—On Noticing What Holds—

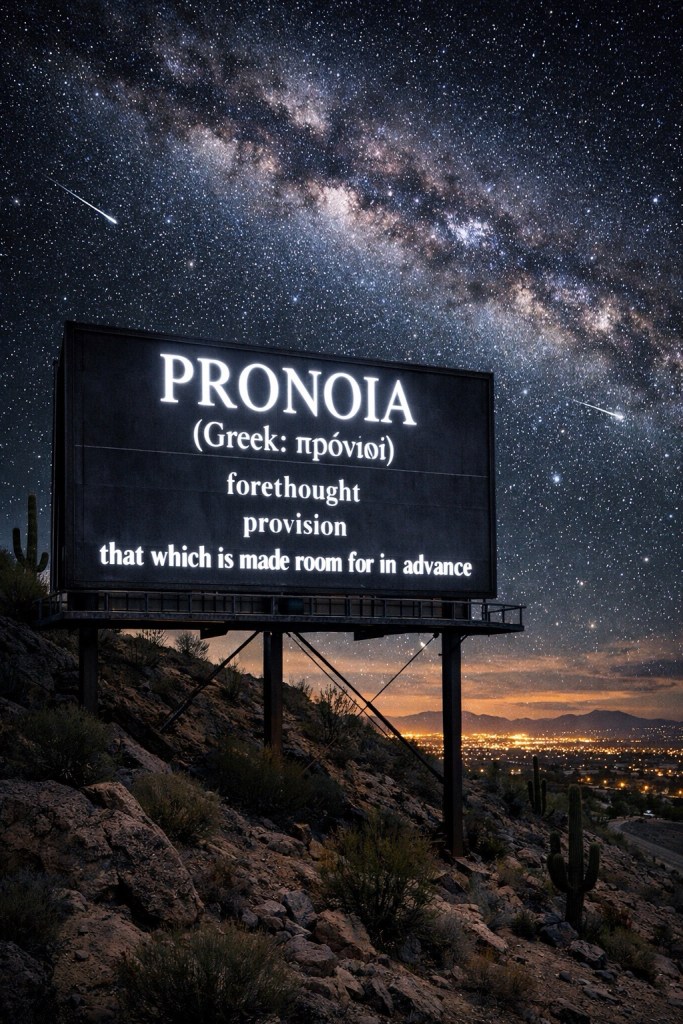

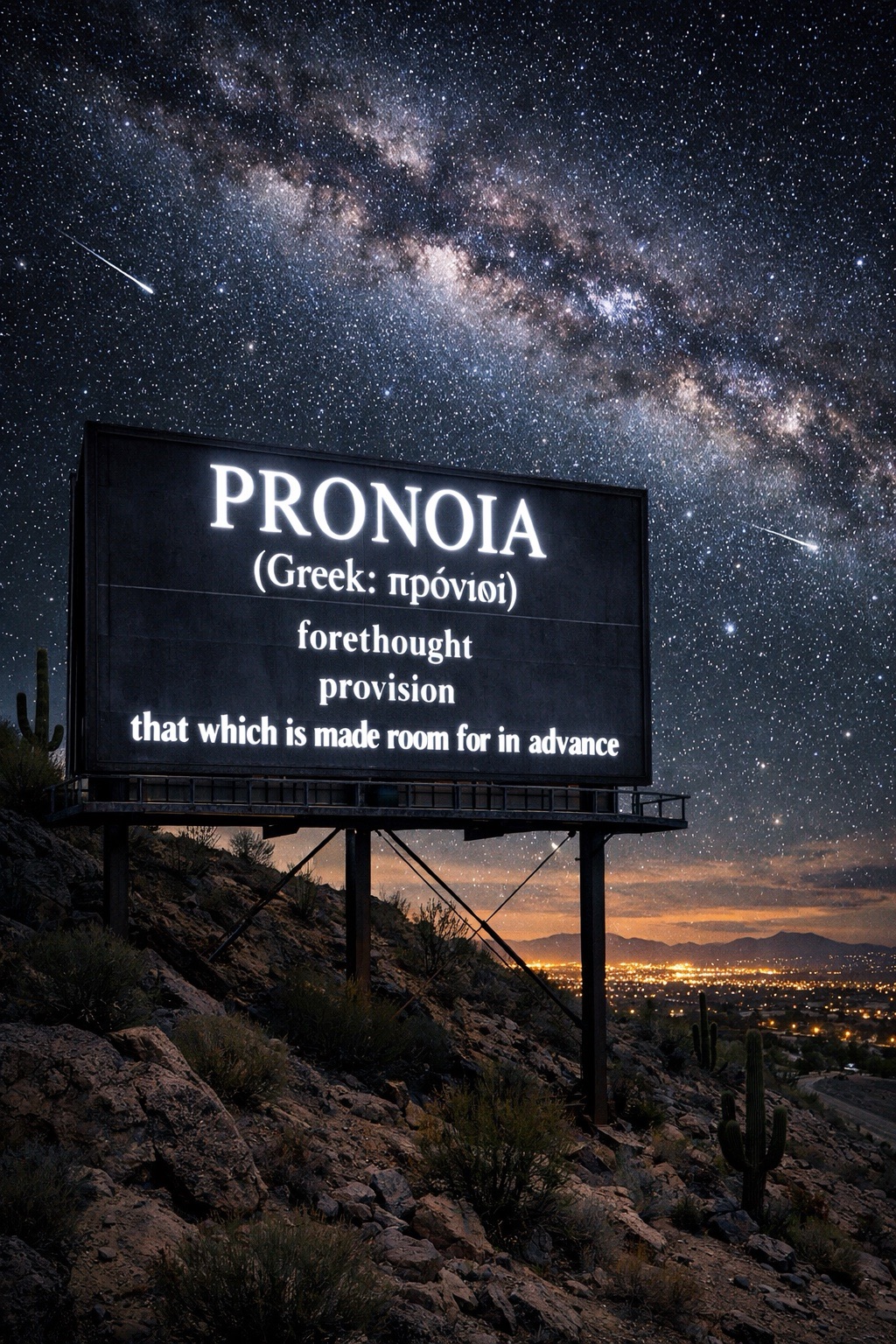

I recently learned the word pronoia, which I’m told is the opposite of paranoia—the belief that events are secretly arranged for one’s benefit rather than one’s harm. The claim alone made me suspicious. Words that present themselves as symmetrical corrections usually turn out to be marketing terms or spiritual solvents. Still, the idea lodged itself where ideas lodge when they’re not asking permission.

Everywhere a sign

Blockin’ out the scenery

Breakin’ my mind

Do this, don’t do that

Can’t you read the sign?🎶

—Five Man Electrical Band

Not long after, while rising in the morning and making the bed—an activity whose purpose is mostly ceremonial, a daily effort to talk myself out of the small despair left behind by mundane dreams—I noticed a cluster of words arriving uninvited: plenum, pleroma, plenty. That hour has always been a threshold for me; dreams and daylight overlap there, and the waking world often seems more vivid and interesting than whatever I’ve just left behind. The words didn’t feel poetic. They felt technical, as though I’d misplaced a manual years ago and was now remembering its table of contents. A plenum, after all, is not a metaphor. It is a space designed to hold pressure so that pressure can be distributed without catastrophe. When it works, you don’t notice it.

It was only afterward—still in that unsettled interval between waking and intention—that I noticed something else. Two tea towels hung side by side on the bunk bed rail. One I had bought years ago at Olympic National Park, honoring the original Mount Olympus. The other I had purchased in Iceland, printed with scenes from Gylfaginning, the Norse account of a cosmos that knows it will not hold. I hadn’t placed them there for any symbolic reason. They were hung simply to cover stored items on the unused top bunk, chosen because I liked the scenes and they were the right size. Only later did it occur to me that they sat adjacent: Greek permanence beside Norse contingency, installed without intention, noticed without hurry. I took this in without interpretation. It seemed enough to recognize that meaning, when it arrives, often does so after the fact, attaching itself to what was done for other reasons.

