—How the Pennsylvania Dietsche Turned Humor Into Heritage.

BOOK NOTES

—A notice of upcoming titles from Coelacanth Press and other highly recommended discoveries from our forays into the cultural thickets of America. This one was unearthed by our own Rootless Metropolitan on a recent trip.

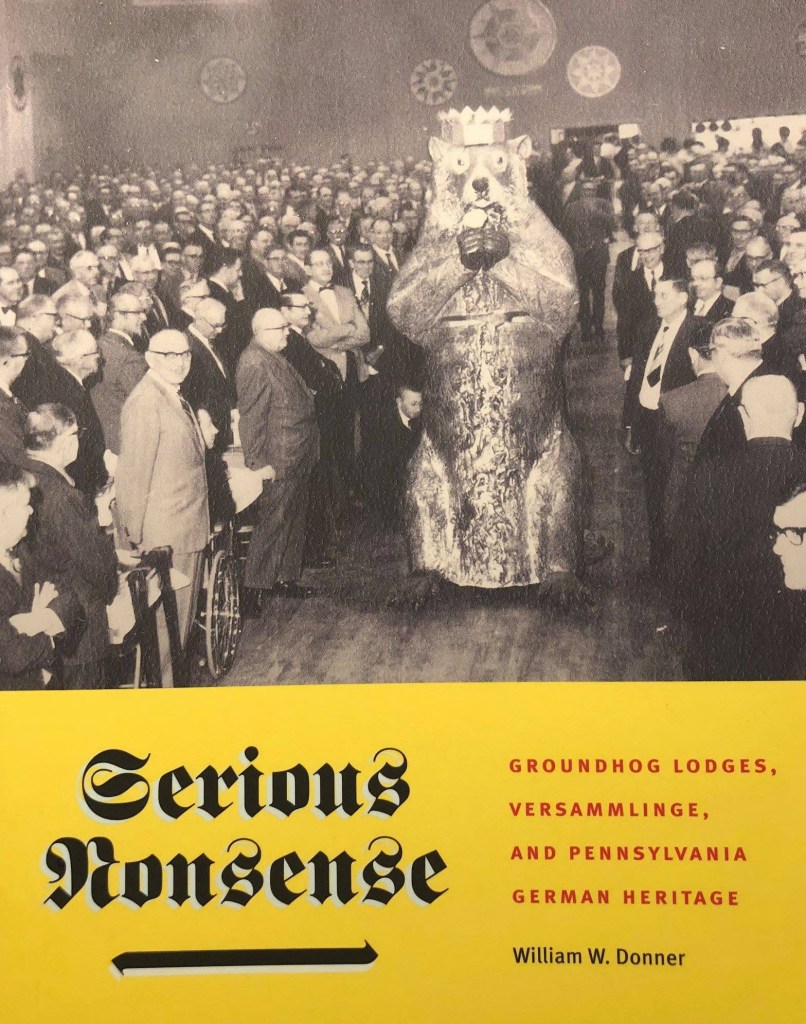

SERIOUS NONSENSE

—By William W. Donner

Dear God in heaven, let us Deitsche (Pennsylvania Germans) be what we are.

—the motto on the Pennsylvania German flag

As a Rootless Metropolitan I have a talent for wandering into a bookstore and coming out not with a book, but with the book I didn’t know I needed—something that smirks from the shelf as if it were waiting for me. That’s how Serious Nonsense made its way into Council circulation.

You’ve heard of the Racoon Lodge from Brothers Norton and Ralph of The Honeymooners, and of course everyone knows the annual rites of Groundhog Day. But did you know that all this American mischief owes something to our own C-of-C-C cousins among the Pennsylvania German settlers?

The Dietsche language—a lively, earthy descendant of southwest German dialects—was spoken informally among these pioneer farmers from the moment they set foot in the New World. Compared to Standard or High German, Dietsche delights in expressive twists of sound. A favorite example offered by its speakers is the emphatic, rounded “schtubbich” (meaning stubborn, thick-headed, endearingly immovable). High German writes essays; Dietsche elbows you and laughs.

