ART NOT AS REBELLION, BUT AS EVIDENCE

— An exposition by Phyllis Stein, Art Critic-at-Large

Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists

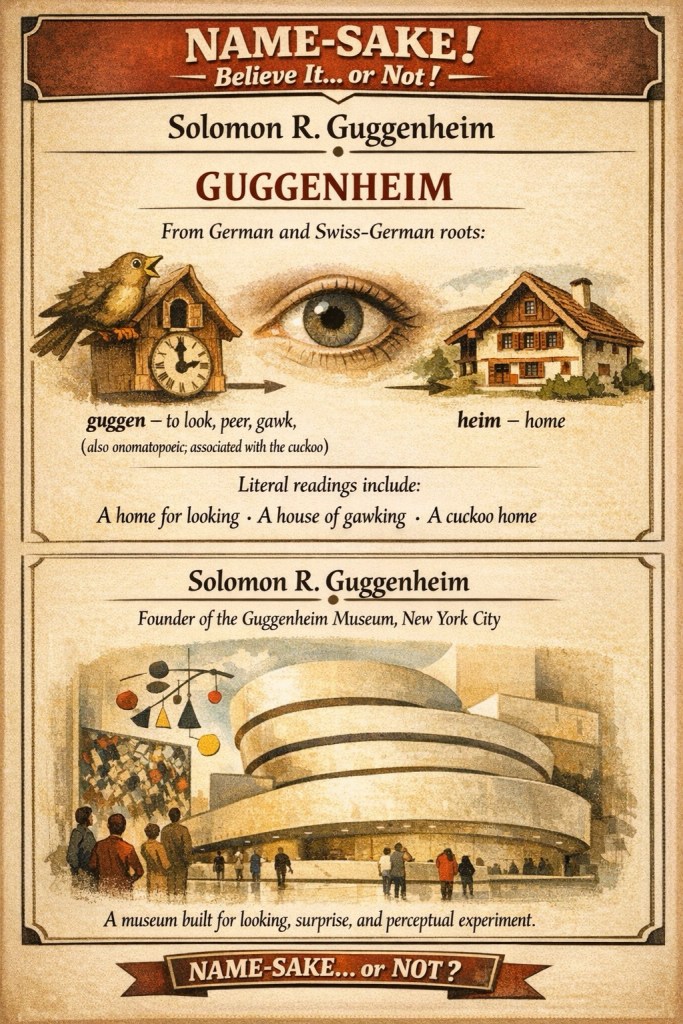

There is a long-standing superstition in art culture that noticing obvious correspondences is a form of bad manners. Yet names, like buildings, often tell you exactly what they are if you are willing to look without embarrassment.

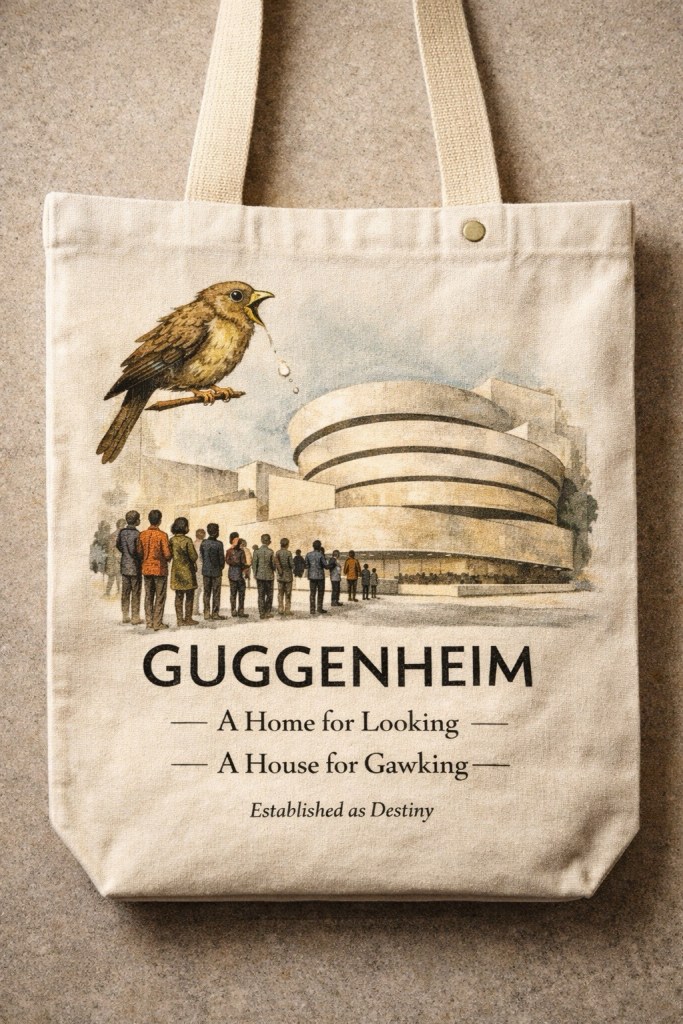

Guggenheim is one such case. A home for looking is precisely what was built—spiraling, insistent, and unapologetic. That some of the looking involves works that unsettle, disorient, or strike the unprepared viewer as slightly cuckoo seems less an accident than a fulfillment.

As for the word Philistine: it is usually deployed as an insult by people who mistake obscurity for refinement. Historically, the Philistines were seafaring migrants from the Aegean world—likely kin, in a broad ancestral sense, to many modern Europeans and Council members, including those who now queue dutifully along Fifth Avenue.

