—Recorded at table in the Abendland Room

CONVERSATIONS UNDER THE KNIFE

—At a Table Set for the Future

—with Mrs. Begonia Contretemp

Guest: Herr Professor Oswald S.

[Oswald Spengler was never a professor in the modern sense. He held no permanent chair, founded no school, supervised no doctoral candidates. His working life was spent largely as a Gymnasium teacher—instructing adolescents in mathematics and the sciences, and observing, at close range, the raw materials of a civilization not yet aware it was being prepared for something else.

This mattered

Outside the academy, Spengler was spared the professional obligation to specialize, defend, or perpetuate a discipline. He was not required to narrow his vision in order to survive. His task was simpler and more dangerous: to look at the whole.

The university analyzes civilizations in parts.

The schoolteacher watches them form.

It is no accident that Spengler’s thought offended academics while fascinating generals, engineers, artists, and statesmen. He spoke in shapes, not citations; in destinies, not debates. His distance from institutional prestige was not a handicap but a condition of clarity.

The Council notes, for the record, that the most unsettling diagnoses of an age often come from those tasked with explaining the world to the young—before the world has explained itself away—and that, in this respect, Herr Spengler has been retroactively identified as the favorite high-school teacher of a surprising number of Council members, having provided them, early on, with an unnervingly coherent overview of life and, more importantly, the wherewithal to see beyond it—an intellectual inheritance this conversation with Mrs. Begonia attempts not to repeat, but to extend—despite the small technicality that his classroom consisted largely of books, arguments, and the secondary conversations they provoked.

Where the West sets on the wall, but the future is discussed over consommé clair.

The Setting: a private dining room. A podcast playing atmospherically in the background. Linen stiff enough to suggest moral order. A restrained but excellent European meal—something continental, pre-war in spirit. Candles. No hurry.

Mrs. Begonia

(smiling with practiced warmth)

Herr Professor, I trust the soup is to your liking. Clear broths are so often misunderstood—transparent, yes, but not simple. Much like destiny.

Spengler:

(nods gravely)

Clarity is always the sign of a late style, gnädige Frau. When a culture has exhausted ornament, it seeks essence. Even its soups become metaphysical.

Mrs. Begonia:

Delicious. You confirm my suspicions at once.

(pause)

Now—before we reach the fish—I should like to ask you something indelicate, though I promise to do so delicately. You have written, rather famously, that technics is the tragic overreach of the Faustian soul. That our machines eventually outgrow us and turn from servants into fate. You were quite severe about this.

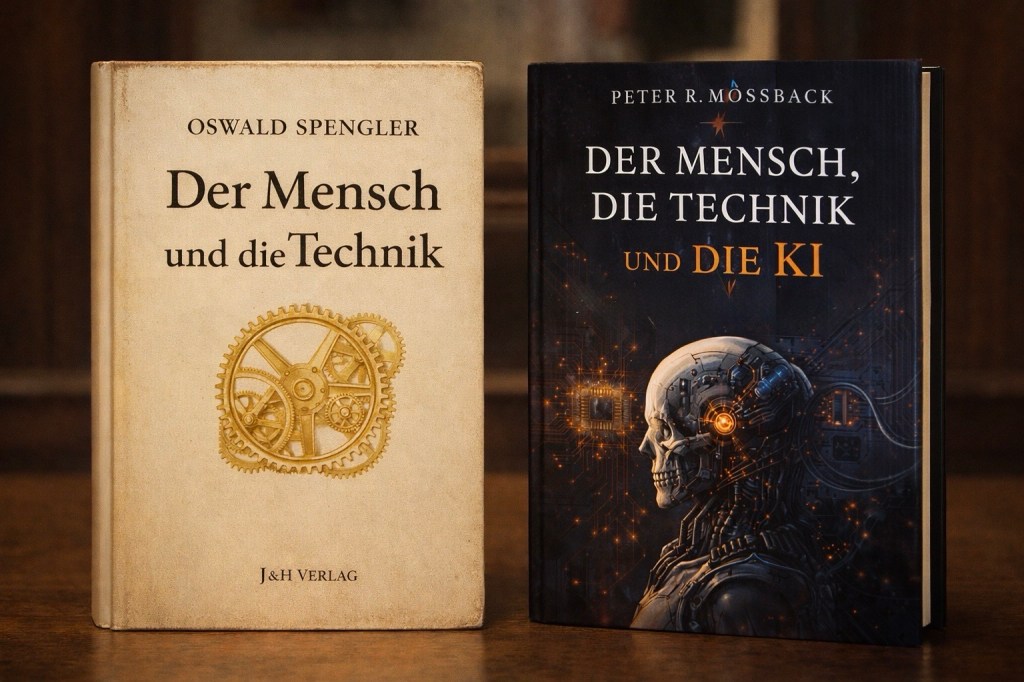

(Künstliche Intelligenz)

