by Mrs. Begonia Contretemp, European Correspondent & Reluctant Passenger

There are few things in life as unnatural as voluntarily boarding a floating shopping mall with buffet lines. A cruise, I discovered, is a sort of capitalist monastery—except instead of silence and prayer, one vows endless piped-in music and the worship of the self in swimwear.

I told myself I was going for the German engineering. That was my alibi. Symphony of the Seas may fly a Bahamian flag and sell duty-free diamonds, but beneath its karaoke decks and frozen-drink machines beats a heart of Teutonic precision. Its propulsion system is by ABB—those sober Swiss-German technicians of torque—and its engines by MAN Energy Solutions of Augsburg, who have been keeping the industrial world spinning since before most of my fellow passengers could spell “Augsburg.” There’s something comforting about a vessel so overbuilt it could probably plow through the apocalypse while still offering line dancing on Deck Twelve. I went for the craftsmanship, I told myself, and stayed for the irony.

The engines were German, yes—but the passengers were unmistakably human.

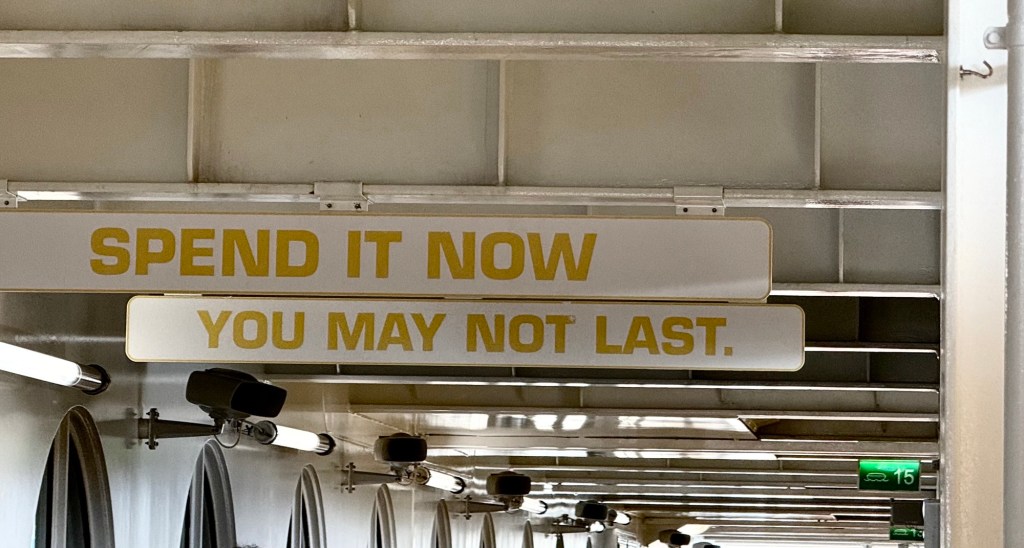

Everywhere you turn, there’s someone trying to sell you an upgrade: a better view, a better drink, a better version of yourself. There are lectures on “wellness,” boutiques peddling cubic zirconia spirituality, and stage shows where drag queens explain intersectionality between jazz hands. One can hardly cross the atrium without tripping over a motivational slogan or a man named Chad offering “exclusive discounts for your next voyage.” The effect is something between a duty-free store and a TED Talk given by Poseidon’s marketing intern.

At dinner one night, I turned to my traveling companion—who was heroically attempting to find sincerity in the wine list—and said, “I predict the next show will feature a plump negress on a high wire. They’ve already had the fire-eater, the interpretive dance troupe, and the diversity drum circle. High wire is the only circus left.” Sure enough, when we sat down in the theater and the curtain went up, there she was—suspended above us in sequins, wobbling over an audience of martini-holders who mistook suspense for enlightenment. All this in the off-Broadway version of the history of flight! I’ve never felt such vindicated despair. But I had nailed it as I slapped the shoulder of my companion in my triumph of prediction.