If noticing that a cuckoo home became a cathedral of modern art makes one a Philistine, then perhaps the charge should be reclaimed. After all, someone has to notice what is plainly in front of them, or the whole structure collapses into theory.

Seen this way, the art housed within such a structure should not surprise us. A home for looking is precisely where one would expect to find work that tests the limits of recognition itself. Modern abstraction, often treated as rebellion or provocation, may instead be understood as an honest register of perceptual strain.

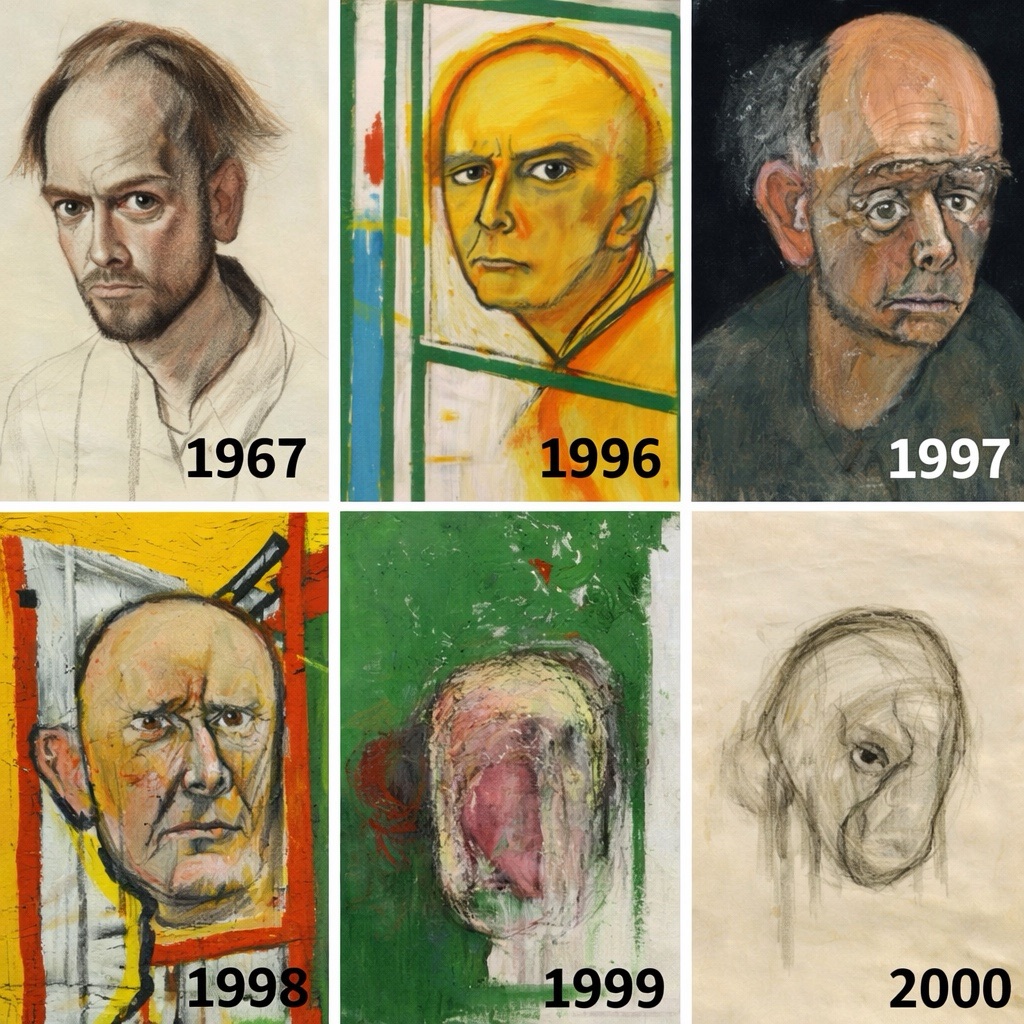

The analogy is easiest to see in the late self-portraits of William Utermohlen, produced as dementia advanced.

Representation did not vanish; it unraveled. Faces flattened, spatial coherence weakened, and yet the act of looking persisted. These paintings are not theoretical exercises. They are documents of vision continuing after certainty has begun to fail.

There is, quietly, a nominative resonance in the name Utermohlen itself. Derived from German elements meaning outer or beyond (uter / äußer) and mill (Mühle), the name suggests a place of turning or grinding at the edge rather than the center. It is difficult not to notice how closely this echoes the arc of Utermohlen’s late work: identity no longer commanded from within, but processed repeatedly at the margins of the self—vision continuing, even as integration weakens

A comparable pattern appears, less clinically but no less tellingly, in the late work of Willem de Kooning, where form yields to gesture and integration gives way to motion. Whether this shift resulted from illness, age, or aesthetic conviction matters less than the resemblance it bears to cognitive thinning: the eye still active, the hand still working, the whole increasingly difficult to hold together— cultural dementia.

When such developments appear repeatedly at the level of individual genius, they invite a broader reading. Certain modern artists function as bellwethers, signaling in advance what later becomes general: a culture still capable of intense looking, yet progressively uncertain of what it is seeing. Abstraction, in this sense, is not cultural vandalism but cultural symptom—vision persisting as coherence weakens.

That a building named Guggenheim—a home for looking, gawking, even the occasional cuckoo surprise—should come to house such work suggests that nominative determinism does not announce itself loudly. It fulfills itself quietly, architecturally, and with remarkable patience.

— Justin Aldmann

Retirement and Senescence Correspondent

Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists

**************

Leave a comment