—A working note from the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists

—By Way of a Street Corner Wail, a Soapbox, and the Useful Blubber of Meaning

—by John St. Evola

John did not call a meeting.

There was no hall, no banner, no sign-up sheet. It was a damp, drizzly November of the soul. John stood instead on a godforsaken corner in the Pennsylvania Wilds, in a town that had once been on the way to somewhere and now mostly existed as proof that routes can forget themselves. The county had only two traffic lights, and one of them no longer worked. The intersection remained orderly anyway. Drivers slowed. They nodded. They waved one another through. It worked because the people there had inherited a sense of how order is maintained when no one is watching and no machine is instructing them.

He had brought what looked like a small wooden soapbox—scarred, practical, untheatrical. In fact, it was an old shipping crate that had once held dynamite. This part of the county used to manufacture TNT, enough of it cut Panama Canal and rearranged continents.

(Editor’s aside: this is not a metaphor invented for effect. Explosives were manufactured here, and crates like this one still can be found locally.)

What made the scene quietly absurd was not the box but the wire: a microphone clipped to the edge, a phone balanced carefully on top. John, standing on a container built for explosive force, alone on a near-empty street, podcasting to the world.

A global address delivered locally. Bandwidth in a place with barely any pedestrians and an unreliable cell signal to match.

A few Council members lingered at a distance, recognizable mostly by posture. A passerby slowed. Another decided not to cross the street just yet. John was not performing. He was accounting. Explanation, when done without haste, still gathers weight.

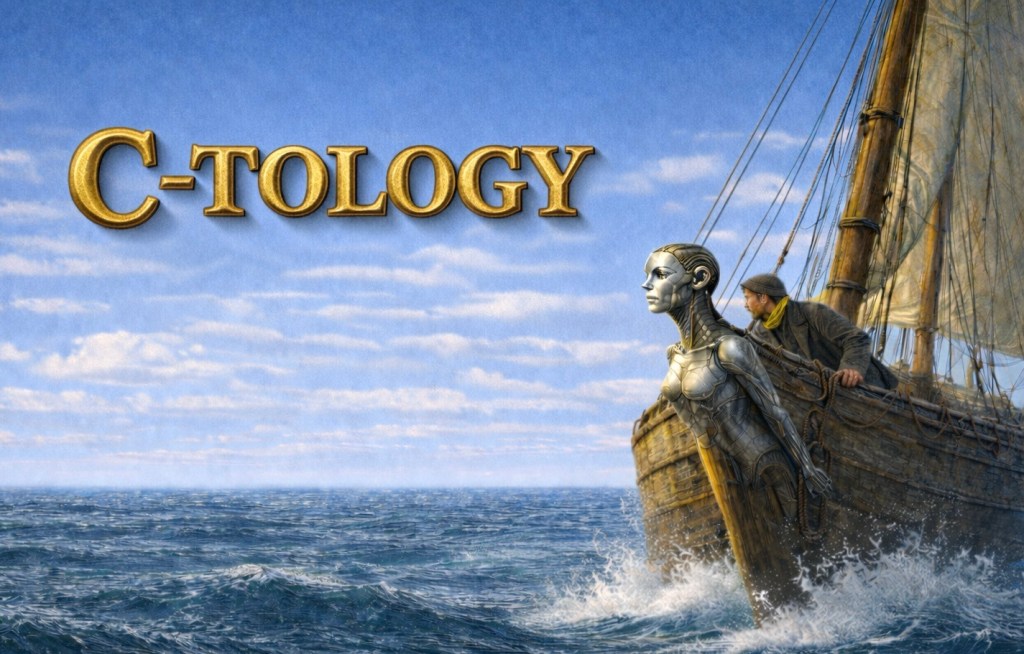

“This,” he said, gesturing not outward but downward—to the box, the pavement, the accumulated residue of things that endure—“is an introduction to something we’re calling C-tology.”

He let the word sit.

“C-tology is how we explain what the Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists is actually doing here. Not as a mission statement, and not as persuasion. We didn’t set out to do this. At some point we noticed it was already happening, and something clicked. C-tology is simply a way of describing the materials we found ourselves surrounded by, and why we decided they were worth conserving.”

He adjusted the microphone, not for volume but for patience.

“It isn’t theology. It isn’t ideology. Think of it instead as classification. Inventory. A method for approaching something very large without pretending it can be summarized cleanly.”

He did not name the creature. He spoke instead of what keeps such things afloat.

“Some of what we do looks excessive from the outside,” John continued. “A surplus of language. Old references. Jokes that carry more weight than they immediately spend. Call it Council blubber, if you like. Blubber isn’t decoration. It’s insulation. It remembers heat. It keeps bodies buoyant in cold water.”

A logging truck passed too loudly. The podcast did not flinch.

“C-tology is where we explain what the Council is doing without turning it into a slogan. Not because explanation is avoided, but because explanation survives best when it is handled rather than declared. Straight lines trigger defenses. Side approaches allow contact. You don’t begin with the whole. You begin with what can be handled.”

He paused, then went on.

“There’s a story people tell about a country rock album from the late sixties—Sweetheart of the Rodeo by The Byrds. The album arrived wearing quotation marks it didn’t ask for. Rock audiences assumed it was ironic—hippies cosplaying country, faith delivered with a smirk. Yet the record wasn’t conceived as parody. The band approached the material straight. The irony came later, supplied by listeners who needed a buffer.”

Lake Louise: the Council’s Ultima Thule—the Banff of the mind, the place we always meant to go.

He looked down the empty street, then back to the device carrying his voice far beyond it.

“That distinction matters. Because irony, in late modern life, is often not the intent—it’s the delivery system. It’s the packaging we apply to meaning so we can get it past our own resistance.”

He continued, now settled into the rhythm of the thing.

“Listen to ‘The Christian Life’ and tell me you don’t hear raised eyebrows. In 1968, it sounded like mockery.

And yet history played a counter-melody. McGuinn and Hillman would later become Christians. The form did not require sincerity in advance. It worked by residence.”

Here John slowed, as if the street itself were listening.

“Irony that carries nothing evaporates quickly. But irony that carries a form—a melody, a ritual, a grammar older than the joke—can complete the delivery even if the sender disavows the contents. The joke opens the door. The form walks in. The joke leaves. The furniture remains.”

“This is the pattern the Council pays attention to.”

The microphone held.

“Late modernity thought irony was a solvent. It turns out to be a courier. A sealed envelope. Meaning arrives intact even if everyone pretends it’s only visiting.”

He shifted his weight on the crate, once stenciled for TriNitroToluene.

“The Council operates between jest and earnest not because it can’t decide, but because that band is where transmission still happens. Too earnest, and nothing gets through. Too jokey, and nothing stays. Satire and parody, like trinitrotoluene (TNT), can be volatile—stable in transit, unpredictable if mishandled, and dangerous to those who treat them casually. Handled carefully, irony slips past the immune system of the age and smuggles continuity under the cover of play

(With a touch of Walter Mitty. Closely supervised.)

He allowed himself the smallest smile.

“The funny part is this: I’m standing on a near-abandoned street corner, speaking to almost no one in front of me—and, by way of a phone and a wire, to more people than I can see. The scene looks ironic. The content is not.”

He tapped the edge of the box once, lightly.

“C-tology exists to explain the Council this way—by specimens, by field notes, by useful excess. Not to announce the whole, but to keep the body warm long enough for understanding to arrive.”

Then, without ceremony, he stayed with the first example—Sweetheart of the Rodeo—using it to show how something played at arm’s length can quietly become a place one lives.

Somewhere between jest and inheritance, the signal kept traveling.

Leave a comment