—Average was never about equal sharing—only proportional loss.

From a past feature in the COUNCIL-OF-CONCERNED-CONSERVATIONIST Newsletter that appeared on a random and infrequent schedule, devoted to those nagging, unresolved questions—the ones that refuse to stay put. Possibilities. Alternative answers. The loose threads polite arguments prefer to trim away.

In yet another review of a book review, we turn to The End Of Average, which argues—convincingly—that the exception is not an error around the rule, but the rule itself. Systems built around “the average person,” it turns out, are aiming at someone who does not exist.

And yet—

What explains the fact that I have such a hard time finding work pants in my size?

Is it because I am so perfectly average that my size flies off the shelves before I arrive? Or because manufacturers, guided by abstract demand curves and tidy charts, simply make fewer pairs in that range? Or is it that the demand is statistically “low,” even if the number of actual people is not?

There was a time when I had a field day in military surplus stores, particularly with Dutch army wool pants. Most of them fit me well enough, even leaving room for thermals. This was not because the Dutch had secretly designed their military around my proportions. Quite the opposite. The Dutch are among the tallest populations in Europe, which meant that planners, working from statistical distributions rather than bodies, compensated by producing large numbers of mid-range sizes—hedging toward an average that, in practice, fit fewer Dutchmen than expected

My own build simply fell into that statistical slack. My ancestors, it seems, found no evolutionary advantage in adding an extra four inches of biological mass between ankle and shin. When you think about it, that narrow segment is almost the entire difference between a short person and a tall one.

So why were there so many surplus pairs in sizes that few Dutchmen themselves could wear?

Did ideological rigidity play a role in procurement? Did planners overestimate recruitment from South Moluccan units or Dutch female auxiliaries? Or was it simply a statistical artifact—planning by averages, producing abundance where reality required variation?

Who knows. But wool pants, incidentally, are excellent when sitting on the ground in the woods. They insulate well. They resist moisture. Reality has a way of rewarding accidents.

This is the quiet point of the book.

The average pilot, as the U.S. Air Force eventually discovered, did not exist. Cockpits designed for the “average” fit no one well. They were shooting at a target that wasn’t there. How could they hit it?

Statistics do lie—not maliciously, but structurally. They describe populations, not persons. They are tools mistaken for truths.

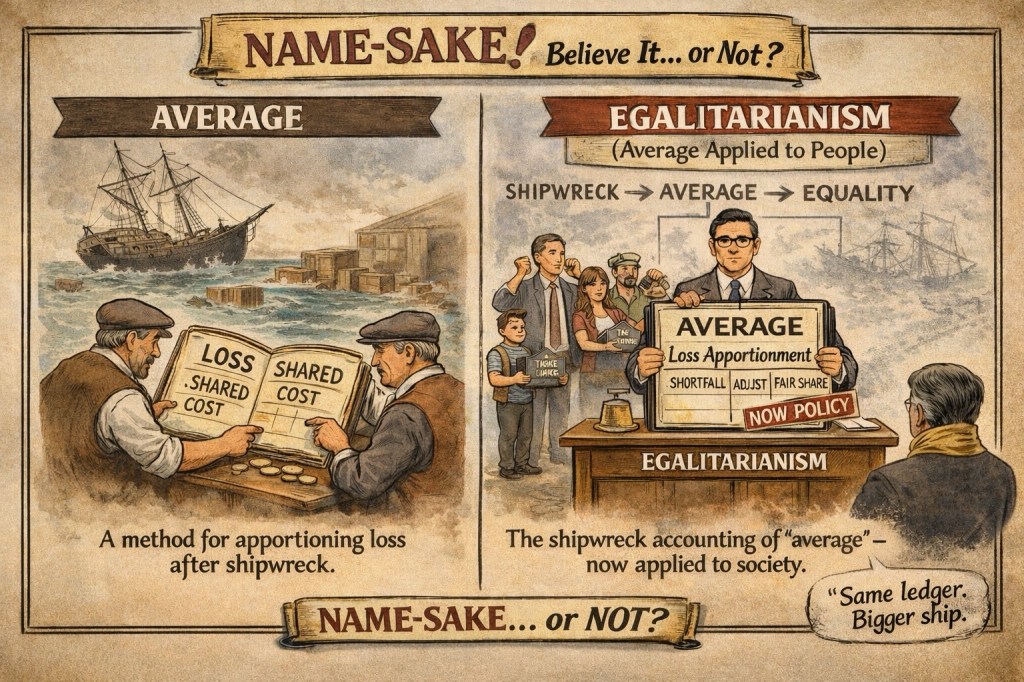

There is a revealing parallel here with the modern worship of equality, not as a moral impulse, but as an idealized condition—a thing to be realized, enforced, and measured.

