Detritus: Mal’Poetica

—The poetry and lyric column of the C-of-C-C Newsletter

It might be a pleasant, delirious, horrific, calming, hubristic, or profound thought that we can be aware that we are the universe becoming aware of itself. Or it may simply be one of those explanations that arrives perfectly fitted to its moment—explaining everything, excusing much, and asking very little in return.

History suggests that ideas often trade reputations over time: today’s ridiculous notions become tomorrow’s infrastructure, while today’s obvious truths quietly fade into décor. With that in mind, we approach the latest “obvious” answer to the meaning-of-life question with curiosity, affection, and a raised eyebrow.

A recent article circulating in the alt-spiritual ecosystem proposes what it calls a “ridiculously obvious” answer to the meaning-of-life question: that to live, to experience, to be—in all its confusion, pleasure, tedium, and contradiction—is itself the point. No hidden code. No final exam. No cosmic résumé.

It’s an appealing thought. Perhaps too appealing. How do we know that by embracing such an explanation we have not simply been seduced by the prevailing language of the moment? “Hey, it’s all part of the whole, man,” has historically been a sentence capable of both enlightenment and a fair amount of bad behavior.

With this in mind, we enlisted our renegade poet Black Cloud to revise a classic song by Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen from the psychedelic age — to put the thump to this conundrum and bang out a few bars on the piano to boot, in an attempt to put it all in perspective.

—Jánosh Alovatski

(Jánosh is our correspondent covering religion and alt-spirituality, who suspects this “ridiculously obvious” explanation may also have his own thoughts lassoed into it. He still has some time left to figure it all out for us — or at least die trying — so we will be patient.)

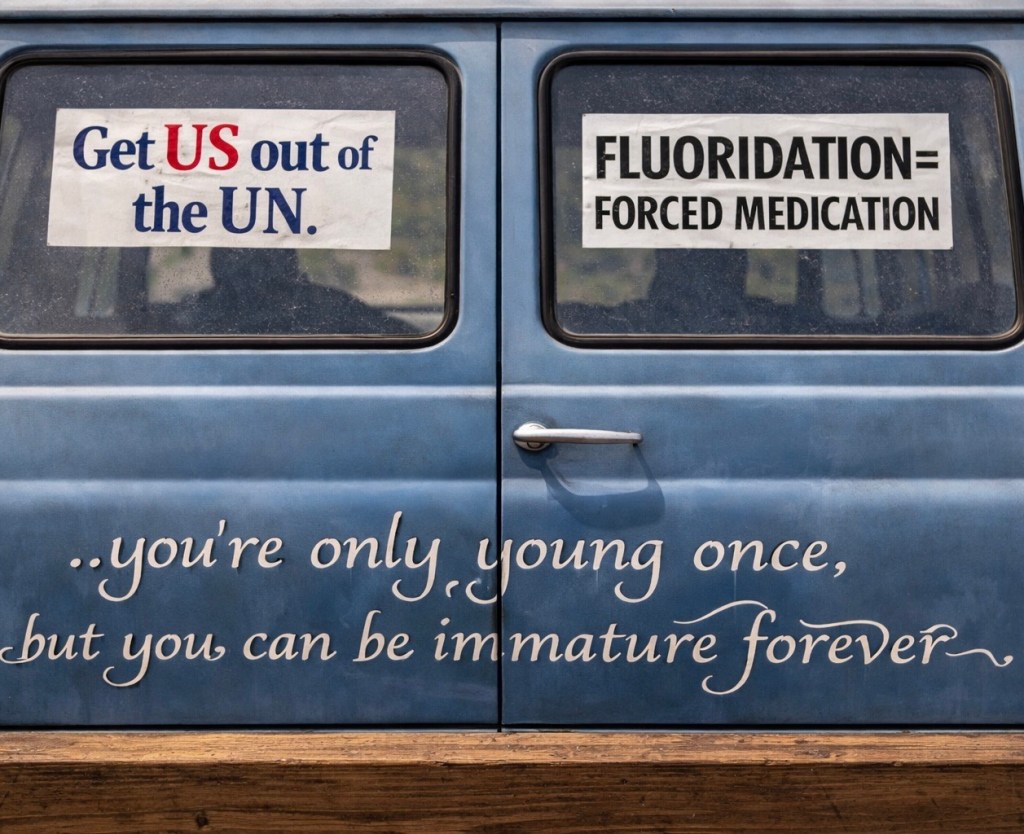

Jánosh related how, in the early seventies, he passed through Ozona, Texas. He and a long-haired hippie friend walked into the local Ford dealership looking for a replacement universal joint for the van that had broken down. The parts counter man, wearing a six-gallon hat, gave them a look that could kill and a replacement universal.

After noticing a full rack of John Birch Society literature in the waiting room of the service department, Jánosh felt the strange urge to tell the Texan, “I’m with you, man,” but knew instinctively that he would neither be understood nor believed.

—The Editors

LOST IN THE ZEITGEIST AGAIN

AND LOST IN OZONA TEXAS, BROKE DOWN IN THE VAN AGAIN

🎶I told ya a million times how I love you.

But honey your old shriveled universal part was just too broke in

So I’ll just relax here,

—half full of being.

Head in the zeitgeist again.

Here we go now—

I’m lost in Ozona again.

I’m lost in the zeitgeist again.

One shot of time, one trip of being

And I’m lost in the zeitgeist again

Now the neon lights are shinin’ bright downtown.

There’s a thousand swingin’ thoughts won’t let me win.

I tucked the kids in bed, heh!, at eight o’clock and then—

I’m gonna head for the zeitgeist again.

Just watch me—

I’m lost in Ozona again.

I’m lost in the zeitgeist again.

One shot of time, one trip to being

And I’m lost in the zeitgeist again

—Commander Cody / Black Cloud

Editors’ Note:

(Filed Late, With the Benefit of Dust and Distance)

It should be noted—though it was not fully legible at the time—that the author was already familiar with John Birch Society literature as a teenager and did not encounter it in Ozona as an anthropological curiosity. What struck him then was not the content itself, but its placement: sitting openly in a service bay and at the curb, integrated into the everyday maintenance of American life — assumed rather than argued.

What has shifted with time is not the author’s awareness of that worldview, but the historical context surrounding it. Many of the Birch Society’s warnings — once dismissed as overheated or paranoid — now read as a form of poetic prophecy: an early, blunt attempt to describe structural power operating beyond electoral visibility. They lacked the later vocabulary of “deep state,” but not the intuition that permanence, administration, and continuity often outlast ideology.

What the Birch Society frequently misjudged were tone, proportion, and sometimes target. What it grasped, with uncomfortable prescience, was that modern power would present itself not as tyranny, but as normalcy — procedural, managerial, and difficult to point at without sounding unhinged.

Reopened as policy debate.

History has a habit of laundering yesterday’s excesses into today’s accepted frameworks. In that sense, the Birch Society may be understood not as correct in the letter, but disturbingly accurate in the rhyme.

This situates the movement.

And it reminds us that ideas, like people, are often truest where they are least articulate.

—The Editors

Jánosh still loves the song. It stayed, like the West Texas wind and past Zeitgeists embedded in his lungs.

Leave a comment