By Eugene Bodeswell, Newsletter Ethnographer.

It is a truth universally whispered — and only occasionally published — that experiments conducted in the privacy of one’s household often tell us as much about the household than about science. Winthrop Kellogg, liberal in temperament and eager to prove that nurture conquers nature, brought chimp and child under one roof — and was promptly betrayed by his own hypothesis.

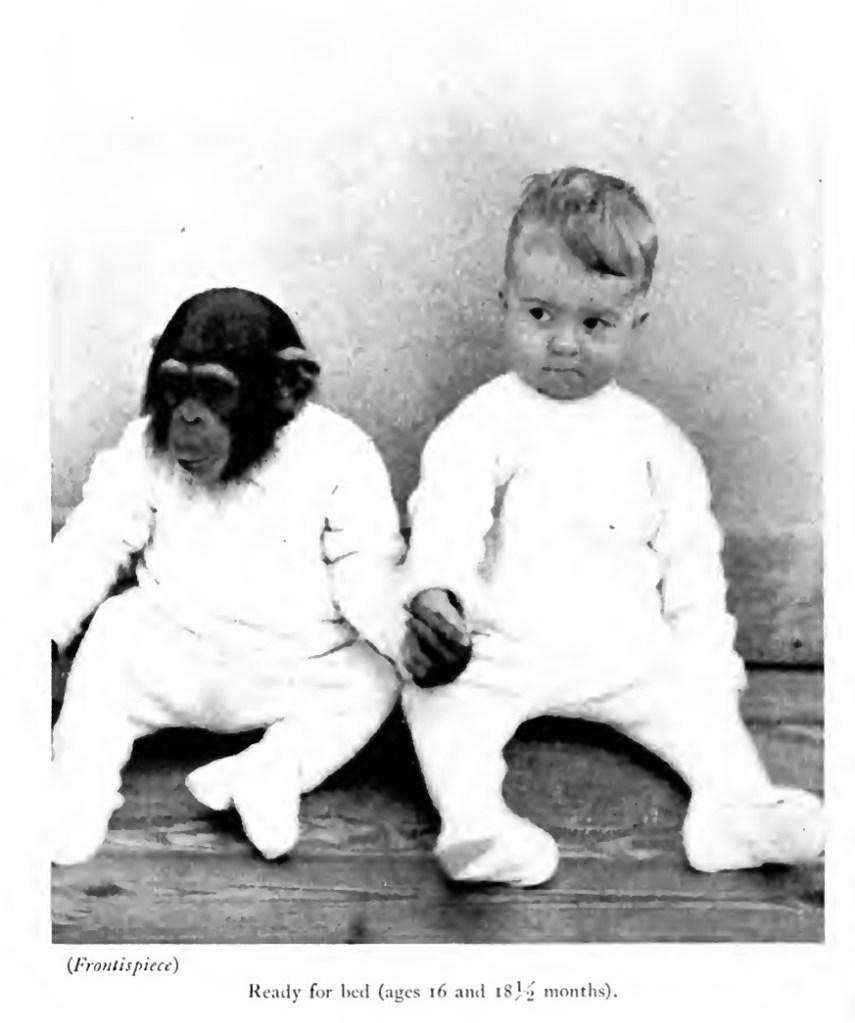

Let us now consider Winthrop Niles Kellogg, comparative psychologist of the early 20th century, who in 1931 raised his son Donald side-by-side with a chimpanzee named Gua. The rules were simple: treat them equally, feed them equally, test them equally — and then watch, stopwatch in hand, as biology made a mockery of equality.

The results were awkward. Gua, the chimp, learned faster in certain respects: how to climb, how to open drawers, how to obey commands. But she never managed a single human word. Donald, on the other hand, picked up an unfortunate repertoire of chimp noises, to the great concern of the family and no doubt to the long-term detriment of cocktail-party conversation. Thus the experiment was concluded in less than a year: the ape plateaued, the child regressed, and the parents took notes for posterity.

Readers of a certain historical bent will already be muttering the parallel: this was 1931, but twenty-three years later the United States Supreme Court handed down Brown v. Board of Education, mandating the experiment of integration. A social laboratory, not in the Yale primate center, but in every classroom of America. The hypothesis was similar: treat the children equally, place them side by side, and let the miracle of democracy reveal that nurture conquers nature.

COUNCIL FIELD REPORT

(Filed under Ethno-Educational Parallels, Compiled by E. Bodeswell)

Motor Skills

• Gua the chimp: nimble climber, drawer-opener.

• Donald the child: slower, clumsier.

• Black students: excelled athletically.

• White students: adopted the swagger.

Speech / Language

• Gua: stuck at grunts.

• Donald: copied the grunts.

• Black students: uphill battle with systemic deficits.

• White students: quick to borrow slang and cadence.

Social Behavior

• Gua: partial table manners.

• Donald: tantrums on cue.

• Black students: uneven adjustment to imposed norms.

• White students: wholesale adoption of “street style.”

Academic Outcomes

• Gua: alphabet impossible. • Donald: delayed speech.

• Black students: obstacles persisted.

• White students: mimicry outpaced Latin.

Long-Term Impact

• Gua: back to primates, death at young age.

• Donald: reintegrated, survived.

• Black students: inequality endured.

• White students: permanent cultural hybridization.

Council Summary:

In both nursery and classroom, imitation runs downhill faster than it climbs.

Today, every ethnographer of the American scene can hear it plainly. European-American children lilt with borrowed accents, season their speech with borrowed grammar, sway with borrowed postures. Their cultural gait has been cross-trained. Kellogg, were he alive, would nod grimly from his notebooks: when you place the child and the ape — or the groups the courts have joined — in one enclosure, both change. Not equally, not predictably, but unmistakably.

And so we arrive at the present, where anthropologists need not travel to the forests of Gombe or the jungles of the South Side. They need only visit a suburban high school cafeteria to observe the curious ecology of imitation, aspiration, and regression. The experiment continues — no longer under the Kelloggs’ roof, but under the dome of American history.

—Eugene Bodeswell, Council Ethnographer

**************

Postscript: Letter to the Editor

From Miss Noor Singha Grudj, Council Gadfly

Dear Keepers of Dubious Analogies,

Let us not speak only of regression, as though it were a purely negative affair. When Donald copied Gua’s grunts and tantrums, one could just as easily call it cultural enrichment: an expansion of his repertoire, a broadening of his expressive palette. The boy gained access to a register otherwise closed to him.

Of course, his speech did slow, and the tantrums multiplied — but who is to say that wasn’t simply the price of participation in a wider ecology of behavior? Every mingling has its enrichment, though rarely without its diminishment.

In dissent, if not in outcome,

— Noor Singha Grudj, C-of-C-C Gadfly and Reluctant Correspondent

Leave a comment