BOOK NOTES

—Entered into the record by Coelacanth Press, the Publishing Imprint of the C-of-C-C Newsletter

The discovery was not intentional.

While cataloging volumes recovered from what I, the Council Sub-Sub-Librarian has come to call the submerged library—a phrase meant descriptively, not metaphorically—we noticed a repetition that did not announce itself until it had already occurred several times.

No fewer than twelve titles in our editor’s personal collection begin with the words “THE LAST—”.

This was not a curatorial decision. Our editor did not set out to assemble a thematic shelf, nor is he the sort of reader whose habits are governed by obsessive symmetry. He is not that autistic a collector. In fact, we have not yet informed him of the pattern, although given his proximity to this newsletter, it is entirely possible he is discovering it at the same time you are.

What the editor has revealed over the years—usually unintentionally—is that his reading life functioned as a kind of alternative residency within time. Of sports, he recalls little beyond the fact that Y. A. Tittle once quarterbacked the New York Giants in the early 1960s. Of television, only fragments remain: Get Smart, Flipper, perhaps Taxi. After that, the signal fades. Most of his spare hours were spent with his face in a book.

Some would call this escapism. We disagree.

Books, and the ideas and descriptions they contain, are as much a part of the real world as what is more commonly referred to as the here-and-now or the it-is-what-it-is of reality. They exist in the same ontological space, though with fewer interruptions. Books are not as messy as real life. In that sense, they are an improvement.

Turning one’s back on popular culture is not always a retreat. Sometimes it is simply a refusal to be hurried.

Still, there is something peculiar about owning twelve books whose titles begin with “The Last—”. Even if the choice was unconscious, the recurrence says something—about the age in which these books were written, and perhaps about the psychic weather in which they were read.

A cursory internet search reveals that Goodreads alone lists 239 books beginning with the same phrase. This raises a question that extends beyond content. What does it mean that our era so readily markets its stories as endings?

Book titles are designed to seize attention. They do not always describe what lies within, but they do reveal something about what a reader is being primed to feel before the first page is turned. “The Last” does a great deal of work in advance. It promises urgency without obligation, gravity without participation. You are not required to save what is vanishing. You are only asked to witness it.

