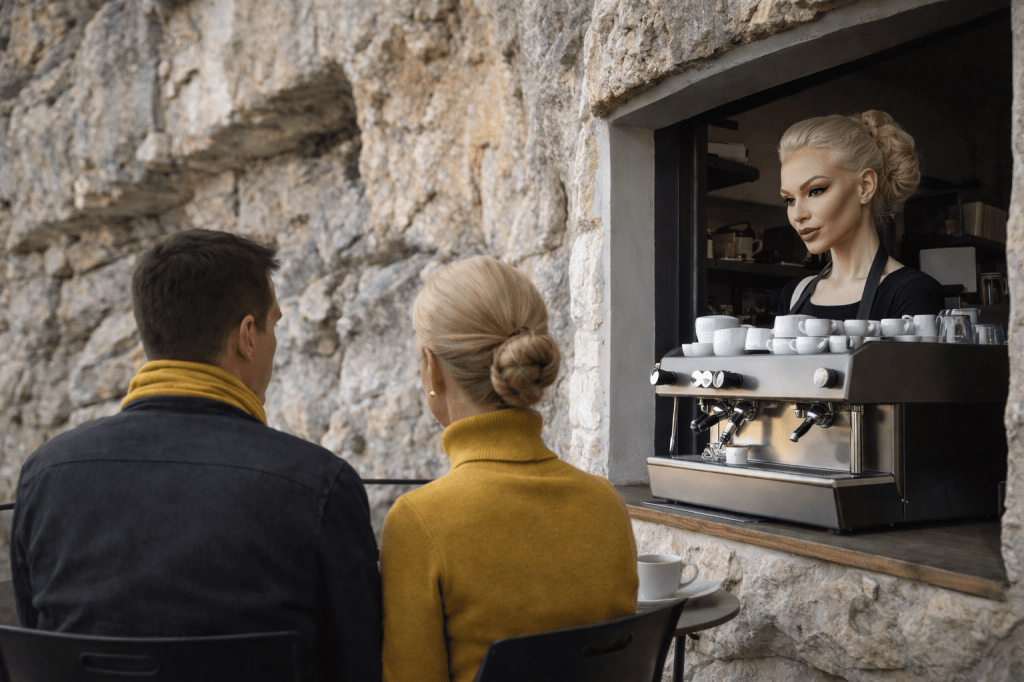

The Outcrop Café had been built where the hill forgot to keep its secrets. Behind the counter, the rock face was exposed in clean vertical bands—layers visible enough that even the espresso machine seemed to hum with geological awareness.

Mrs. Begonia noticed this first, as she usually did. She had a gift for spotting when the background was doing the real work.

John St. Evola followed her gaze, set down his cup, and smiled faintly.

“People assume history is chronological,” he said. “It’s really stratigraphic.”

She didn’t ask him to explain. She never did. She waited.

He gestured toward the lowest visible band of stone.

“Down there,” he said, “before philosophy learned to introduce itself, images didn’t represent things. They were things.”

She nodded. “The Paleolithic layer.”

“Exactly. Those female figures—heavy, exaggerated, unapologetic. Not portraits. Not ideals. Instruments. Fertility compressed into form. No one wondered whether they were accurate. Accuracy hadn’t been invented yet.”

Mrs. Begonia stirred her coffee.

“They didn’t lie,” she said. “They didn’t promise anything.”

“Right,” John replied. “They participated.”

His finger moved upward along the rock face and stopped at a smoother, lighter band.

“Then comes a long stretch where certainty settles in,” he said. “The classical world.”

She glanced at a calm, proportioned Venus reproduction near the counter.

“Essentialism,” she said. “Teleology.”

“Yes,” John replied. “The belief that bodies have intelligible natures and proper ends. Sculpture didn’t invent beauty—it uncovered it. Proportion wasn’t fashion. It was truth made visible.”

The classical-to-human image was inserted by the photographer

She considered this.

“So the female form wasn’t symbolic,” she said. “And it wasn’t questioned.”

“It was destiny,” John said. “The body as something already complete, already knowable.”

Mrs. Begonia smiled faintly.

“The last time anyone believed mirrors could be trusted.”

John’s finger continued upward and paused again, this time at a darker, more vertical band.

“This layer is often missed,” he said. “But it held the cliff together for centuries.”

“The Middle Ages,” she said.

“Yes. And its governing assumption wasn’t ontology or epistemology, but analogical realism.”

She leaned back slightly. “Meaning passes through matter.”

“Exactly,” John said. “Reality is real. Meaning is real. But meaning doesn’t stop at the surface of things. Stone figures of women weren’t ideals or symbols. They were vessels. Signs that participated in something beyond themselves.”

Mrs. Begonia thought of a carved Madonna—elongated, serene, unpossessive— like the barista.

“So the body didn’t have to explain itself,” she said. “It was allowed to point.”

“Precisely,” John replied. “The female form mattered because of what it carried, not what it displayed.”

His finger moved higher, into rougher stone.

“Then the confidence fractures,” he said. “Modernity arrives. Being itself becomes unstable. Sculpture begins to distort—not to deceive, but to investigate.”

Mrs. Begonia studied a nearby image of a modernist reclining figure.

“Distortion,” she said, “but honest distortion.”

“Ontology at work,” John said. “What remains when surface meaning is stripped away? Stone stays stone. The body stays prior. Existence under pressure.”

She took a sip.

“Back when distortion still had the decency to stay on the pedestal.”

John smiled and they proceeded to the topmost layer.

“And now,” he said, “we reach our own.”

She didn’t look only at these sculpted ones this time. She thought of the barista.

“This is where the question changes,” he continued. “Not what is the body, but how do we know what we’re seeing is real at all.”

“Epistemology,” she said.

“Dragged out of philosophy and into daily life by AI,” John replied. “Images without referents. Faces without moments. Photography once reassured us—light touched flesh, the world left evidence. Now images arrive fully formed, owing reality nothing.”

“And sculpture,” she said, “has crossed the boundary.”

“Yes,” John said. “Sculpture becomes flesh. Procedures replace chisels. Implants replace marble. The artwork no longer depicts the body—it revises it.”

Mrs. Begonia leaned back, watching reflections slide across the mirror.

“So we’re not just questioning images,” she said. “We’re questioning bodies.”

“And authenticity,” John added. “What counts as real. What counts as finished.”

She watches the seated women —faces smooth, symmetrical, slightly… elsewhere.

“Have you noticed,” she said, “that no one is trying to look classical anymore?”

John raised an eyebrow.

“They’re not aiming for ancestry,” she continued. “They’re aiming for arrival. Somewhere new.”

“The alien aesthetic,” John said.

“And it’s intentional,” she replied. “Not botched. Not accidental. People are choosing to look like they came from another planet.”

John considered this.

“Every age sculpts the form it believes is coming next.”

Mrs. Begonia smiled.

“Concept art,” she said.

“For the self,” he replied.

They sat quietly for a moment. Somewhere, someone posed for a photograph that might or might not have needed to be taken.

“So ontology isn’t over,” she said at last.

“No,” John replied. “It’s still holding up the building.”

Mrs. Begonia glanced once more at the mirror.

“Epistemology just runs the renovation.”

“And installs better lighting,” John said.

“And charges admission,” she added.

They finished their coffee. The rock face remained exposed. And somewhere between stone, image, and flesh, the present layer continued to settle—still warm, still uncertain, quietly redesigning itself for a future no one is entirely sure is real.

***

Leave a comment