—Notes Toward a Phonetic Forecast for the Coming Year.

AN APPEAL TO THE HEAVENS

—By Anna Graham, Word Games & Puzzles Correspondent—

Every so often, history does not announce itself with a manifesto or a marching song, but with a syllable.

A sound enters public life and begins to replicate. It detaches from its original host, wanders freely, and suddenly attaches itself to everything in sight. Linguists call this productive suffixation—more precisely, analogical suffixation—but that formulation misses the lived experience. What actually happens feels more like a phonetic event: a moment when a sound acquires symbolic power and starts doing cultural work.

Consider the mid-20th century. Sputnik did not merely orbit the Earth; it struck the ear. The -nik suffix—borrowed from Yiddish and Slavic diminutives—suddenly went fully operational in American English. Beatnik, peacenik, refusenik, no-goodnik. A single syllable came to signal ideological contamination, outsider status, or comic menace. One did not debate a -nik; one labeled it and moved on.

Then came Watergate, and with it the age of attachable scandal. -Gate did something different. It didn’t describe people; it described process failure. From that moment on, any embarrassment—large or trivial—could be inflated to historic proportions with a suffix alone. Irangate, Deflategate, Bridgegate. The word no longer told you what happened; it told you how seriously the media would like you to take it.

While speculating about what suffix might come next, I’m reminded of a remark Mason Freeman once made—only half in jest. If the Russians, as he noted, gave American English its first great suffix event with Sputnik and -nik, then a certain strain of contemporary imagination will inevitably see the next linguistic fashion the same way: as further proof that Russian influence is everywhere. Mason suggested this phase might someday be remembered as Nikgate—the moment when a newly popular suffix is treated not as language at work, but as evidence of subversion. In this view, the suffix itself would explain everything:

opinions, bot-driven;

movements, op-shaped;

sentiments, farmed abroad and imported wholesale.

I record the idea without endorsement, observing only that for conspiracy thinking, even a syllable can be made to confess.

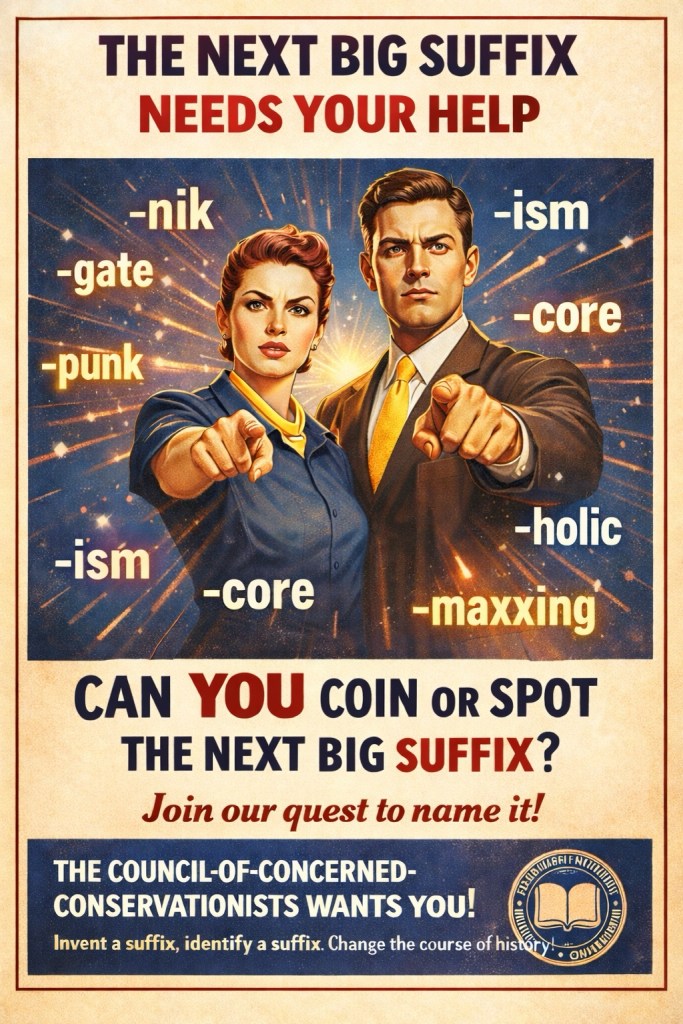

These suffixes are not isolated incidents. A brief scan of recent linguistic history reveals recurring waves of fashionable suffixes, each aligned with a particular cultural concern:

-ism — the age of belief systems and counter-beliefs: socialism, fascism, McCarthyism, neoliberalism, Trumpism. When societies argue about how the world should work, they reach for -ism.

