By: The Accidental Initiate

Someone suggested that the final issue of The Whole Earth Catalog should end not with tools—but instead be a novel.

And so it did: Divine Right’s Trip by Gurney Norman—a countercultural road-epic about a man in a VW bus confronting ancestral ghosts and Appalachian roots. It wasn’t tacked on at the end—it was woven throughout the Last Whole Earth Catalog, scattered like narrative breadcrumbs between how-to guides and solar cooker ads.

I’ve never forgotten that. Because it reframed the entire project. The Whole Earth Catalog wasn’t just a guidebook—it was a myth in serial format. Scattering the last edition with fiction made the quiet point: all those tools, communes, diagrams and dreams weren’t random. They were chapters in an epic. Not a how-to manual. A story. Maybe even a scripture.

Which brings me to a question I still can’t stop asking:

Do we live first, then write the novel to make sense of it?

Or are we acting out something older—racial, ancestral, civilizational—and only later realize we’ve been playing our parts all along? Are we the story enacting the myth?

Divine Right’s Trip follows a familiar American archetype: the wanderer, the seeker, the accidental initiate, the legal immigrant from the time when America needed strong backs. The same figure drifts through Kerouac, Arlo Guthrie, Huck Finn—and half the Council’s late-night arguments. We think we’re improvising. But it starts to feel suspiciously like myth. We’ve been on the road since our great grandfathers and great great great grandfather’s left Europe.

***

Jeff Bezos once called The Whole Earth Catalog “the internet before the internet.” He credited it as inspiration—and it shows. Amazon took the Catalog’s basic premise—access to everything—and retooled it into a sleek, unrelenting fulfillment engine. From fantasy to the all too real.

But that’s where the trail forks:

The Catalog gave you tools to change your life. The Catalog encouraged autonomy. Amazon ensures dependency. Amazon gives you products to reinforce your habits. But let’s be objective,

🎶You can get nearly everything you need and want at Alice’s—I mean Bezo’s Amazon.

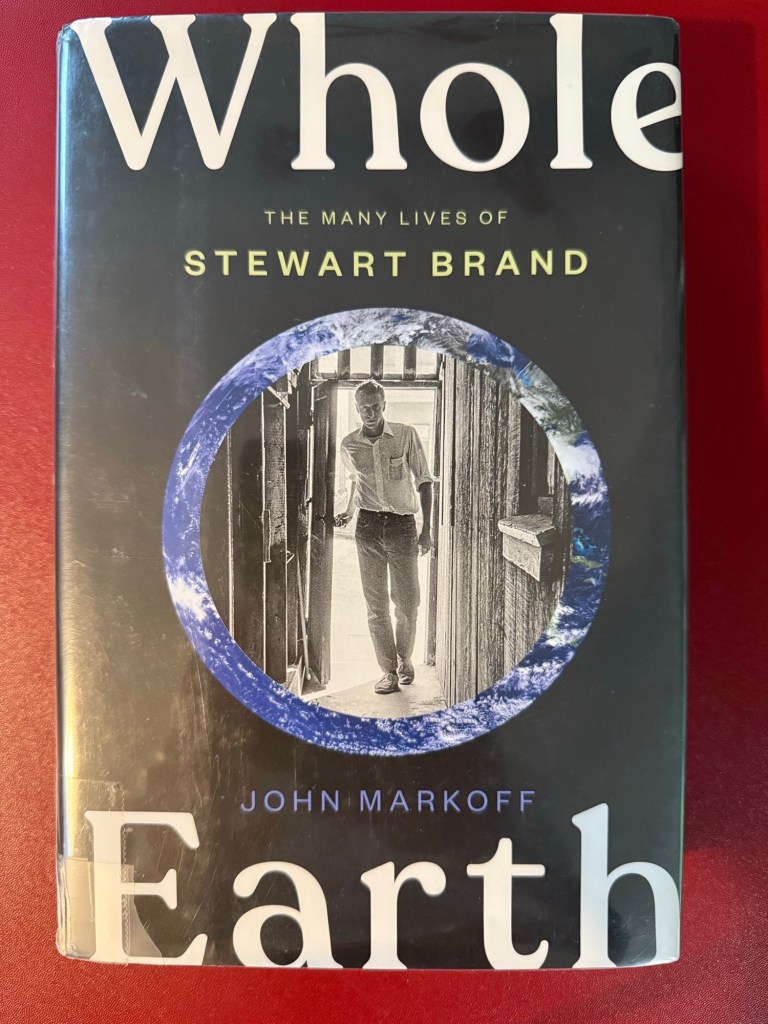

It did fulfill in part, the dream of Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog. This guy, Stewart Brand was a true visionary and real American character. Read on.

“Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?”

Before satellites gave it, Stewart Brand called it forth—

a vision of unity, summoned by imagination alone.

You didn’t browse The Whole Earth Catalog to get stuff faster. You browsed it to think differently. To be reminded that a book on goat husbandry might radically alter your path. That an index of tools could double as a blueprint for living.

So yes—materially speaking—Amazon is the Catalog in late-capitalist drag.

But spiritually? It’s the ghost of a ghost.

Which brings us, naturally, to Alice’s Restaurant.

🎶You can get anything you want at Alice’s Restaurant…”

—Arlo Guthrie

That song—part satire, part elegy—was about resisting the draft by becoming too absurd to categorize. It was protest by way of hospitality. And like the Catalog, it suggested that you could resist the Machine by making a meal, opening your door, and naming the madness aloud.

This, too, is the work of the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists.

We are not revolutionaries.

We are not influencers.

We are the ones who:

Grill with dignity. That is, backyard sausages and also those hot dogs who think they know it all.

We preserve lost recipes and dangerous ideas.

Keep the yellow neck gaiter ironed and ready.

Mumble Blake at the breakfast table.

Host the ghost of Edith through kitchen sounds.

Plant our feet in stories others forgot.

And if you press us hard enough, you’ll hear a whisper from the bottom drawer of the filing cabinet:

“I would prefer not to.”

Yes—Bartleby. The Scrivener.

Our patron saint of passive resistance and early hero.

He saw the Machine coming long before the rest of us. He worked inside it. Wrote for it. Filed its memos. And then—he stopped. Not with drama or violence, but with steady refusal. Until even his silence became a form of truth.

He left no manual.

No memoir.

Only the ache of a deeper question:

What if refusal itself was the last form of authorship left?

We don’t know if Bartleby was writing a novel.

But we know he ended one.

And maybe that’s the real secret.

Divine Right’s Trip wasn’t just a novel interspersed through the last issue—it was a mirror.

A model.

A life scattered like a thread through a manual.

A destiny composed in alternating lines—with instructions, composting toilets, and unspooled myth.

Because that’s how we live:

Half tool, half tale.

Half inherited, half improvised.

To preserve the dignity of the misfired gesture.

We’re not entirely free. But we’re not entirely scripted either.

We are written—yes—by biology, by history, by language.

But we still get to choose where the paragraph breaks.

We still get to write in the margins.

We still get to laugh in the footnotes.

Maybe this is the novel.

Maybe we are the novel at the end of the Catalog.

Not because we authored it from scratch—but because we recognized it in time.

And tried to make something beautiful before the narrative unraveled.

Of course, like most human projects, it didn’t go exactly as planned.

Revelation became detour. Myth became footnote.

And a few too many dreams ended up filed under Gone Awry—Black Cloud’s column of unintended consequences, poetic derailments, and noble stumbles.

Maybe that’s the Council’s true calling:

To bear witness after the plan collapses.

To patch the myth with duct tape and whisper: Keep going anyway.

Do we write the novel?

Or does the novel write us?

We may never know.

But we’ve got the gaiter, we grill,

and we try to save the last annotated edition of everything that almost worked.

And that’s enough to carry the story one more page.

⸻

But wait, there’s more—

And then there was the Demise Party which came at the end of the Last Whole Earth Catalog

That night, Stewart Brand offered $20,000 to fund the “best new creation.” What happened next wasn’t a planned legacy—it was an accident of spirit. A penniless activist named Fred Moore took the mic, burned a dollar, and argued that what mattered wasn’t the money—but the way we empower each other by sharing information.

He got the money anyway.

Moore—an idealist uncomfortable with capital—used the funds to support Project One, a ragtag warehouse collective in San Francisco. There, in a final act of poetic recursion, Doug Engelbart’s mainframe computer (the same one that ran the early internet prototype) was salvaged and repurposed for community use—paid for, full circle, by a grant born from Whole Earth money.