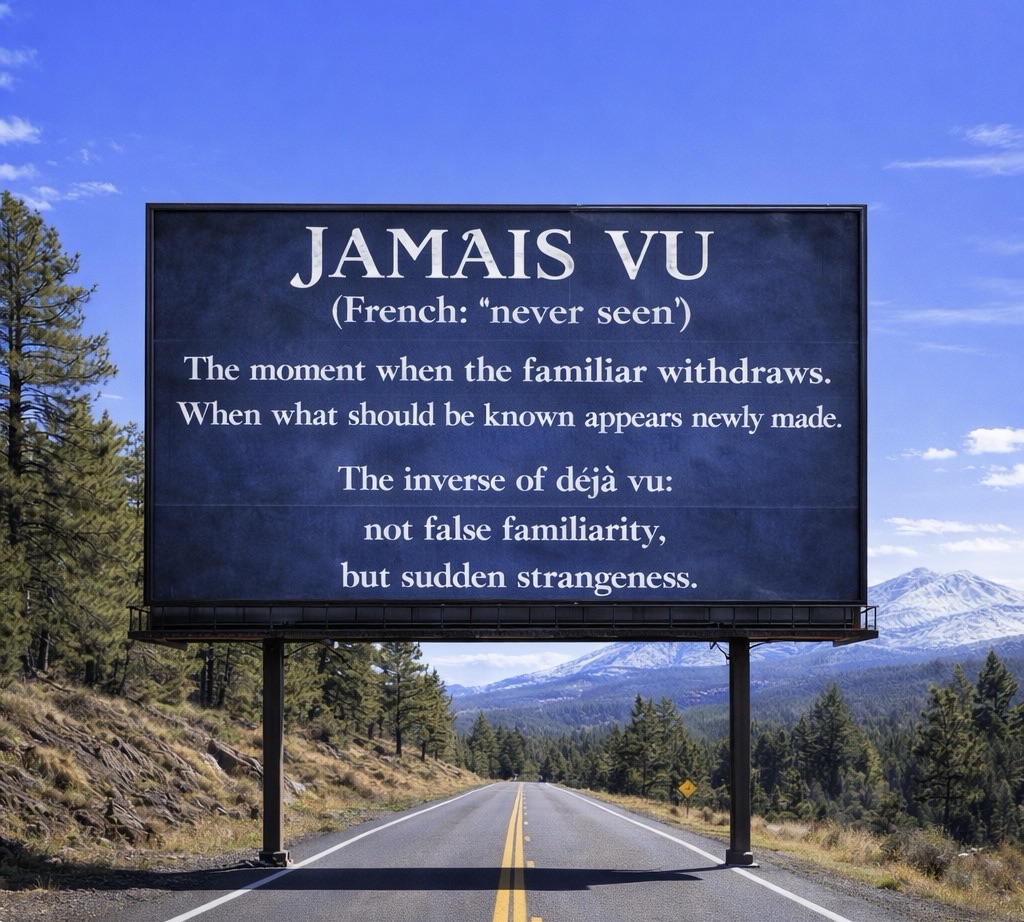

Only later did I learn there was a word for this kind of delayed recognition—the opposite of déjà vu. Jamais vu names the moment when something entirely familiar suddenly appears strange, not because it has changed, but because the habit of overlooking it briefly fails. It isn’t confusion or novelty. It’s familiarity seen clearly, without the anesthetic of repetition. In that sense, it felt like the perceptual cousin of pronoia: not the belief that things are arranged for us, but the quiet realization that we’ve been standing inside arrangements we hadn’t quite noticed.

At some point, a memory surfaced. Years ago, driving at night through a desert city, I was struck by the fact that nothing was going wrong. Traffic lights changed color. Drivers obeyed them. Thousands of strangers piloted heavy machines at speed without swerving into one another. Disorder was possible everywhere, yet coordination was the dominant condition. I remember thinking at the time that this was more remarkable than any breakdown—and also more easily ignored.

Later, the memory sharpened. I remembered standing on South Mountain at night, looking out over Phoenix as it spread across the desert—a disciplined grid of lights, every intersection illuminated, traffic moving as if by mutual agreement. Cutting through it was a diagonal road, older than the grid, following terrain rather than plan. The city hadn’t erased it; the grid had bent around it. From above, it didn’t look like disorder so much as accommodation. The lights still worked. Nothing collided. Whatever this was, it seemed less like control than cooperation.

The city’s name began to amuse me. Phoenix usually calls up images of fire and rebirth, of destruction followed by renewal. But nothing I was seeing looked remotely apocalyptic. No burning, no rising—just a city continuing. The symbol promised drama; the reality delivered maintenance. I found myself oddly relieved by that.

Later—after work, in that familiar hour between jest and earnest—the coincidence train kept rolling. Demian drifted back into mind, not as a character so much as a voice, speaking to me as he once spoke to Emil Sinclair. You’re still expecting fire, he seemed to say. But Abraxas isn’t a sequence. He doesn’t destroy and then create. He holds both at once.

Seen this way—as a series of near-misses rather than revelations—felt right, and I couldn’t help smiling at how neatly things were lining up. The grid and the older road. Olympus standing outside time. Ragnarök waiting inside it. Abraxas, as Jung described him, wasn’t about rebirth after annihilation, but totality—light and dark, order and chaos held together. Not the phoenix that burns and rises, but something closer to a phoenix that simply lives with its fire.

At some point I had to laugh. I’d managed to notice two birds at once—the phoenix and Abraxas—and for a moment it felt like a metaphysical version of killing two birds with one stone. Except nothing was killed, no stone was thrown, and the person most affected was probably me. I may have been a little stoned that night. Still, the insight stood: not competing symbols, but a single frame wide enough to hold both. If that’s pronoia, it isn’t the belief that the universe is on my side. It’s the simpler realization that sometimes things line up—and noticing that doesn’t require certainty, only attention.