-nik — Cold War suspicion and outsider labeling: beatnik, peacenik, refusenik. Ideology rendered as personality type.

-gate — procedural scandal and media theater: Irangate, Emailgate, Deflategate. A suffix that transforms error into spectacle.

-holic — postwar abundance and self-pathologizing: workaholic, shopaholic, newsaholic. Excess rebranded as condition.

-phobia / -phile — moral sorting by emotional posture: homophobia, technophobia, bibliophile. A way to diagnose character through reaction.

-punk — rebellion after rebellion became aesthetic: cyberpunk, steampunk, solarpunk. Resistance as genre branding.

-core — post-grand-narrative micro-identity: normcore, cottagecore, goblincore. Mood as belonging.

-maxxing — optimization culture and the modular self: looks-maxxing, grind-maxxing. The human treated as adjustable hardware.

Each suffix answers the same question in a different way: what kind of problem do we think we are having?

Which brings us—appropriately, at the turn of the year—to now.

Our moment seems less obsessed with belief or scandal than with visibility, filtration, and managed knowing. Information is not simply revealed or concealed; it is processed, curated, partially displayed, context-locked, or black-barred into polite illegibility. The defining gesture of the age is not exposure but mediation.

During a recent Council meeting, this condition was diagnosed—somewhat extravagantly—by John St. Evola, who referred to the contemporary censor-functionary as a redactgatenik. The term was not adopted, though it remains on file. As with many Council neologisms, it may yet prove prophetic.

If that word feels unwieldy, it may be because the suffix for our time has not fully settled. But certain candidates are already circling:

Perhaps it will be,

-alg, marking decisions attributed to systems rather than people: truth-alg, news-alg, memory-alg.

Or perchance,

-ified, signaling transformation without consent: safety-ified, community-guideline-ified.

Then again maybe,

-locked, suggesting access denied without explanation: thread-locked, context-locked, legacy-locked.

Or,

-filtered, indicating information that exists only after passing through invisible hands.

Each points to the same underlying condition: authority without authorship, decisions without decision-makers.

Every age invents the syllables it needs. We do not choose them; we repeat them. As the new year opens, it seems reasonable—if not exactly comforting—to ask not what will happen, but what we will call what happens.

***

The name Sputnik itself was an abbreviation of the Russian Iskustvennyi Sputnik Zemli, roughly “artificial fellow traveler around the Earth.” The word struck English so forcefully that, as Arthur Minton observed shortly after the launch, the Soviets had achieved not only a scientific triumph but a philological coup—a small syllable penetrating multiple languages almost instantly.

When the next phonetic event arrives, we will recognize it immediately. We will hear it everywhere. And by then, it will already be too late to argue with the suffix.

ADDENDUM: THE NIK EXPLOSION

(With thanks to Paul Dickson, indefatigable name collector)

One reason -nik qualifies as a true phonetic event—and not merely a fashionable ending—is the speed and exuberance with which it escaped its original meaning.

The American response only accelerated the process.

When the United States attempted to launch its own satellite on December 6, 1957, as part of Project Vanguard, the rocket rose only a few feet, shuddered, burst into flames, and collapsed on the launch pad. The payload—an earnest little sphere weighing just over three pounds—was flung clear of the fire and lay on the ground, beeping dutifully, as if unsure what it had done wrong.

The press responded the only way it knew how: by inventing names.