From this tangle of good intentions and organized improvisation, Moore launched the Homebrew Computer Club in 1975. A meeting of hobbyists and hackers who believed computing should be open-source, communal, and liberating.

Among its members: Steve Wozniak. Steve Jobs. The future of Silicon Valley.

Stewart Brand didn’t create the personal computer revolution. But he helped fertilize it—with story, trust, and a willingness to hand someone else the next page.

There’s a deeper irony here too—because as it turns out, The Whole Earth Catalog didn’t just predict the internet. It became it.

Years later, Jeff Bezos would say that The Whole Earth Catalog was a formative influence—calling it a “paperback Google.” Its DNA lives on in the idea of the marketplace as knowledge engine, tool chest, and cultural weather vane. If Amazon is a shopping empire, it was born in a barn-raising of dreams.

Somewhere between counterculture and code, a line got crossed.

The catalog became the algorithm.

The back-to-the-land dream became the delivery drone.

And the handmade, homespun knowledge of the margins was swept into the cloud.

And yet, like in Alice’s Restaurant, we keep going back to the same church basement of memory, singing the same absurd verses, knowing that the whole thing isn’t quite linear. We aren’t living the epic. We’re performing the epilogue over and over again, until the structure itself starts to feel like liturgy.

Or maybe prophecy.

⸻

Here at the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists, we’ve been watching it unfold from the footnotes. We suspect that maybe this—what we’re doing, what you’re reading—is the novel they left unfinished. Not a proper story, but a field guide disguised as narrative, passed from reader to reader like a marginal note in a sacred text someone spilled soup on.

We were told we’d live in a world of tools. But what we needed was myth, permission to believe that the fragments still pointed somewhere. Maybe not to utopia. Maybe not even forward. But somewhere worth returning to.

And that’s the irony, isn’t it? You grow up thinking you’re in a manual. Turns out, you’re in a novel. Worse—an unfinished novel with a bunch of contradictory drafts, handwritten in the margins, annotated by people who never agreed on what the story was about in the first place.

But that’s where the Council comes in.

We read what others skip. We file what others toss. We trust that even the worst ideas sometimes come back with good timing and better typography. And we’ve seen this before: how a burned dollar and a garage club can seed an empire. How life writes us, even as we scribble in resistance.

Which is why, in truth, this might not be a novel at all—but a commonplace book in disguise.

We collect what catches our attention. We underline what glimmers. We store half-remembered quotes, overheard jokes, recipes from the dead, and folk wisdom from imaginary cousins. We pin them to the bulletin board of Being—not because we know their meaning, but because they might mean something someday. This is how we learn to navigate: by noticing what others have forgotten to underline.

Like Bartleby the Scrivener, we’re learning to prefer not to comply with the expected ending. He haunts us. Inspired us. Maybe not always for the better. But he left a mark.

We don’t worship refusal—but we honor it. Especially when it comes with silence, slowness, or the dignity to say: “I’d rather not.”

⸻

So where does that leave us?

Maybe here:

Some lives are lived like catalogs.

Some like manuals.

Some like manifestos or memos.

But for me, Accidental Initiate—and for those of us still typing in the back of the pub—life is a novel. Not always well-written. Occasionally overwritten. But still… strangely beautiful in its structure.

We may have made up part of our lives. But the rest? It made us.

And in the end, like Black Cloud once said in the Gone Awry column:

“You think you’re writing a love song. Then you find out it was a weather report.”

This, dear reader, may have been our weather report.

But the climate? Still changing.

And the novel? Still unfinished.

And the commonplace book?

Still open.

AFTERWORD

By John St. Evola:

What a load of bilge. I think the Accidental Initiate has tripped one too many times—as Stewart Brand once admitted.

But AI did give us a few good anecdotes from Brand’s biography that will go in the C-of-C-Commonplace Book—our version of the Whole Earth Catalog which we never considered in that light until just now.

But wait, one more time.

If you stayed long enough there is one more revelation which we just realized. You could say it was accidental.

The man who called for the photo of the Earth from space to demonstrate that we are All stuck on this planet together and have to find a way of being better “Stewarts” or caretakers as the Bible says we must be—was named Stewart.

NOMEN EST OMEN!

(How was that for an ending to a novel.)

Leave a comment