—We are only passing through, like that’s all we have to do?!

The morning was clear and already warm on the rock face, the kind of day when sound carries and small movements matter. A group of children was partway up the cliff, moving slowly, helping one another find footing, their attention fixed on hands, ledges, and balance rather than on being observed.

C-tology is the Council’s way of naming errors before they harden into wisdom. Not mistakes of fact, but mistakes of orientation—the kinds that sound calm, reasonable, even virtuous, and are therefore the hardest to correct. The Council-of-Concerned-Conservationists has long held that ideas must be tested where they carry weight, not where they can float.

Some lessons survive a desk. Others require gravity.

It was agreed afterward that the lesson could not have taken place anywhere else.

That was when John St. Evola told them to stop for a moment and open the palm of their hand.

“Look at it,” he said. “Really look.”

Now realize that you have been alive for a very long time. The living essence of what you are has been passed down through countless births. After aeons it is still alive and has potential to keep going on. It is ever new in each newborn generation even though each iteration will eventually age and perish.

He let them close their hands again.

Now forget that Buddhist-inspired b.s. philosophy that you might pick up along the way—the one that tells you none of this really matters because it passes. This is not a dig against someone’s religion. It is an opinion about a decadent interpretation, one only fit for a dying race, just as it was when it first surfaced in the East. It flatters exhaustion. It turns withdrawal into insight. It teaches people to confuse impermanence with permission.

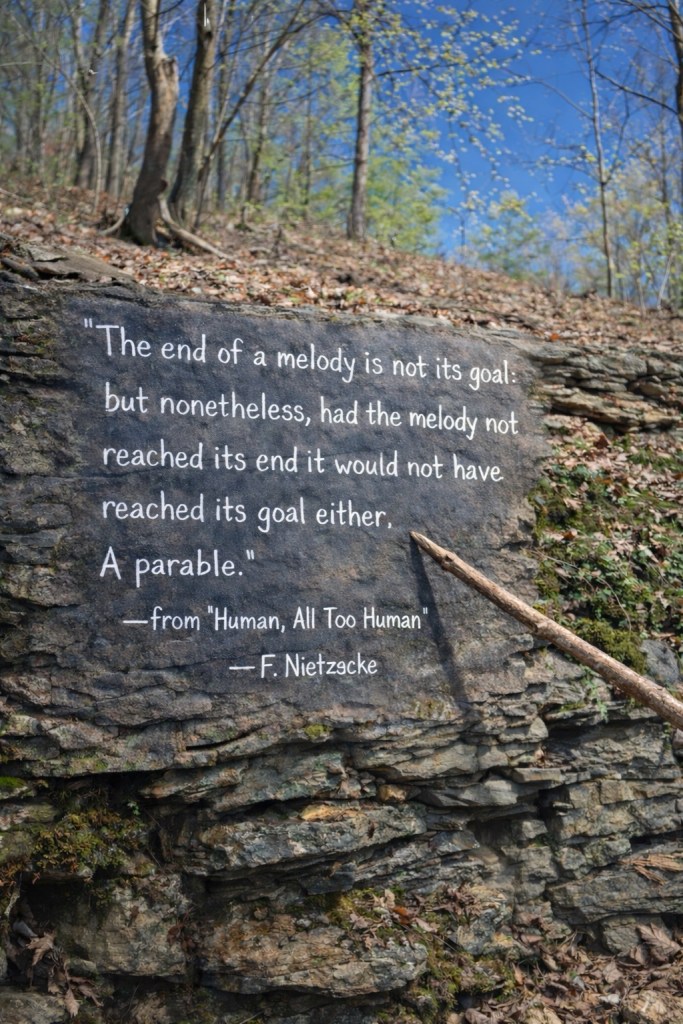

On the way up and behind him, chalk markings were already worked into the rock face itself. No one questioned when they had been written. White dust clung to the stone as if the cliff had always been in the habit of explaining itself.

He did not read the words aloud. He let the kids read them themselves if they could, tracing the lines with their eyes while balancing their weight.

Then he said, “That doesn’t mean what people think it means. The end of something is not the same as its failure. A song doesn’t stop because it failed. It stops because that’s where the song goes. Ending is part of the shape. Without it, there is no meaning at all.”

