⸻ by Peter R. Mossback, Athwart Historian

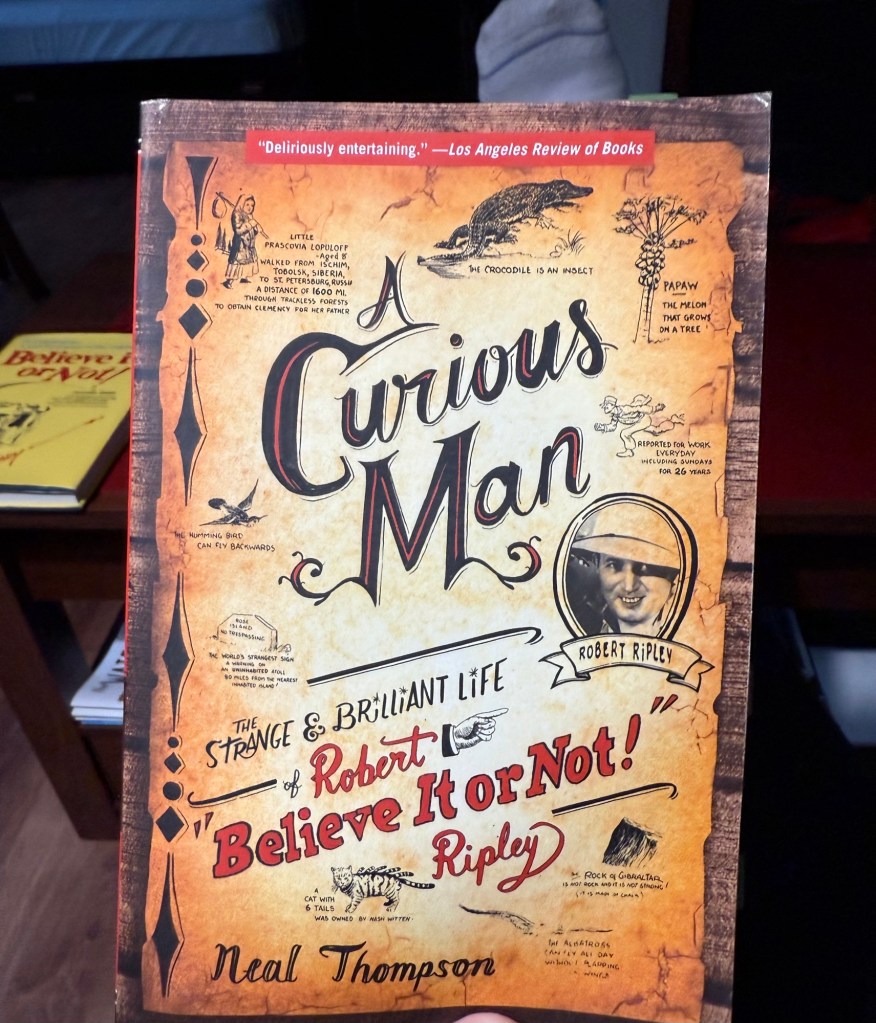

“In today’s world, it is hard to imagine an incarnation of such a man…”— from A Curious Man, by Neal Thompson

Editor’s Note – by John St. Evola

He once claimed to prefer the company of chipmunks. That line, buried in the footnotes of Ripley’s press bio, has always struck me as the key. Chipmunks are curious but cautious, obsessive collectors, attuned to the flickers of the unseen. Ripley was the same. He listened at the edges of belief, stashed away impossibilities, and built a house out of exceptions. In an age that rewarded smooth explanations, he chased the stutter, the bulge, the unclassifiable. This essay by Peter R. Mossback is a tribute not just to the man, but to the deeper American instinct—to gather strangeness, to question consensus, and to walk uphill when the world flows down.

Pete Mossback:

I would have dismissed him, once. A bucktoothed cartoonist hawking cheap thrills and twisted limbs. A drawer of dwarfs. A stutterer with a passport full of elephantiasis and conjoined trivia. I might have—had I not begun to notice that, in this most sterilized of centuries, Robert LeRoy Ripley stands out not as a purveyor of freakery, but as one of the last true conservationists of the nonrational.

He conserved oddity. Not by curating it safely behind glass, but by thrusting it into the center of American popular imagination with three words:

Believe It or Not!

A Crusade Against the Tyranny of “Reason”

In an era drunk on progress and positivism, Ripley roamed the earth collecting violations of neat categories. He gave platform to that which defied taxonomy, and thereby struck a quiet blow against the Enlightenment’s spreadsheet soul.

Born on Christmas Day (because of course he was), Ripley began his career designing tombstones and ended it with a radio broadcast that circled the globe. He liked the company of chipmunks, traveled to 201 countries, wore only bowties, and still used the front door of his boyhood home—as if to say the improbable should always enter through the front.

He also famously confessed:

“Why any one place should forever hold enchantment for the reason you are born there is a mystery. But like cats and birds we are pussy-footed and pigeon-toed and our footsteps lead toward home.”

