Providence Notes, Recovered

by The Accidental Initiate

[Editor’s Note — John St. Evola

The Accidental Initiate went to Providence for reasons that appeared sensible at the time and grew less so with every mile. The newsletter had sent him to report on the recent murder at Brown University.

This is often how his trips begin. Providence had that effect: a city where history lingers just long enough to make you wonder whether it is merely remembered—or quietly remembering you in return.

Not far from there, in New London, once lay the USS Providence—a nuclear submarine bearing the city’s name, prowling depths no one sees, carrying powers best left hypothetical. One cannot help pausing over the coincidence. How could Lovecraft, writing decades earlier, have known that something so uncannily analogous to his abyssal god—the dreaming thing he later named Cthulhu, silent, submerged, world-ending by design—would one day be stationed just down the coast? He did not predict it, of course. He intuited the shape of it. He understood that modern power would not announce itself from the mountaintop, but would instead wait below the surface, patient and absolute.

Lovecraft placed his gods underwater not merely because the sea is mysterious, but because it is patient. Submarines share that temperament. They wait. They listen. They possess the peculiar authority of things that do not need to be seen in order to decide the fate of what lies above them.

It seemed inevitable, then, that the Accidental Initiate—wandering College Hill with Lovecraft on the brain—would begin to feel that familiar pressure one senses before descending: the intuition that panic, like sonar, sometimes returns a signal not meant for the conscious mind at all. What follows is not an argument, nor a diagnosis, but a record left intact—filed before the echo could fully resolve, and before anyone thought to ask what, exactly, had answered back.”]

“I am Providence,” his stone declares—once a statement of origin, now something closer to a question about what Providence itself has become.

The Accidental Initiate:

In the days following the shooting at Brown University, the authorities held briefings whose chief accomplishment was multiplication. And the Chief explaining everything seemed to be the type who once had a problem with multiplication tables. Each appearance produced more motives, more contexts, more cautions about context. Rumors of Musselman shouts of Alley-boo Snack Bar! at the scene of murder were murmured. Not exactly a call to lunch.

Nothing was denied; nothing was affirmed. Online profiles were scrubbed. Understanding was urged to wait. Meanwhile, the city was left alone with its questions.

What troubled me was not any single explanation, but the sense that too many motives, ambitions, and cultural references had been mashed together without hierarchy or coherence, until nothing quite explained anything. Except maybe grievances imported from exotic lands. The mind kept reaching for a pattern and finding only overlap.

I walked College Hill assuming—without ever having tested the assumption—that Providence still knew what it was doing. The buildings stood with that old collegiate confidence, brick piled upon brick as if centuries themselves formed a kind of protection. One grows careless around such architecture.

What produced the unease was not any single motive, but the comic excess of them: ambition colliding with grievance, ideology elbowing pathology, personal despair borrowing slogans it barely understood. Too many stories occupying the same square foot of pavement.

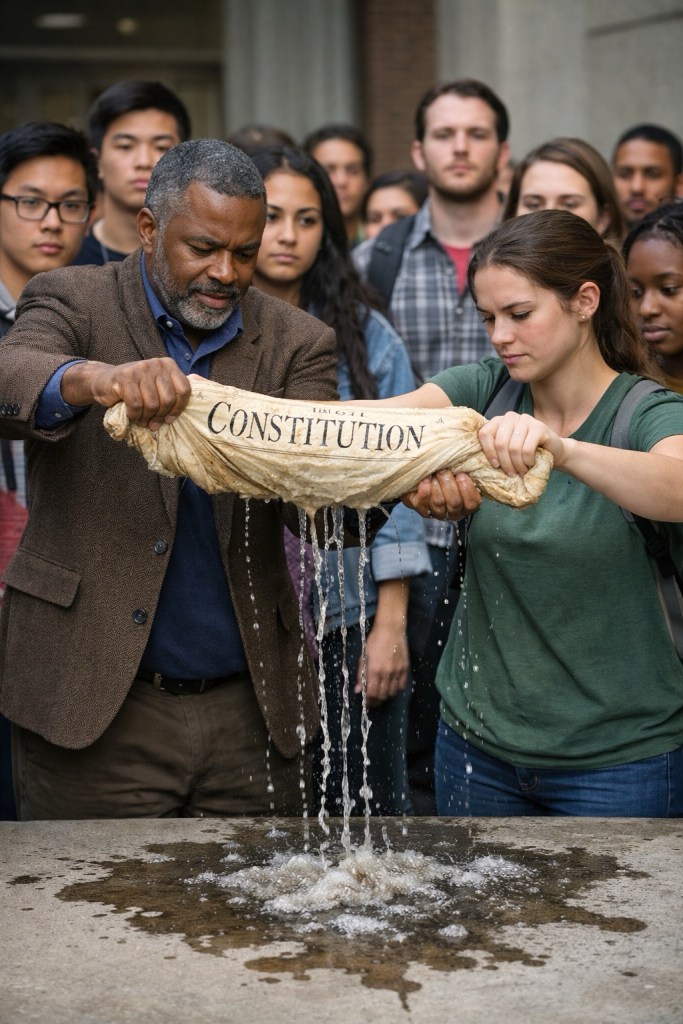

In The Horror at Red Hook, Robert Suydam becomes enmeshed in shadowy rites that leave him disturbingly animated — a man whose vitality seems borrowed from arcane ceremony rather than genuine life, and whose strange reappearance amid collapsing basements and cultic graffiti haunts the detective Malone’s memory. One could not help noticing a modern echo: a campus culture expending immense ceremonial energy to animate exhausted doctrines, formulas repeated with a diversity poobah’s meticulous care in the hope that, if performed correctly, they might yet stir back to life the faded promises of America’s founding. In both cases, the air grows thick with ritual seriousness and diminishing returns — the uneasy sense that motion has replaced meaning, and observance now stands in for life.

Lovecraft feared, even as he recoiled from it, that his panic would also carry the weight of prophecy. He caught something true: the moment when the street stops explaining itself. Monsters, with overlapping meanings stacked without order, signals crossing like bad radio frequencies, a city speaking in too many tongues at once and therefore saying nothing at all.

The dark joke, I realized, was that Providence had spent generations congratulating itself on not being Red Hook—only to discover that Red Hook is not a place you keep out. It is a condition you drift into when no one remembers which rules were load-bearing.

Lovecraft fled Brooklyn and blamed the people. We remain, issuing statements, which may be the more advanced superstition.

I left the hill amused in the bleakest possible way: the horror had arrived wearing credentials, footnotes, and a perfectly serious tone—and still no one could quite say who was supposed to stop it.

**************

After Shouts

— by Vito Haeckeler,

C-of-C-C man-on-the-street (Providence Bureau)

There is a theory circulating that Providence sits closer than it ought to the Lovecraftian edge. I’d argue the opposite. Nearly one-in-five Rhode Islanders claims Italian ancestry—one of the highest concentrations in the country—and that matters more than anyone admits. A city tethered to broccoli rabe and sausage, to stuffed artichokes, to braciole that’s been simmering since morning, is not easily dragged into the abyss. Federal Hill alone exerts a gravitational pull strong enough to keep most ancient horrors at bay.

I should disclose again that my mother was Italian, which makes me only half qualified to make this argument. The other half of me is German, which explains why I sometimes feel the pull of the Gothic—the fog, the brooding, the shouting into the void, the sense that something unspeakable might be lurking just offstage. But the Italian side intervenes. It insists on lunch. It asks whether anyone’s eaten yet. It reminds me that no cosmic dread survives contact with a table set properly. Providence remains upright not by theology or theory, but by dinner.

Leave a comment