This expressive instinct turned out to be a cultural survival strategy. After WWI, when public sentiment ran suspiciously cold toward anything German, the Pennsylvania Deutsch responded with a stroke of folkloric genius: they formed Groundhog Lodges, fraternal societies where only Dietsche could be spoken. Anyone slipping into English received a small fine—half penalty, half punchline.

The lodges served a double purpose:

Preserve the heritage. Reassure the WASPs.

Patriotic songs were sung. The Pledge of Allegiance was performed with gusto. And all of it revolved around the most unlikely totem animal—the groundhog—whose Old World cousins had long been considered shrewd weather prophets. The American woodchuck, with its comic seriousness, fit the bill perfectly.

The rites borrowed the absurd theatricality of Masonic ceremony: robes, mock pageantry, secret passwords, and a ritual solemnity frequently interrupted by laughter. The result was cultural diplomacy in the form of high camp—exactly the sort of “serious nonsense” that the modern C-of-C-C knows in its bones.

German-Americans felt real pressure in the post-1918 years. In New Jersey, the old settlement of German Valley quietly rebranded itself as the more neutral Long Valley—though the 18th-century fieldstone houses still stand like granite footnotes reminding everyone who built the place.

And right down the road from where this is written lies the site of the scarcely remembered Battle of the Short Hills. In 1777, Cornwallis attempted to lure Washington into a European-style open-field battle by advancing two columns from Perth Amboy and New Brunswick. A detachment of Pennsylvania Germans stalled one of these columns near today’s Oak Tree and Inman Avenues. Remarkably, the men they held off were Hessian Jägers—German versus German on American soil. According to historian Robert Mayers in Revolutionary New Jersey, this delay allowed Washington to retreat safely to the Middlebrook hills, in a region now partly quarried away by the St. Evola operation—no close relation, though the Council takes note of the synchronicity.

—most of the Americans in the second encounter had not chosen it at all, but were drafted into the fight.

Episodes like this reveal how deeply the Pennsylvania Germans were woven into the American fabric. They never doubted their claim to the New World, and history justified their confidence.

Finding Donner’s book in the Otto Bookstore of Williamsport—founded 1841 and still standing like a sentinel of regional memory—felt like uncovering a long-lost branch of the Council family tree. We thought our own high camp was a recent innovation, but it seems Americans have been perfecting that mode since long before we arrived. Consider the outrageous costumes at the Boston Tea Party or the “Calico Indian” antics of the Anti-Rent War in upstate New York. For that matter, consider the memetic tricksters who helped launch Donald Trump in 2016. The lineage is unmistakable: American revolt has always worn a grin.

The versammlinge (meetings) of the Groundhog Lodges were gatherings of ordinary Lutheran farmers—the “Church Germans,” to distinguish them from Amish and Mennonite separatists. Their humor wasn’t escapism; it was a tactical affirmation of belonging. One suspects there’s a lesson there for our own times, when humor has again become a political tool, a binding ritual, and a cultural refuge.

The lodges still exist, but the fragmentation of globalized entertainment and digital distraction has thinned the ranks. Heritage takes attention, and attention is the rarest resource in the world. Yet the old impulse remains: the common folk organizing, on their own terms, to keep ancestral ways alive through collective joy.

From Serious Nonsense:

“Linguists often cite an adage, ‘a language is a dialect with an army and navy’; the distinction between language and dialect rests more on politics than on linguistic reality. Pennsylvania Germans do not have an army or navy—so perhaps they have a ‘dialect.’ In my view, however, they possess a distinctive language that descended from the dialects of southwest Germany, then evolved into its present form in the United States, developing its own literature and cultural contexts.”

—William W. Donner, Serious Nonsense, p. 17

Leave a comment