A Meditation on Solemnity, Seriousness, and Sacred Play.

Builder of Little Things. Believer in Bigger.

“Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly.”

— G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

I. The Miniature Cathedral

It began innocently enough. A rainy afternoon. A table full of popsicle sticks I couldn’t bear to throw out after eating coconut ice pops all summer. In addition to an old floor plan of Chartres Cathedral I’d once folded into my pocket on a visit to the Cloisters. And something like a whisper—childish, foolish, probably divine:

Build it.

“Clear enough for a child. Vague enough to require divine intervention.”

— Mrs. Begonia Contretemp, Council Commentary on Modern Diagrams

BUILD IT!

And so I did. Or started to. I’m still only halfway through the nave—though some days I fear I’ve made more progress as the knave.

It was a wholly unserious project. But the longer I worked, the more serious it became. Not in mood, but in meaning. And that’s where the trouble started.

II. The Weight of Things

There’s a superstition in modern culture—one I didn’t even realize I’d internalized until I found myself embarrassed by the joy I felt carving rose windows out of dyed tissue paper.

It’s the superstition that says:

Solemnity requires suffering.

Gravitas demands gravity.

Sacredness must be serious.

But as I glued a flying buttress into place using a dab of honey-scented wood glue and the tip of a toothpick, I remembered Chesterton’s line about angels. “They take themselves lightly.” That’s why they don’t fall.

And then I began to laugh—quietly, reverently, maybe even metaphysically. Because I realized: the cathedral was already floating.

III. Internal Correspondence (Imagined but Predictable)

Peter R. Mossback, our Council’s upstream historian, would likely scowl at my methods.

“Stone is stone,” he’d say. “You don’t preserve culture with ice-cream sticks and whimsy. You bear the weight.”

But I’d remind him: wasn’t it Christ who said “Unless you become like little children…”?

Dr. Faye C. Schüß would call this a mental hygiene experiment.

She’d warn of Terminal Gravitas Syndrome, a condition caused by overexposure to academic journals and policy panels. Symptoms include frown lines, acronym dependency, and the inability to skip.

She’d probably prescribe structured silliness and supervised glue-sniffing (non-toxic, of course).

John St. Evola would take it too far, as he always does.

He’d call it a metaphysical inversion:

“In building a cathedral with child’s materials, you invert the profane into the sacred, not by transgression but by echo.”

I wouldn’t disagree, but I’d still chuck a stick at his head.

IV. Medieval Secrets, Biblical Echoes

I dug deeper and found I wasn’t the first fool with a theology of play.

The medieval monks—God bless them—doodled cats chasing mice in the margins of psalters. Ecclesiastes reminded me: “There is a time to laugh.”

Psalm 2:4: “He who sits in the heavens laughs—”

Even Paul, that old curmudgeon, wrote that “God has chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise.”

Chartres was built as a cosmic book, yes. But it was also built by human hands. And surely someone dropped a chisel or told a joke or whistled while carving an angel’s foot.

V. Huizinga in the Workshop

While glue dried on the transept arch, I pulled down a copy of Homo Ludens by Johan Huizinga. He reminded me that play isn’t the opposite of seriousness—it’s the precursor to civilization.

“Play is older than culture,” he wrote, “for culture, however inadequately defined, always presupposes human society, and animals have not waited for man to teach them their playing.”

To Huizinga, play is voluntary, ordered, absorbing, and free—and civilization, religion, law, and even art all emerged from that primal matrix of creative absurdity.

He calls play “a stepping out of ‘real’ life into a temporary sphere of activity with a disposition all of its own.”

Which sounded to me a lot like church. Or childhood. Or a rainy afternoon spent building a cathedral out of scraps.

And so I built on. Lightly.

VI. Gravitas vs. Celebrity

In our time, celebrity has become a religion of faces and frowns. The High Priests are solemn. Po-faced. Poised. They intone with furrowed brows and disapproving glances. They act as though earnestness must always wear armor.

But here’s the question that floated up from my little cathedral:

Is seriousness always a sign of depth—or just a performance of it?

After all, Satan is serious. Pol Pot was serious. Bureaucracy is serious.

But angels—the ones still airborne—laugh.

And besides—if you’re wondering why we sometimes parody our own side, it’s simple:

The other side has already rendered itself beneath satire.

They parody themselves too perfectly, and without knowing.

So we study ourselves. We poke ourselves. We exaggerate and invert. Because we still believe in what we’re doing—and because the sacred should never grow too self-impressed to laugh.

Lost Comedians, Found Reverence

It occurred to me, midway through gluing a rose window frame, to ask:

Where have all the comedians gone who could joke without subverting?

Where are the ones who could play without poisoning?

I thought of Red Skelton, whose humor never sneered. Of Jean Shepherd, who could narrate the absurdities of ordinary life with affection, not disdain. Even Victor Borge, and Carol Burnett managed to be hilarious without spitting on the altar.

[Your taste may vary concerning these long gone comedians but the point holds.]

We used to joke as an embrace. Now it’s mostly deflection or assault.

Maybe it’s just easier to be ironic and corrosive.

Maybe mockery takes less courage than affection.

Or maybe our age has forgotten that love can laugh, too.

VII. Council Calibration Note

We at the Council are quietly but perpetually engaged in the metaphysical measurement of whimsy.

It’s a delicate ratio:

Too much whimsy, and you fall into farce. Too little, and you fall into the abyss of self-seriousness.