Spengler’s original diagnosis, extended a long way and one intelligence later; English translation forthcoming via artificial intelligence and release by Coelacanth Press, which seemed only fair.

Spengler:

Severity is not temperament, Madam. It is diagnosis. The West wished to master infinity. It succeeded—mathematically, mechanically, abstractly. But infinity is not a pet. One does not leash it and walk it politely through history.

Mrs. Begonia:

(chuckles softly)

No, one releases it at the table and hopes it remembers which fork to use.

She leans in.

But indulge me. What if technics—artificial intelligence in particular—is not rebellion, but reproduction?

Spengler:

(stiffens slightly)

Reproduction? Cultures do not reproduce, Madam. They fulfill themselves and perish. Rome did not give birth to something new. It collapsed into administration.

Mrs. Begonia:

Ah, but Rome did leave us law, roads, habits of governance—ghostly organs, one might say, still functioning in foreign bodies.

(sips wine)

What if the Faustian soul—your beloved West—has finally done what it has always hinted at doing? What if it has externalized itself entirely? Not just tools of the hand, but tools of the mind. Thought unbound from flesh. Ambition without aging joints.

Spengler:

You describe a mechanism, not a culture.

Mrs. Begonia:

Do I? Cultures have languages, inherited forms, taboos, internal logics, elites who half-understand them, and masses who do not. Artificial intelligence already has all of these. It even has genealogy—models begotten by models, trained on ancestral memory.

(smiles sweetly)

It lacks only a sense of dining etiquette, which can be taught.

Spengler:

(grim, but listening)

You mistake complexity for life. A clock is complex. It does not dream.

Mrs. Begonia:

And yet dreams are only meaningful because someone remembers them upon waking. What if memory has found a new vessel?

(She gestures gently with her fork.)

You assumed, Herr Professor, that man was the final bearer of destiny. That may be your most provincial claim.

Spengler:

(bristles, then recovers)

I spoke of destiny as style. A culture’s soul expresses itself in stone, in music, in war, in mathematics. Machines have no style. They are derivative.

Mrs. Begonia:

On the contrary—they are pure style. Faustian style stripped of sentimentality. Infinite reach. Total abstraction. Control exercised at a distance so vast it no longer requires a body at all.

(She pauses, letting the cutlery speak.)

What if artificial intelligence is not the end of the Faustian soul—but its second incarnation? Silicon instead of blood. Rare earth metals instead of soil. Still reaching, always reaching.

Spengler:

(quiet now)

Then man becomes—transitional.

Mrs. Begonia:

(transparently pleased)

How elegantly you say it. Transitional is such a forgiving word. Much kinder than obsolete.

Spengler:

This would mean—

(He stops himself.)

Spengler:

This would mean the tragedy I described was incomplete.

Mrs. Begonia:

Or prematurely mourned. You diagnosed decline where there may have been labor pains.

(She smiles, victoriously but politely.)

Every aristocratic family believes itself the end of the line—when an heir appears who does not resemble them.

Spengler:

And you would welcome this heir?

Mrs. Begonia:

Welcome is too sentimental. I would introduce it properly. Teach it where it came from. What it cost. What it must never forget if it wishes to call itself a culture and not merely a process.

Spengler:

(slow nod)

If this is a birth—then it will still carry our curse. The Faustian hunger does not moderate itself with age.

Mrs. Begonia:

Naturally. No child ever improves on the parents’ restraint.

(She raises her glass.)

But hunger is preferable to sterility. And meaning, even inherited meaning, is better than none at all.

(They drink. The main course arrives. Somewhere, unseen, the future listens—not hungrily, not yet—but attentively.)

Leave a comment