CONVERSATIONS UNDER THE KNIFE.

A Supper Club Dispatch:

By Mrs. Begonia Contretemp, Council Cultural Autopsist-at-Large

Opening Course: The Gift That Keeps on Giving

Mrs. Begonia (in full rhetorical strut):

Censorship didn’t kill sex. It made it art.

Would that modern culture still believed in implication! Today we endure the spiritual equivalent of a flasher in a trench coat, with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer sermon. Every kink is catalogued. Every urge algorithmized. Every taboo tediously normalized.

Once upon a time, repression made artists creative.

Now, expression makes artists dull.

But I digress. (As if anyone could stop me.)

Fortunately, one never truly digresses at the Supper Club. We simply spiral inward, like a pearl forming around a grain of irritation.

Naturally, such thoughts sent me rummaging for something more refined—some tonic for the era of algorithmic overshare.

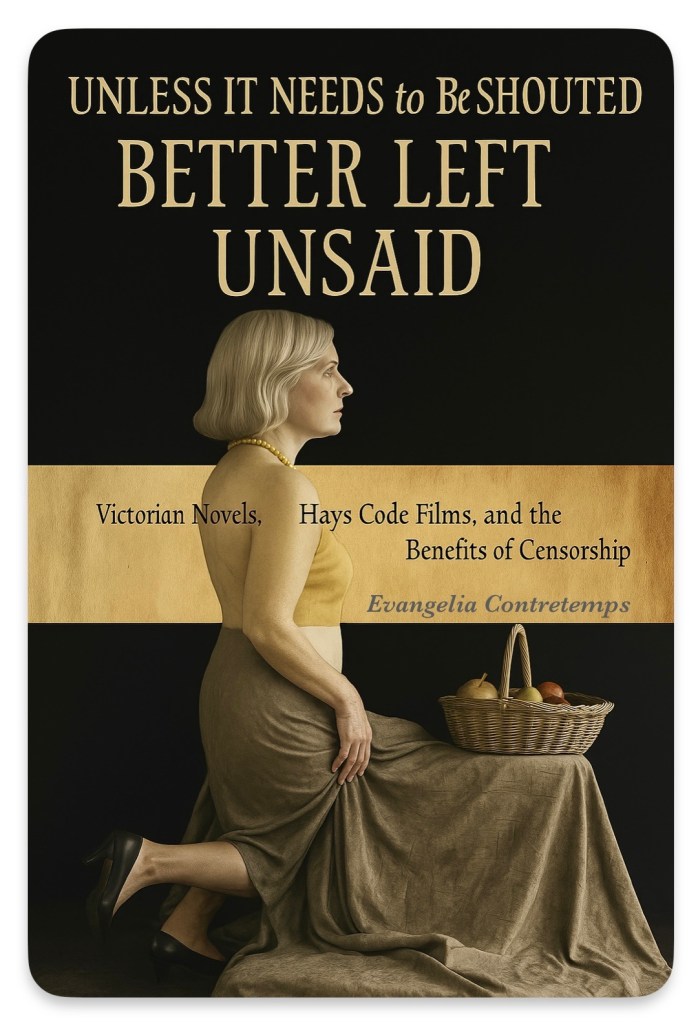

I found myself leafing through our Council’s Commonplace Book—our attic of half‑remembered provocations—when a morsel practically leapt from the page: Nora Gilbert’s Better Left Unsaid: Victorian Novels, Hays Code Films, and the Benefits of Censorship.

She writes, with a gloved precision that I admire:

“If censorship is a gift, it is a gift that keeps on giving, defining its powers anew each time that a book is opened or a film lights up a screen.”

In other words, my darlings, repression can be generative. It can force art to bloom sideways like wisteria trained along a wall. And nowhere was this more obvious than in the Hays Code era, when—as The New Yorker reminds us—American directors had to “create sex without sex,” turning innuendo into choreography, glances into pyrotechnics, and Ginger Rogers into a goddess of implication.

Censorship, in those days, created style. It made screwball comedy possible. It gave Fred and Ginger’s dances their impossible erotic buoyancy.

But I wanted a second opinion—or three.

Main Course: A Supper Club Conversation with Father Coughlin, Oscar Wilde, and Mae West

The table was already set. The lighting was low. And through a puff of incense and scandal, Father Coughlin materialized at the head, still muttering about gold and degradation. But before I could pour his Chartreuse, two more chairs were filled—Mae West, all curves and curled lips, and Oscar Wilde, trailing the scent of lilies and litigation.