There must be a sweet spot, a kind of structural resonance between reverence and ridiculousness—the way a gothic arch balances pressure.[Perhaps this post was unconsciously inspired by this.]

We are always calibrating, adjusting for mood, tone, weight, risk. Not to be cautious, but to be precise. A glancing joke may redeem a paragraph. A poorly timed wink may ruin a witness.

Even Heidegger, in his own way, warned against the false gravity of Verfallenheit—the fallenness of being lost in the idle chatter of “the They.” What we seek, instead, is what he might call authentic lightness: a levity that lifts, not distracts.[And perhaps Heidegger was unintentionally funny with his natural use of those silly sounding German compound words, but he was, to a non-German speaker.]

🃏 A Word About the Joker

And then there’s the Joker—not the comic-book one with face paint and trauma, but the old-world one. The licensed fool. The jester who could speak truth to the throne without risking his head, because his office was outside the court’s solemnity.

It occurs to me now—I may have stumbled backward into that role.

Not out of strategy, but disposition and despair.

And further back still is the Trickster, the shapeshifter of myth who opens cracks in the world just wide enough for transformation to crawl through.

Maybe I’m not building a cathedral at all. Maybe I’m just widening a crack.

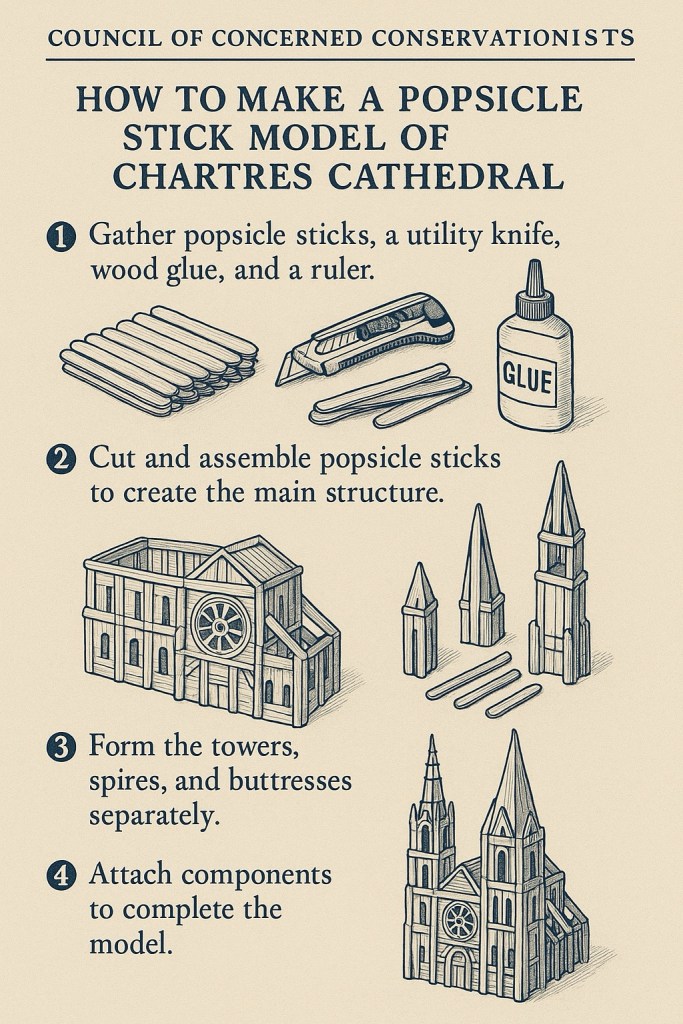

An early instructional diagram, likely monastic in origin.

Spelling erratic. Structure sound.

“I’ve seen worse Latin on tea towels. At least this one gets the flying buttresses right.” — Mrs Begonia Contretemp

VIII. Conclusion: Popsicle Theology

So here I am. A grown man hunched over a scale-model of Chartres made of pine sticks and prayer. A fool, perhaps. But one who remembers:

That play is not the opposite of reverence. That laughter can be an act of defiance against despair. That building something beautiful, even in miniature, is never a waste of time.

And if God looks down and sees me surrounded by scraps and glue and a half-built rose window, I hope He laughs. Not mockingly—but with joy.

Because if we’re ever going to fly again, we’ll have to take ourselves lightly.

—Filed from a workbench in the laundry room, beneath a crucifix and a coffee stain, by:

(Builder of Little Things, Believer in Bigger)

Afterword: On Flight and Fire

Filed later, when the glue had set and the silence felt theological.

I thought I had it figured out: angels take themselves lightly, and that’s why they fly. But like most things I think I’ve figured out, it kept unfolding.

It turns out, the matter isn’t so simple—and that’s fine. Because reverence rarely is.

See, not all angels arrive with a grin. Some descend like judgment. Some break open history. Some say, “Fear not” because fear is exactly what they’re invoking. But here’s what struck me while looking at my unfinished nave and wondering if I was more knave than craftsman:

Even when angels come grave, they don’t come grim.

They’re never smug. Never heavy with themselves.

Their weight is mission, not ego.

So maybe there’s no contradiction at all. Maybe it’s contrast—and contrast is the best place to look for meaning. Angels don’t fly because they’re funny. They fly because they’re free of self-regard. Their gravity isn’t glumness, and their lightness isn’t flippancy. They descend bearing truth—but they don’t collapse under their own importance.

Some come with flaming swords.

Some with flickering laughter.

But all of them fly.

— The Accidental Initiate

***

“Not as it was, but as it meant.”

— Council Motto, adapted from memory

Leave a comment