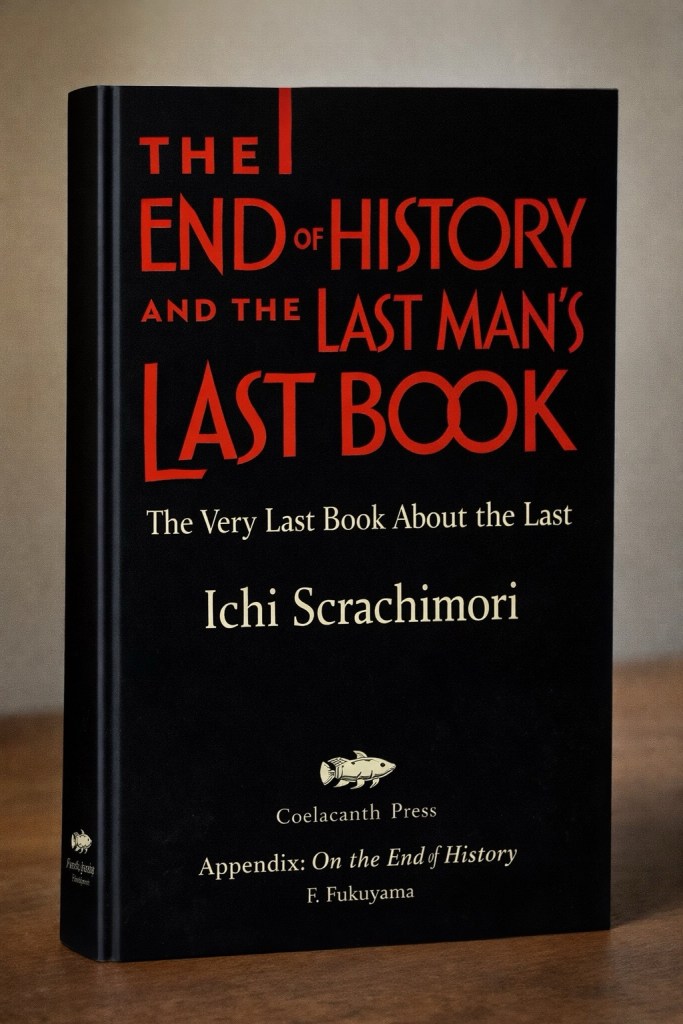

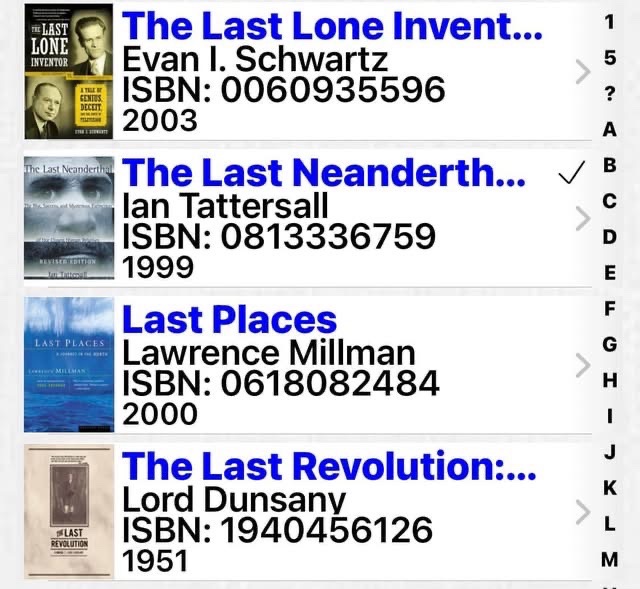

Our editor’s shelf includes, among others:

The dates range from the mid-20th century to the turn of the millennium, with one notable outlier from 1951 that reads, in retrospect, like an early prototype—an intimation before the habit fully set in.

What is striking is that these are not apocalyptic texts. They are elegiac. The “last” in question is rarely a bang. It is a thinning. An attrition. A quiet handover no one quite remembers agreeing to.

Beyond the books actually owned lies a much larger, unpurchased constellation:

The Last Man

The Last of the Mohicans

The Last Emperor

The Last Tycoon

The Last Unicorn

The Last Picture Show

The Last Lecture

The Last Thing He Told Me

Civilizations, species, empires, technologies, lectures, relationships—nothing appears immune from being framed as final. The phrase stretches easily. Too easily. It attaches itself wherever loss can be made legible, portable, and saleable.

Once this pattern was noticed, however, it did not remain alone.

As the eye adjusted, a second editorial formation emerged nearby—equally common, equally unintentional, and perhaps more revealing still. Scattered throughout the same shelves, and multiplying rapidly in the wider culture, are titles that follow a different but closely related formula:

“How X Changed the World.”

Or some close variation thereof.

Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World, Mark Kurlansky

The Machine That Changed the World, James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, Daniel Roos

How the Beatles Changed the World, Martin W. Sandler

The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, Marc Levinson

Seeds of Change: Five Plants That Transformed Mankind, Henry Hobhouse

Salt: A World History, Mark Kurlansky

How Algorithms Changed the World (recently sighted, though editions disagree on when the change actually occurred)

Announced. Blurbs welcome.

No publication date.

The subject varies. The promise does not.

Unlike “The Last—”, which positions the reader as a witness to disappearance, “How X Changed the World” casts the reader as a retrospective student of inevitability. The change has already occurred. The world has already been altered. You are here to be briefed, not consulted.

Taken together, these two title forms appear to divide modern time neatly in half.

On one side, loss framed as destiny.

On the other, transformation framed as fait accompli.

In both cases, agency quietly recedes. Nothing ended because of us. Nothing changed because we chose it. Things simply happened—finally, decisively, and elsewhere.

This pairing may be more than a publishing convenience. It may be a linguistic coping mechanism. When history feels too large to steer, we repackage it either as something already gone or something already settled. We mourn or we marvel, but we rarely intervene.

Which returns us to a standing suspicion of the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists: language itself may be the most active archaeological site we possess, and we are walking across it every day without noticing the dig beneath our feet.

Words accrete meaning the way soil accretes layers. Titles fossilize moods. Phrases recur not because authors conspire, but because a culture quietly agrees on what feels plausible to say. When “The Last” becomes a default opening move, it may reveal less about endings than about how we have learned to experience time—always arriving just in time to observe what we believe has already slipped past us. When “How X Changed the World” proliferates, it suggests a parallel instinct: to explain transformation only after it has become irreversible.

A title is a small thing. But small things—cod, paper, potatoes, algorithms—are precisely what these books insist upon. Perhaps because small things changing the world feels safer than admitting that we did, collectively, and without a clear plan.

It would be worth someone’s while to conduct a longitudinal study of book titles over the past half-century, not for their plots, but for their tonal assumptions. We would volunteer to do this ourselves, but such a task would require patience, suspicion, and a willingness to read backward.

Perhaps it is time to bring our Backward Scholar out of retirement.

—Paige Turner

Sub-Sub-Librarian, C-of-C-C Newsletter

More from:

Leave a comment