Gone Awry.

The Unintentional or Unfathomable Consequences of Human Endeavor

Graduate of the Professor Irwin Corey School of Rhetoric, which is a prerequisite for all of our writers on the C-of-C-C Newsletter (with the exception of Sgt. Pepé).

EDITORIAL NOTE

This column takes its provocation from Gregory Wolfe’s essay, Beauty Will Save the World, published in The Imaginative Conservative. Wolfe argues that politics and rhetoric grow out of deeper cultural soil—myth, metaphor, and spiritual experience—and that authentic renewal requires the imaginative vision of artists and mystics. In contrast, our present age has flattened Beauty into minimalism: user-friendly interfaces, child-proof surfaces, the cult of “simplicity.” What follows is Black Cloud’s attempt, in his usual roundabout manner, to wrestle with Wolfe’s vision while mocking our modern worship of the push-button aesthetic.

INTRODUCTION

Permit me, dear reader, to begin with an observation that should be obvious but is rarely spoken aloud: what we call progress today is less about man’s elevation than about his regression. It is not the ascension of Prometheus, but the pacifier of Pampers. Technology, in its present incarnation, does not challenge us to grow; it coddles us to remain children.

The Labyrinth:

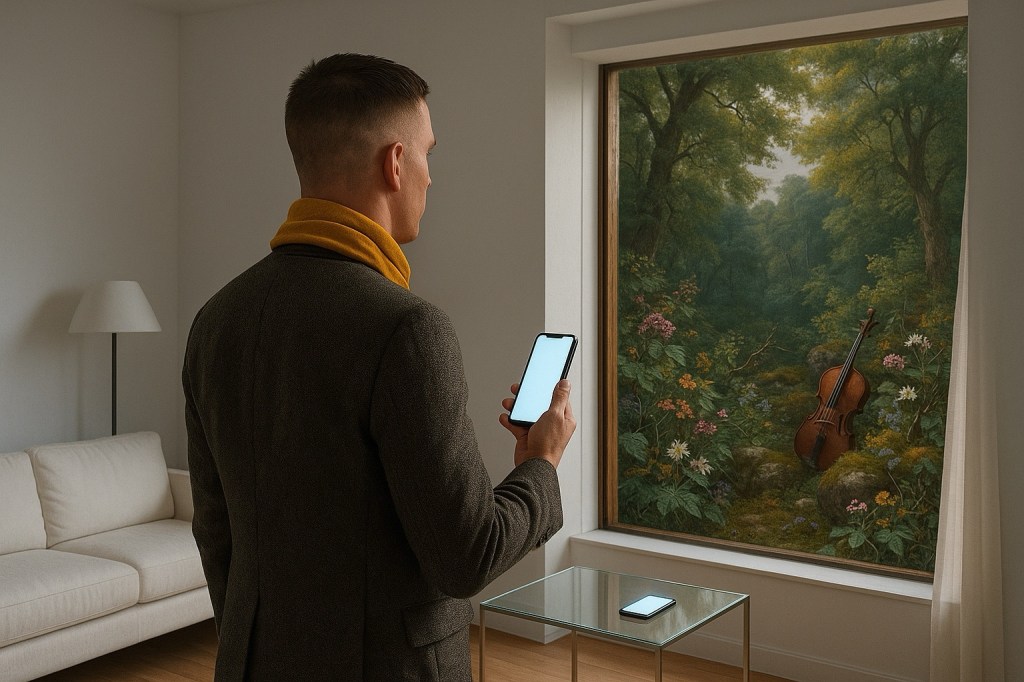

For the purposes of this reflection, let us grant that firearms, bridges, and even the glowing circuitry of handheld devices, et.al, are to be considered art. Why? Because in the modern world these are the things to which we attach our praise of Beauty. Where once it was cathedrals and symphonies, now it is pistols, overpasses, and iPhones that inspire awe. If these are our “artworks,” then our age has already declared that Beauty is not majesty or mystery, but simplicity: user-friendly, minimalist, child-proof.

Now, before I lapse into my usual cloud of words, let me say this as simply as I can: the great achievement of our age is not grandeur but efficiency. We take the raw stuff of nature and turn it into tools so easy that even the least trained among us can push the button. That is what designers now call “intuitive.” In other words—Beauty, in its modern minimalist disguise, has been redefined as simplicity: clean lines, bare surfaces, push-button ease.

This “intuitive” ease—praised by designers as Beauty—is but a euphemism for infantilization. It is a proud boast that “any idiot can use it.” And so the engineers of our time have built not monuments but toys, not instruments of growth but appliances of convenience. Consider the parallel: past ages painted cherubs with wings, symbols of childhood as divine innocence. Our age manifests its cherubs in blinking screens and self-driving wagons. Both point to the same lesson—“to enter the kingdom of heaven, ye must be as little children”—but only ours translates that into dirty diapers, tantrums, self-absorption, and consumer paradise.

Yet as Gregory Wolfe insists, “Art is not a diversion from politics, it is the soil from which politics spring.” Our civilization pretends otherwise, trading the roots of myth and metaphor for the pacifiers of gadgetry and the minimalist creed of less-is-more.

“The simple is not the whole, darling—it’s merely the bit that survived the editing. And minimalism? That’s just reductionism in a well-lit room pretending to be profound.”

—Mrs Begonia Contretemp, Why And The Wherefore Cohort [NVZ]

ON BEAUTY (WITH AN APOLOGY)

Is this Beauty? Perhaps in part. Elegance and simplicity are indeed aspects of the Beautiful. Yet in our day, Beauty is reduced to minimalism—the tyranny of smoothness and the cult of less—where ease passes for depth. The deeper strains—the baroque intricacy of nature, the melodies that demand years of practice, the stories that truly make simple sense (which paradoxically takes effort to achieve)—these are obscured.

And here I must confess my own hypocrisy: I, Black Cloud, cannot write simply either. My sentences wander with wings and stumble with spurs. But at least my convolutions admit that Beauty is not child’s play—it takes work even to say so badly.

Wolfe reminds us that “the beauty that saves is not the prettified or the saccharine, but the beauty that pierces us with its splendor, the beauty that wounds even as it heals.” That is why my own winding words, though hardly elegant, at least resist the narcotic of ease.

Here we return once more to Wolfe’s vision: politics and rhetoric rest on older foundations—myth, metaphor, and the spiritual vision of the artist and mystic. True Beauty, he says, lets us “touch the lines that run uninterrupted through life and death,” a hope that someone—or Someone—on the other side may be touching them too.

THE LESSON (FOR THE SIMPLETONS)

As Wolfe concedes, “My conceits will never serve to wake the dead… you may come enchantingly close, but in the end the door is shut.” Which is why the final word must be blunt.

Let me state it plainly, or as plainly as I am able: if your definition of Beauty is “easy enough for a child to push the button,” then you’ve confused art with appliance. Minimalism has duped us into thinking that less is Beauty itself—but that is the ugliest simplification of all. The world does not need more toys dressed up as truths. It needs adults—yes, even self-contradictory scribblers like myself—who can tell the difference between a lullaby and a life’s work.

And after all, the idea that Beauty will save the world is already a complicated idea. I mean—do you even know what that means? If you do, please explain it to me slowly.

The world was falling apart, so he handed it to Beauty and begged her to save it. She nodded, and asked if he had anything smaller.

Leave a comment