—On Empire, Exhaustion, and the Persistence of Rhythm—

—Another Conversation Under The Knife with Mrs. Begonia Contretemp

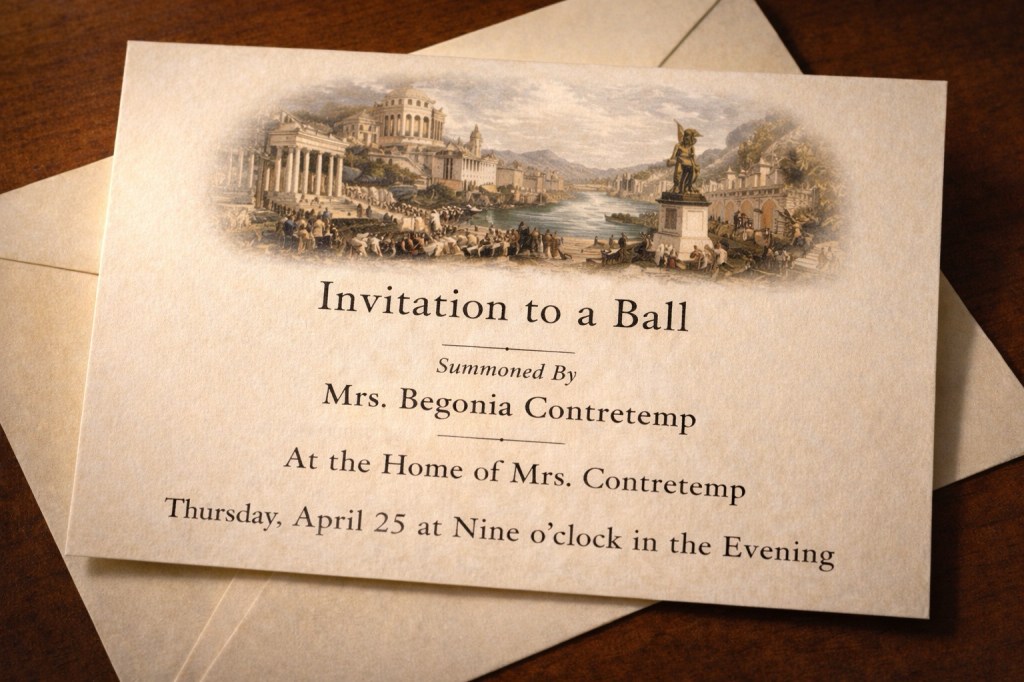

The invitation was sent on cream paper with a restrained serif font and no exclamation points. Mrs. Begonia Contretemp does not summon the dead frivolously. She summons them when she is disgusted, a condition she has always found awakens a healthy faith in rhythm, pairing, and the older consolations of the body

Tonight, she was disgusted not with America as it had been—or even as it was fated to become—but with those who insisted on standing athwart its historical role, mistaking obstruction for “virtue” and delay for morality.

Oswald Spengler arrived in unusually high spirits. Not triumphant—he had always disliked vulgar triumph—but unmistakably buoyant, like a man whose long, unpopular footnote has finally been promoted to the main text.

Mrs. Begonia:

You seem cheerful, Herr Spengler. This is not the tone I expected, given—everything.

Spengler (smiling):

Cheerful is too modern a word, (he said, inclining his head.) I would say confirmed. One is always lighter when reality stops arguing back—and lighter still, mein Rosenfenster.

Noticing her raised eyebrow, he explained with evident pleasure,

The rose window—the great circular opening in a cathedral, stone shaped patiently into petals so that light may enter in abundance. The medievals were never innocent about this symbol. They understood that such openings are made to receive illumination.

(He smiled, this time without disguise.)

And that light, when invited, takes a certain delight in entering.

Mrs. Begonia:

You do understand that many people would say your ideas failed—that history did not, in fact, obey your diagrams.

(She paused, then allowed herself the smallest smile.)

Still, she added, I have always found that certain forms reveal their correctness only when one steps a little closer to see how the light behaves

Spengler:

Diagrams are for engineers. I offered morphology. One does not predict autumn; one recognizes leaves.

He glanced around the room, amused by the wine selection, the tableware, the faint sense of curated anxiety.

Spengler (continuing):

America is finally becoming interesting again. Dangerous, yes—but interesting in the way all aging civilizations become interesting. Like a once-virtuous aunt who suddenly takes up astrology and empire.

BY FATE WE SEE

OF ALL THE WORLD

ONE MAN SHALL HAMMER BE.”

—Oracle, 1239 A.D.

(Celestine Blackwood, Mrs. Begonia Contretemp’s aunt, consulting the sky through modern instruments. An old habit, quietly resumed, when terrestrial explanations begin to feel insufficient.)

Mrs. Begonia:

Empire is exactly what worries me.