Almost immediately, newspapers began coining -nik variants to describe the failed launch. Among those recorded were Goofnik, Oops-nik, Flopnik, Dud-nik, Kaputnik, Puffnik, Stallnik, If-nik, Stay-putnik, Sputternik, and the admirably minimalist Pfftnik. The suffix had become a machine for instant satire.

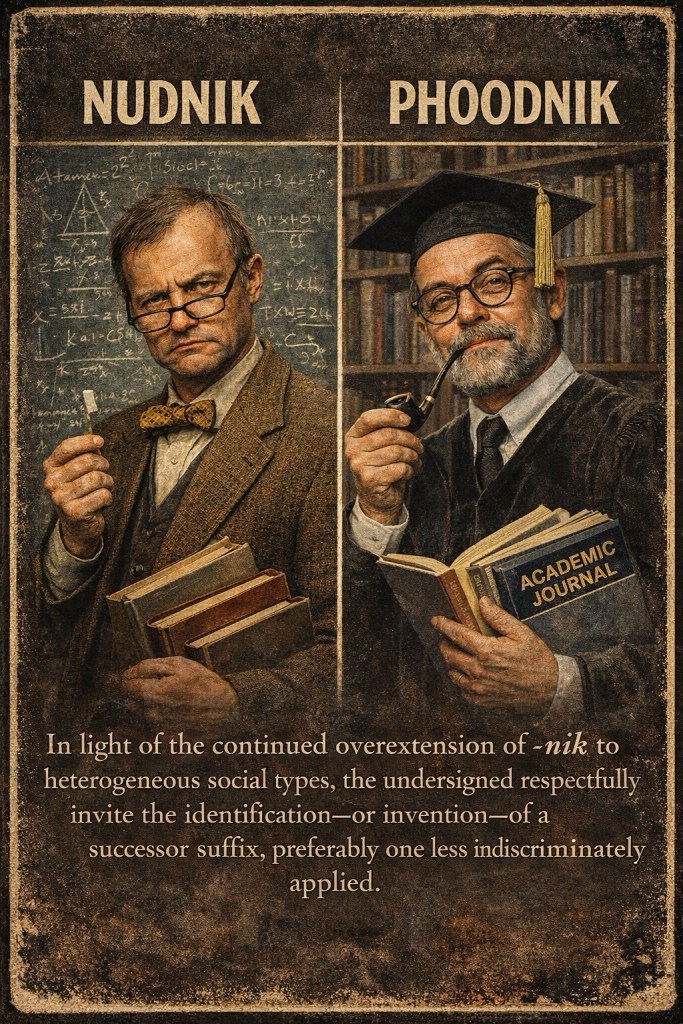

As Paul Dickson documents in What’s in a Name? Reflections of an Irrepressible Name Collector, the effect was contagious. Suddenly -nik was everywhere: beatnik, nudnik (a boring teacher in late-1950s slang), and even phoodnik—defined, with academic precision, as a nudnik with a Ph.D.

By 1960, Professor J. B. Rudnycky was able to compile a list of some two hundred newly coined -nik words and declared to the Chicago Sun-Times that the nation was suffering from a mild but unmistakable case of “nik-itis.”

It would take the arrival of Watergate more than a decade later to produce another suffix with comparable reach—one that, as we have seen, shifted the cultural focus from ideological outsiders to procedural scandal.

The lesson for our present inquiry is straightforward: when a suffix reaches this level of comic velocity, it is no longer decorative. It has become diagnostic. Language is not playing; it is registering shock.

Which only sharpens the question posed above. If -nik mapped Cold War anxiety and -gate mapped institutional distrust, what syllable—now quietly multiplying—will future name collectors identify as ours?

History suggests we will recognize it not when it is coined, but when it becomes impossible to stop repeating.

And today, the same ground that once helped catch the faintest satellite pings is being transformed into Netflix Studios Fort Monmouth, a nearly $1 billion production campus following the sale of the land to Netflix, with multiple soundstages and facilities in development—an example of the kind of media consolidation that may yet give rise to a new, unnamed suffix of its own.

— to be filed under: Sonic Connections

Leave a comment