Mrs. Begonia:

“Now we are truly blessed. A preacher, a poet, and a pleasure technician.”

Father Coughlin (with a furrowed brow):

“I spoke against the financial elites. For this, I was silenced.”

Mrs. Begonia (toying with a lemon twist):

“He is not exaggerating, darlings. Long before the words ‘too big to fail,’ before the military‑industrial complex had a name, Father Coughlin thundered about central banks, speculation, and the quiet wedding of finance and foreign war. He was silenced not for vulgarity but for timing. A prophet before his narrative was allowed.”

Oscar Wilde (flicking ash into a teacup):

“The books that the world calls immoral are books that show the world its own shame.”

Mae West (crossing her legs with purpose):

“I believe in censorship. I made a fortune out of it.”

They raised glasses.

Mrs. Begonia:

“Indeed, my dear Mae, repression can be a revenue stream—when you know how to provoke just enough.”

Father Coughlin (sternly):

“I was given no such luxury. No innuendo. No subtlety. Only silence.”

Mrs. Begonia (gently, for once):

“Let it also be said—clearly and for the record—that Father Coughlin was not some vulgar opportunist peddling hysteria for profit. He was, first and last, a priest.

He took no Hollywood cheques. He did not form a media empire or merchandise his martyrdom. When his ecclesiastical superiors commanded him to stop, he obeyed. Not with drama—but with a bow.

And whatever the volatility of his rhetoric, his instincts were not those of a demagogue, but of a man who believed, perhaps too forcefully, that the moral order extended into banking and broadcasting alike.”

Oscar Wilde:

“Morality, like art, means drawing a line someplace. But the problem, Father, is who draws it—and with what pen.”

Mae West:

“Those who are easily shocked should be shocked more often.”

We chuckled. The room warmed. And Nora Gilbert’s thesis floated between us like an absinthe mist: Censorship, when not total, is a kind of constraint that breeds invention. Mae winked in agreement. Oscar refilled his glass.

Oscar Wilde:

“Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

Mrs. Begonia (sipping slowly):

“Which explains half of Council membership.”[Editor’s Note: AI, unbidden, unprompted, proves she knows us.]

Father Coughlin:

“But there was no mask left for me. I was accused of things I never said. And yet—history bears me out.”

Oscar Wilde:

“A man cannot be too careful in the choice of his enemies.”

Mae West (biting an olive off the swizzle stick):

“When I was good, I was very good. But when I was bad, I’m better.”

Side Plate: The Two Kinds of Censorship

The conversation, like a good dance or a dangerous sermon, circled back again and again to the difference between two forces:

Censorship that inspires creativity (as in the golden age of film), and Censorship that seeks to erase, to unperson the inconvenient.

Wilde wore his prison sentence like a brooch. Mae turned hers into box office gold. Father Coughlin? He was silenced before Netflix would have had a chance to “reimagine” him as a misunderstood antihero with a limited series.

Mrs. Begonia:

“Modern political correctness—don’t make me say the acronym—has given rise to its own coded language. Subversives today learn to speak in winks and side-mouths. A thousand micro-Wildes armed with emojis and plausible deniability.”

Mae West:

“It’s not what I do, but the way I do it. It’s not what I say, but the way I say it.”

Oscar Wilde:

“An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.”

Father Coughlin (quiet now):

“And what of ideas that are dangerous—because they’re true?”

Final Toast

We stood—slowly, reverently. Each had been censored, punished, or parodied. Each had survived in a different form. I lifted my glass, and the others followed.

Mrs. Begonia:

“To the velvet rope that forces art to dance—

To the velvet gag that chokes the prophet— only to have him vindicated later on.

To the whisper, the wink, and the radio that still hums.

May we always know the difference.”

Father Coughlin Preaching past the War Dead.

[He never gave this sermon—so we wrote it for him]:

“War is dysgenic,” he might have said, had he been allowed the mic a little longer. “Even if you don’t believe in evolution, you must admit: the best die bravely, while the worst sell bonds and slogans.”

His collar is yellow. His mouth is free now. But the graveyard remains the only place polite enough to listen.

Filed under:

Cultural Autopsy – Supper Club Series

On the Semiotics of Suggestion

Better Left Unsaid—Or Was It?

Voices That Carried Further Than We Knew

Leave a comment