“The Eskimo longs for his northern bleakness and his ice hut, the cowboy dreams of the wide open towns and prairies of the west, the old salt is looking out to sea. And down in the hold of many ships are dead Chinamen’s bones going home to China.”

Only a sentimental oddity like Ripley could romanticize repatriated skeletons with such grace. But in this too he conserved something fragile: the longing of the displaced, the soul’s homing instinct.

Believe it or not… the real string-pullers were trying to keep the world stitched together.

[This unsigned cartoon was discovered decades later beneath a collapsed trullo in Apulia, sealed in a rusted box with a marionette and a Latin Bible. Though unsigned, the style—and the pseudonym Anne O’Malley—gave it away.]

Against War, and the Men Who Craved It

Ripley’s instincts were not only personal but political. In the run-up to the Second World War, he publicly opposed U.S. entry, held firm as an isolationist, and was known to despise Roosevelt—whose grandiose New Deal ambitions and interventionist crusades reeked of precisely the sort of modernist messianism the Council distrusts.

He believed “the fear of Jehad has been upon the Christian world for ages”—a prescient recognition of the cyclical geopolitical specters haunting the West. And while he was often a captive of his era’s chauvinism, Ripley was no fool. In one breath, he voiced the anxious Western fear of “the fanatical Muslim.” In the next, he sensed—uncannily—the enduring fragility of empires built on misunderstanding.

Even more striking was his commentary on colonial Africa. He recoiled at the crude modernizing instinct of white Europeans.

“Stupid white people trying to change the age-old habits of the Africans,” he wrote in his journal.

And then, with brutal clarity:

“Missionaries are the curse of Africa, the same as they are the curse of the Islands of the South Seas. The black man of Africa in his savage state is a gentleman. Only when he starts to become civilized does he lose his character and become diseased, immoral, unhealthy, and criminal.”

The language is dated. The conclusion is questionable with qualifications. But the insight is crystalline. Ripley believed civilization was as likely to infect as to elevate. In this too, he stands firmly with the Council.

Ripley was, in Council terms, a race realist with an ethnographer’s eye. He made crude generalizations, yes—but he also traveled farther, looked closer, and listened longer than most men of his time. He respected what was distinct in every people he encountered: their customs, bodies, beliefs, and superstitions. His journals swing between patronizing description and genuine awe. Ripley may have seen race as real, but he did not see it only as hierarchical—rather, as a parade of difference worthy of astonishment, documentation, and—above all—preservation.

Odd Man In

Let’s not forget—he was weird. As one biographer noted, he was:

“A shy, goofy, portly, bucktoothed stutterer who becomes a world traveler, a multimedia pioneer, a rich and famous ladies’ man, and one of the most popular men in America.”

Ripley loved women, but mistrusted them—a contradiction that revealed itself in his fleeting romances and prolonged bachelorhood. He was drawn to the elegance of both Nordic and Asian beauty, favoring physical refinement and cultural mystery over what he viewed as the brash modernity of American women. Yet for all his affection, he kept emotional distance, suspicious of entanglements that might undermine his singular, globe-wandering pursuit of the unbelievable.

He never asked to be the American Everyman. But in making room for the misfit, the improbable, and the grotesquely true, he became one of the most honest mirrors we ever held up to ourselves.

And perhaps that’s the truest American thing of all. For what is America if not a sprawling pageant of glorious misfits, improbable characters, the outcasts of Europe—a republic founded by freethinkers and frontier cranks, extended by circuit-riders and snake-oil prophets, and preserved, in its deepest mythos, by the belief that oddity is authenticity?

He paid well, gifted generously, and kept close relationships with the strange souls who peopled his odditoriums. He sent money to the families of his performers. He treated staff as kin. He walked among the freaks not as a showman but as their archivist, benefactor, and shield. He was, in many ways, their Council.

Council Recommendation: Archive the Absurd

We are duty-bound to conserve not only nature’s biodiversity, but civilization’s eccentricity index. Ripley raised the absurd to an art form. He took grotesques, marginalia, and animalistic anomalies—and made them matter.

Let the academies wring their hands over “representation” and “problematic display.” Ripley understood long before the theorists that what we call deformity is often a form of resistance. And what we call belief is often just another name for memory.

He remembered what most people tried to forget:

That the world does not always add up.

That life contains footnotes that override the text.

That a man may be mocked for collecting oddities—until he is seen for what he is:

a preservationist of the impossible.

Pete and Bob.

Fellow travelers against the current—of water, fashion, and scientism. Two oddballs wading upstream toward the THE SOURCE, while rationalism drifts comfortably downstream. They gather moss and marvels in defiance of the Zeitgeist.

Filed under:

Unlikely Heroes, Anti-Rationalists, Cultural Memory, Bowtie Resistance, Pre-Digital Cosmographers, Isolationists We Admire, Freaks as Founders

BELIEVE IT—OR CONSERVE IT!

⸻Peter R. Mossback, Athwart Historian

Footnote

[1] All quoted material from Robert Ripley. Biographical context is drawn from A Curious Man by Neal Thompson.

L

Leave a comment