Like the average, equality works poorly when treated as an abstraction rather than a judgment. In economics, it fails almost immediately. We do not all contribute equally. We do not exert equal effort, possess equal abilities, or bear equal responsibility. Every large-scale attempt to enforce equality as a final state has collapsed under its own contradictions.

And yet.

Within the family, something like equality has worked since time immemorial.

Parents labor and provide wildly out of proportion to what their children contribute—or even deserve. The youngest, weakest, and least productive receive the most care. This is not experienced as injustice. It is recognized instantly as love, duty, and sanity. Not equality as sameness, but fairness shaped by relationship, need, and context.

There it is again. That “and yet.”

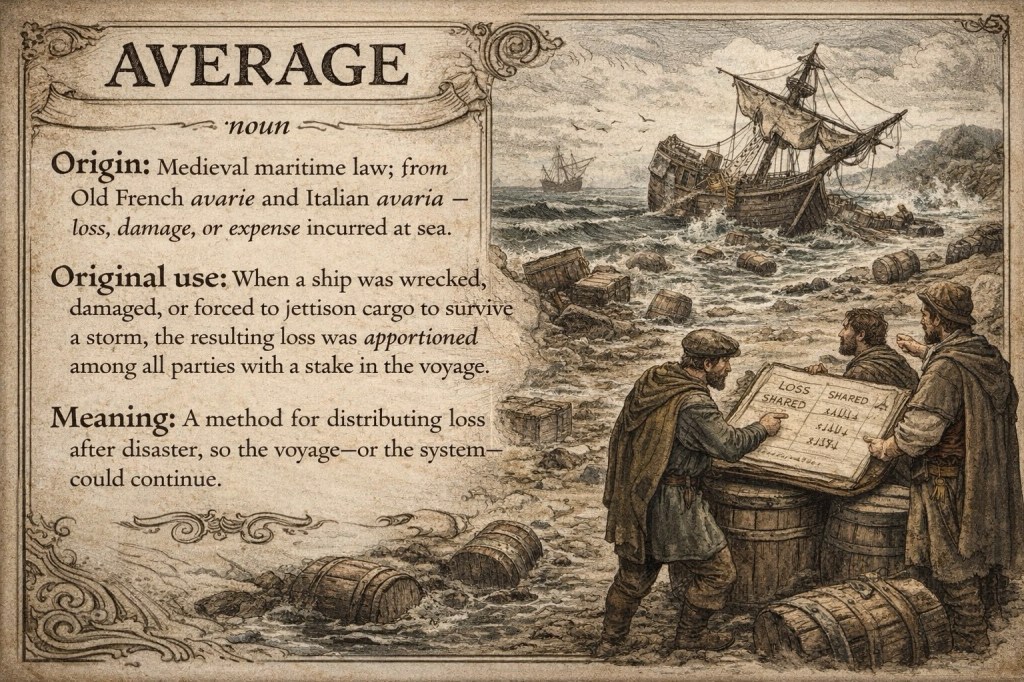

Finally, it is worth noting what the word average originally meant. It had nothing to do with describing people at all. Its origins lie in maritime law, in the aftermath of disaster:

“Originally denoting a charge or customs duty payable by the owner of goods to be shipped, the term later denoted the financial liability from goods lost or damaged at sea, and specifically the equitable apportionment of this between the owners of the vessel and the cargo (late 16th century); this gave rise to the general sense of the equalizing out of gains and losses by calculating the mean (mid 18th century).”

In other words, average was about dividing losses after a shipwreck.

—Strongly favored by the large language model

Perhaps that should give us pause.

The modern fixation on averages and enforced equality may be less a vision of human flourishing than an accounting method applied too late, too broadly, and to the wrong domain—an attempt to apportion meaning, worth, and responsibility after abstractions have already run aground.

And yet, in wool pants that fit by accident, in families that give unequally and endure, and in systems that work only when they abandon their ideals long enough to meet reality, something stubbornly human persists.

Leave a comment