That memory led me, oddly enough, to an old wartime artifact—as if the same lesson had been written for very different circumstances: a German Tiger tank training manual.

It was another system built not to triumph, but to endure pressure without moral theatrics.

It used humor to instruct operators of a fifty-ton vehicle designed to survive chaos. This was not the posture one expects in the middle of a blitzkrieg. The manual warned against moroseness and moral grandstanding. Humor, it suggested, was not a luxury but a stabilizer. The machine required seriousness without sanctimony. So did the men inside it.

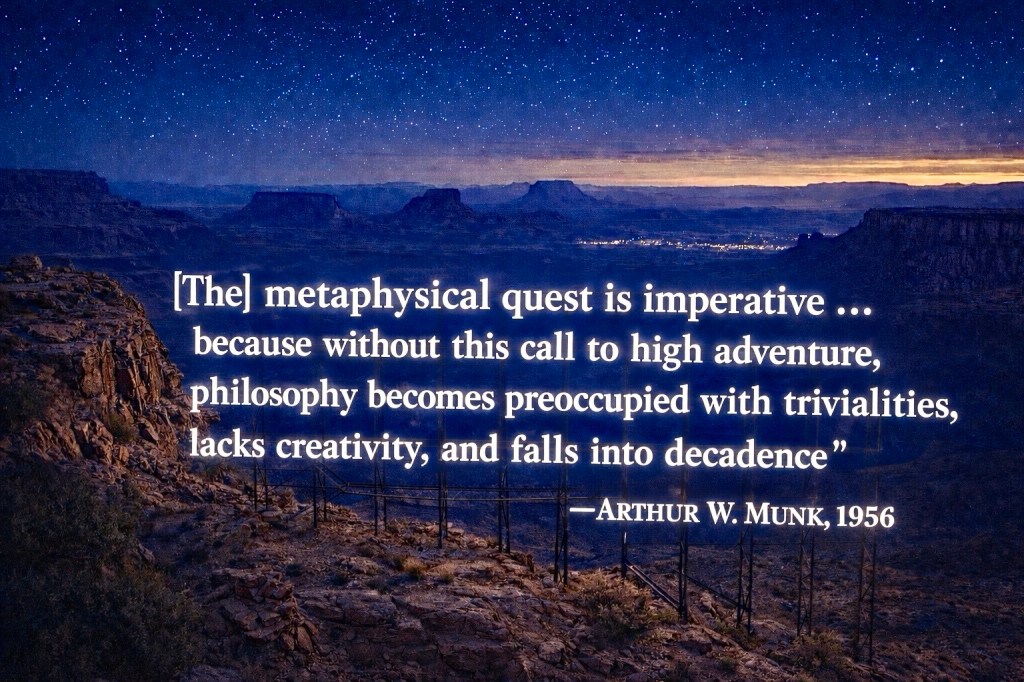

Later, I came across a line written in 1956 by Arthur W. Munk—an appropriately monastic name for the sentiment he expressed. He argued that without a metaphysical sense of adventure, philosophy collapses into triviality and decadence. I took this less as a rallying cry than as a maintenance warning. Thought, like machinery, corrodes when it forgets why it exists.

Not long after that, we witnessed a total solar eclipse. The Moon, at precisely the right apparent size, covered the Sun completely. This alignment is unnecessary for life. It performs no survival function. It exists only to be seen. The tolerances involved are uncomfortably tight. It is the sort of precision that invites awe without offering explanation. And for a moment—only a moment—it felt as though the world was allowing itself to be looked at.

Which brings me, finally, to a thought I resist even as I write it: the Earth seems conveniently well-stocked for our survival and use. Water behaves itself. Carbon is cooperative. The atmosphere is breathable. The warehouse appears supplied before the job was announced. I don’t know what to make of this, and I am not necessarily claiming intent. I am only noting adequacy. But adequacy, sustained over time, begins to feel less like accident and more like allowance.

Perhaps pronoia is not the belief that the universe is conspiring in our favor. That would be childish. Perhaps it is merely the recognition that the system makes room for us—often quietly, sometimes extravagantly—and that recognizing this fact carries a responsibility as well as a comfort.

If that is so, then the proper response is not only reverence, and certainly not denial, but attention: to keep the bed made, the air moving, the traffic flowing, and the questions alive—not because we are afraid of collapse, but because things have, improbably, been allowed to hold.

—Filed by The Accidental Initiate (with field supervision by John St. Evola, M.O.O.)

Leave a comment