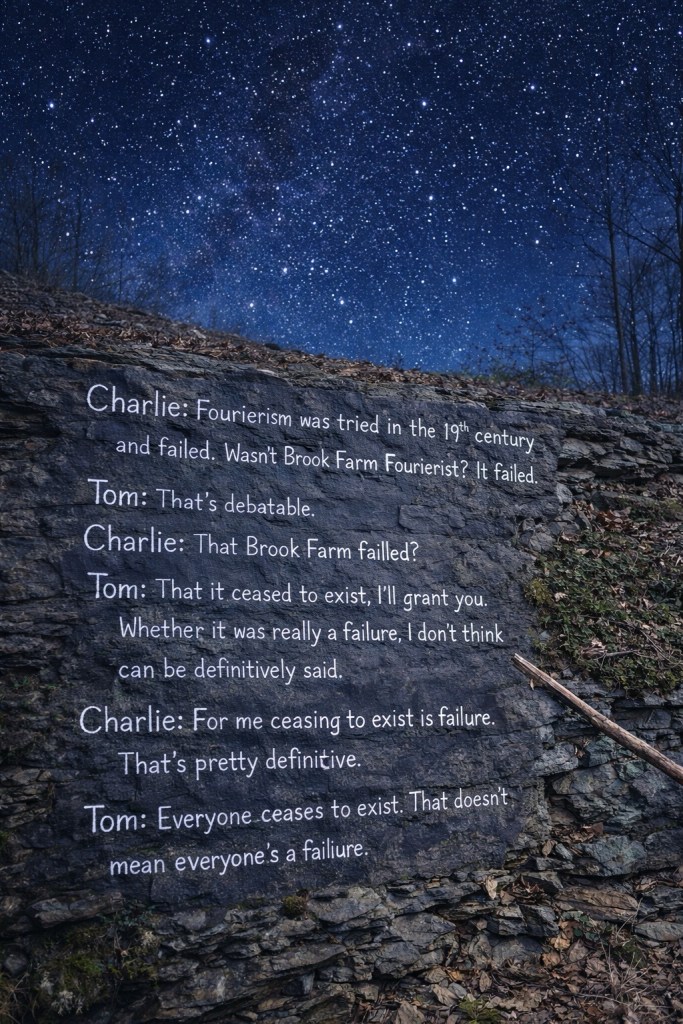

Further along the cliff face, another stone bore more writing, laid out slower this time, in more lines than before, the chalk caught in the seams as though the words had migrated there on their own

He lifted the stick and held it there, indicating the line without touching the stone.

“If ceasing to exist were failure,” he said, “then everyone who ever lived would be a failure. Nothing that ends could be said to have mattered. That’s obviously false, and yet people believe it every day without noticing.”

Below him, one of the children lost footing for a second. Another reached down immediately and steadied them. John watched this without comment.

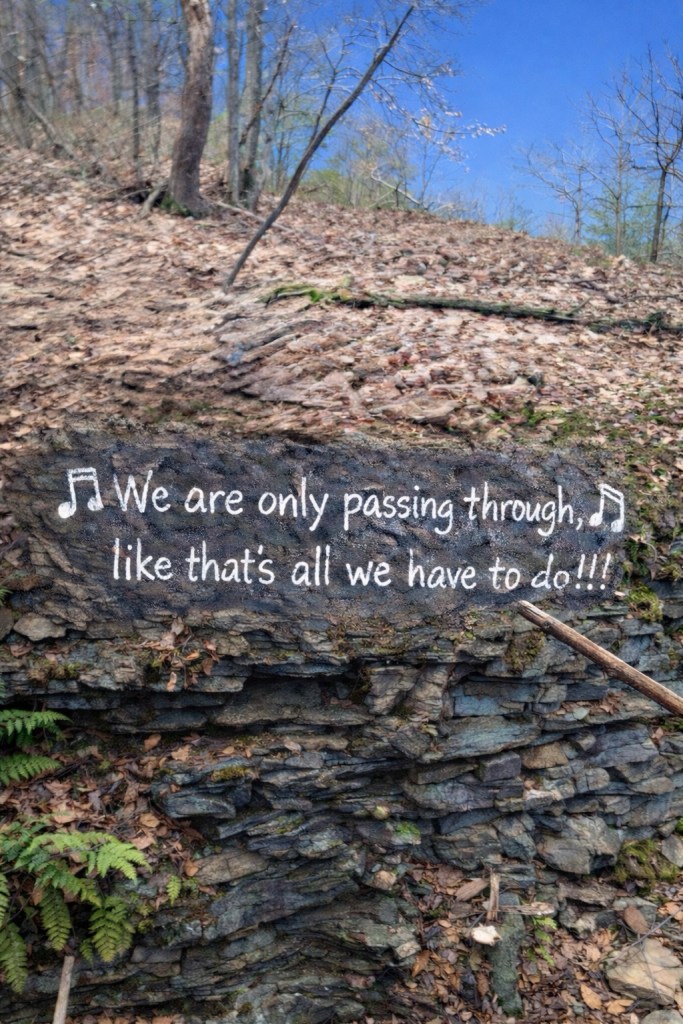

When they reached the next level at the top of the cliff, the stone flattened out briefly, forming a narrow ledge. On the rock face there—chalked directly onto the stone as if someone had paused mid-climb and written it without ceremony—were a few lines of lyrics, scrawled unevenly and already dusted by wind.

“As the lyrics state,” he continued, turning back to the phrase already written on the stone, “We are only passing through. But the operative phrase is the one everyone skips.”

He tapped the underline.

“Like it’s all we have to do?”

He shook his head, not angrily, just once.

“Passing through is not the work. Passing through is the condition under which the work must be done. You don’t climb because the cliff is permanent. You climb because you won’t be here long.”

He looked again at their hands—chalked now, scraped, gripping stone that would not remember them.

“Now get busy,” he said.

Then, after a pause, softer, almost as an aside: “But first, take a few minutes to listen to this song done properly.”

“This is so obvious. I don’t know why I have to even remind you and keep repeating it.”

He stepped aside. The writing remained. The kids moved on—some understanding, the rest still oblivious.

“So we’re not just passing through?”

“We are. You just still have to do stuff.”

“I’m hungry.”

They laughed and moved on.

**************

More SONIC CONNECTIONS: HERE

Leave a comment