Another evening began with the cast belting out that 1970s anti-anthem WAR—“what is it good for?”—before launching into a sequence that somehow managed to combine Asian martial-arts poses, sword-fighting choreography, and a Haka temper tantrum by a troupe of hired Māoris. Was it a peace protest, a sales pitch for global unity, or simply the entertainment industry’s attempt to weaponize confusion? It was cultural appropriation as interpretive dance, and I applauded only because it meant it was over.

Like the proverbial man with a hammer who sees everything as a nail, certain modern writers seem to believe the world exists chiefly to be turned into a showtune. No tragedy is too grave, no historical wound too deep, that it cannot be resolved by a key change and a soft-shoe routine. The human condition, once explored in books or philosophy, is now belted out in chorus—complete with moral choreography and a mid-tempo lesson about inclusion. It’s the Broadway-industrial complex of feeling, and it has docked at sea.

Another evening promised Hairspray—the ship’s “inclusive reimagining,” which is cruise-code for a morality play in sequins. I lasted until intermission. The plot, as far as I could tell, involved a frumpy Jewish girl and her angelic Black allies outwitting a blonde stage mother and her peroxide progeny, thereby redeeming America through choreography. The audience wept, cheered, and congratulated itself for being on the right side of history while trapped in the middle of the ocean. I slipped out quietly, preferring the honest darkness of the deck to the sanctimony of the spotlight.

From my vantage point walking above the loungers, I began noticing what everyone else was reading. There was a quiet, almost desperate pattern: every other passenger seemed to have brought along a sea-themed book—The Old Man and the Sea, Life of Pi, Moby-Dick, even The Perfect Storm. It was as if they were all trying to intellectualize the very water beneath them, to prove they were voyagers of the mind rather than tourists with lanyards. I found it both touching and absurd—like watching people read about fire while roasting marshmallows.

Now to the buffet which is both miracle and menace. People who would faint at the idea of sharing an elevator with strangers now jostle elbow-to-elbow for scrambled eggs, calling it community. The crowd moves as one amorphous organism—sunburned, mildly drunk, yet pleasant—pulsing toward the next opportunity for “fun.” It’s the Tower of Babel, rebuilt on the high seas, and equipped with karaoke.

And yet—ah, reader—there is the balcony. The small private square of sanity, where civilization and salesmanship recede into mere background noise. There, over the ink-blue vastness, the air tastes like freedom and salt and the absence of slogans. The ocean doesn’t care about your loyalty program. It humbles you by simply continuing.

Truth be told, the only reason I agreed to this maritime circus at all was to please my companion, who’d been dreaming of “getting away from it all.” I should have known that “it all” would be waiting for us on Deck Nine with a drink package. Still, I can’t deny the pull of the ocean itself—the old blue hypnotist. Even from a lounge chair flanked by souvenir cups, its endless breathing can make one forget the absurdities above deck, at least for a moment.

So yes, I endured the crowds, the cheerfulness, the DEI-infused dance revues, and the relentless hawking of “experiences.” I did it for you. And I would do it again—for the five silent minutes at dawn when the horizon blushes and the sea reminds you what real depth looks like. There was, too, a small redemption in sound: a superb Latvian jazz guitarist of noble bearing who played in one of the quieter lounges, his fingers translating melancholy into grace while the rest of the ship shouted over dessert. He never smiled, which I found reassuring. For those few sets each evening, it felt as though civilization had not entirely gone overboard.

In the end, I must admit I boarded reluctantly and only to please my companion. They wanted a voyage, I wanted plausible deniability. And yet, somewhere between the buffet stampedes and the Latvian guitarist, I discovered that even reluctant travelers are capable of gratitude. The ship may have been a floating shopping mall, but it was also a lesson in surrender—to the sea, to another’s wish, and to the comic inevitability of discomfort. If love is measured in sacrifices, I suppose this one will do.

By the time we glided back into New York Harbor, I was prepared to loathe everything on sight. But there she was—Liberty herself, still holding the torch against a skyline that looked like the afterlife of Europe’s ambitions. I wanted to sneer at the glass towers, those monuments to appetite and algorithm, yet part of me marveled at the sheer audacity of it all. Say what you will about modernity’s vulgarity—no other civilization could have built such magnificence while apologizing for it at the same time.

Leave a comment