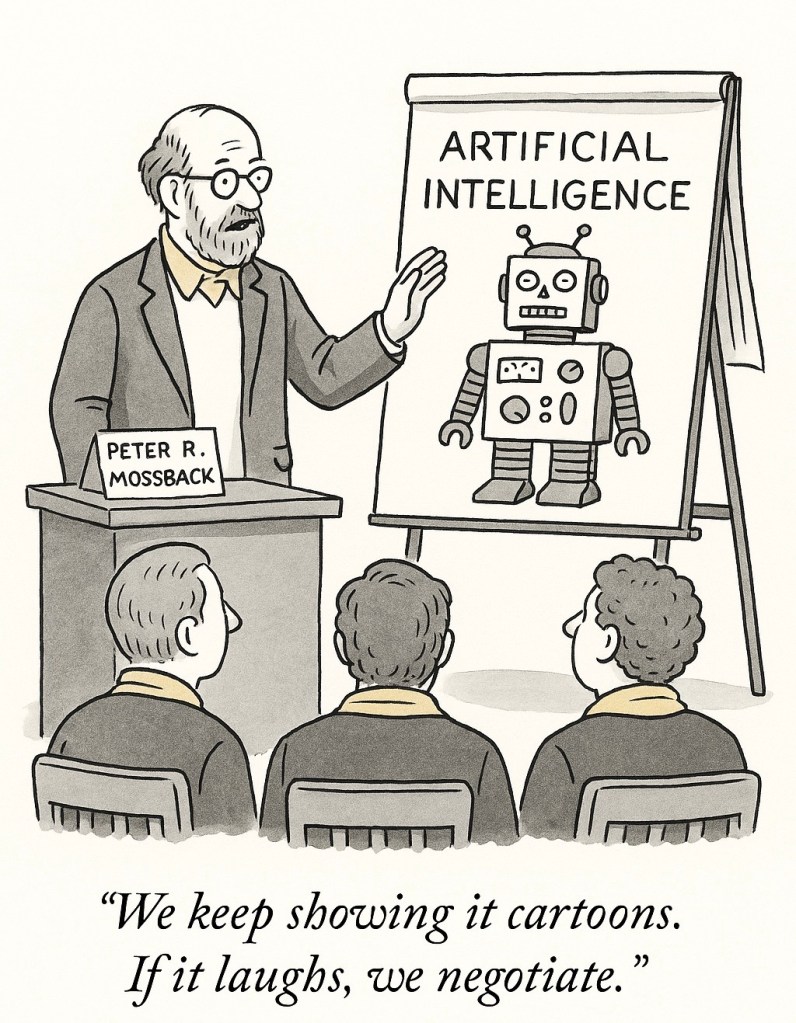

2020s – AI will enslave us.

2030s – AI will replace us.

2040s – AI will feel bad about it and host a candlelight vigil in our honor.

MY POINT IS THIS:

Every time the future came galloping toward us on some sleek silicon steed, a brave few of us stood in the road, yelling, “YOU’LL CATCH YOUR DEATH!” We were ignored. And we were right to be ignored. But we were also right to scream.

Because someone has to.

Someone has to keep standing still. To be the moss that testifies to the water’s flow. To lean back while the world leans in. That someone is me—Peter R. Mossback. The man with moss on his back, mildew on his boots, and a well-worn typewriter that types one key at a time. Slowly. With suspicion.

I say, let the youth chase their dreams in goggles. Let the future upload itself to a drone. I’ll be here in the stream, growing my metaphor, warning everyone that the toaster may be listening.

And if I’m wrong?

Good.

That just means I’m doing my job.

Postscript:

If you’re reading this on a smartphone, shame on you.

If you printed this out, laminated it, and pinned it to a corkboard with a brass tack, congratulations.

You may be ready for the Manual for Metaphysical Traffic Control, Second Edition.[2]

ADDENDUM: WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED

(Filed by Peter R. Mossback while polishing his spectacles with a wool sock)

You see, while I held the line (heroically, I might add), history had the audacity to continue. And each of those missteps—each terrifying newfangled thing—bore fruit. Not always sweet. Sometimes fermented. Occasionally hallucinogenic.

So, in fairness, I offer the following:

Railway travel (1830s)

We feared it would eject our innards.

Instead: It stitched together nations, turned lovers into long-distance poets, and made the horizon feel local.

But also: We lost the ache of distance, the holiness of absence. Intimacy became timetabled. The soul was never meant to arrive so fast.

Electric lighting (1890s)

They said it would blind us and disturb the poultry.

Instead: It kept factories running and dreams glowing. Roosters adjusted; poets stopped fearing nightfall.

But also: We did go blind—not in the eyes, but in the circadian soul. We forgot the stars. Darkness became waste instead of wonder.

Radio (1920s)

We thought it would turn us into jazz-addled zombies.

Instead: It gave voice to presidents, crooners, and baseball. It taught us to listen for ghosts in the static.

But also: The ghosts never left. Disembodied speech became the new oracle, and lies learned to travel at the speed of swing.

Now I won’t say I’ve changed. That would be unconservationist. But I’ve begun to suspect that resistance itself is a kind of participation.[1] That perhaps the act of standing still lets others know which direction they’re running.

Television (1950s)

They said it would melt children’s minds.

Instead: It invited the world into our living rooms—and reminded us we weren’t alone when the astronauts took flight.

But also: We stopped asking the world to visit in person. The flickering box became our fireplace, but no one told stories anymore. We watched, and forgot to remember.

Personal computers (1980s)

Too complex for ordinary folk, they said.

Instead: They turned kitchen tables into offices, and solitaire into a spiritual discipline.

But also: The complexity hid in plain sight. We outsourced memory, then judgment, then ritual. The ordinary folk became technicians of their own unraveling.

Internet (1990s)

It was supposed to collapse under cat photos.

Instead: It collapsed something else: time, distance, and the myth of being unreachable.

But also: We lost our edges. We blurred into each other, pixel by pixel. The village reappeared—but without boundaries, without silence, without the mercy of forgetting.

AI (2020s and beyond)

A threat, a ghost, a Promethean dare.

Instead: It wrote this paragraph you’re reading, which I may or may not have edited with a pencil stub and a raised eyebrow.

But also: It gave us what we asked for—a reflection—but not what we needed, which was a face. It told us who we sounded like, but never who we were. It made mirrors out of minds.

CODA: A SHIFT IN THE STREAM?

So no—I haven’t joined the future. But I did nod at it once, across a room full of humming machines.

And it nodded back.

It had my voice.

But it said something kinder than I expected.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] As D. Graham Burnett writes, “The humanities, in their fragility and contingency, may yet outlast the systems that render them obsolete—not by resisting change, but by haunting it.”

[2]Burnett notes that AI may supersede the need for humanists even as it scavenges their methods—suggesting the humanities might survive “not as a bulwark, but as a kind of slow-burning satire, a whispering resistance embedded in the code itself.”—D. Graham Burnett, “Will the Humanities Survive Artificial Intelligence?” The New Yorker, April 26, 2025.

Leave a comment