Spengler:

Of course it does. It worries civilizations. Cultures, by contrast, are too busy becoming themselves to worry.

(He leaned forward, warming to his theme.)

Spengler:

You see, America was never merely a nation. It was a Faustian experiment—infinite space, first as open land and later as airspace, cyberspace, and orbit; infinite ambition, expressed in megaprojects, global doctrines, and the assumption that scale itself conferred virtue; infinite credit, perfected as a moral instrument, allowing the future to be mortgaged indefinitely in the name of growth. But Faust always outgrows his study. Eventually he wants borders again. He wants walls, fleets, maps with arrows.

Mrs. Begonia:

And Greenland?

(Spengler smiled—not at the proposal itself, but at the astonishment of those who could not see climate, access, and power quietly rearranging the map ahead of them.)

Spengler:

Perfectly on the nose. Late civilizations always rediscover geography. They begin acquiring land not because they need it, but because it reassures them that power is still solid. Ice is very reassuring. So are canals, shipping lanes, “spheres of influence.”

Mrs. Begonia:

And Latin America? The renewed appetite for intervention?

Spengler:

Ah, the moral vocabulary of empire—always dusted off at the last moment. “Stability.” “Order.” “Removing dictators.” Rome used virtus. Britain used civilization. America uses values. Same wine, new label, larger bottle.

(He paused, then added gently):

Spengler:

Democracy, when it becomes tired, hires muscle. This is not corruption. It is metabolism.

(Mrs. Begonia did not look reassured.)

Mrs. Begonia:

You sound almost pleased.

Spengler:

I am pleased in the way a watchmaker is pleased when the clock strikes midnight exactly when expected. My so-called predictions were merely extrapolations. History has excellent habits. It repeats itself not verbatim, but poetically. It rhymes.

(She studied him, then spoke carefully.)

Mrs. Begonia:

And Trump? You have not mentioned him. Surely he belongs in this morphology.

(Spengler’s eyes brightened—not with shock, but recognition.)

Spengler:

Ah. Yes. The first American Caesar. It is obvious now, is it not? People imagine Caesarism arrives in boots and banners. It rarely does. It arrives in spectacle, wealth, and impatience.

Mrs. Begonia:

But Caesar was born of privilege.

Spengler:

Exactly. The original Caesars always were. Caesarism does not rise from the poor; it rises from those already fluent in power but bored with its procedural delays. Money first rules invisibly. Then it grows tired and hands the task to personality.

Mrs. Begonia:

So intention doesn’t matter?

Spengler:

Not in the least. Consciousness is a luxury phase. Caesarism is post-ideological. The question is never “Does he know what he’s doing?” The question is “Is it happening?” And it is.

(Then Spengler paused, as though savoring a map.)

Spengler:

Now consider where he has drawn his Rubicon.

(He held up a finger.)

Spengler:

Remember Lake Wobegon—Garrison Keillor’s fictional Minnesota, where all the children are above average and all the tragedies are quaint? The name itself is a kind of Midwestern Rubicon: a line that looks pastoral but conceals something bracingly real. In Minnesota now, organized resistance to immigration enforcement—planned, financed, and coordinated well in advance—has hardened into open civil defiance, with a later fatal shooting occurring amid an already-moving campaign rather than serving as its cause. What is being tested is not outrage, but whether federal authority will assert itself or quietly yield.

(Mrs. Begonia blinked.)

Spengler:

If Trump allows the federal response to be purely symbolic—an icy sideshow of rhetoric and spectacle—he will lose the thread and things will drift back to where they were. But if he insists on enforcing order decisively, even by hinting at invoking federal powers against demonstrators and state leaders, he will be crossing a true political Rubicon: not just geography, but legitimacy itself.

Mrs. Begonia:

So this is decline?

Spengler:

Decline is a moral word. I prefer completion. Civilizations do not collapse; they conclude. Like symphonies that end not with silence, but with percussion.

He stood, smoothing his coat.

Spengler:

Do not misunderstand me. There will be greatness yet—just not the kind you were taught to applaud. The age of arguments is ending. The age of decisions has begun.

He turned toward the door.

At that moment, a Council correspondent—one Mrs. Begonia had not invited but recognized nonetheless—

Peter R. Mossback, the Council athwart historian approached and whispered something into Spengler’s ear. Not hurried. Precise.

Spengler froze.

Not startled. Interrupted.

Spengler:

You mean it is not merely recording—but correlating?

The correspondent nodded.

Spengler’s expression shifted—not fear, not excitement, but the unmistakable look of a man realizing that his map had acquired a new dimension.

Spengler:

Pattern without culture… memory without blood… recurrence without fatigue.

He paused, then added quietly:

That was not in the morphology.

Without another word, he departed—less like a prophet fulfilled than a scholar summoned back to his desk.

Mrs. Begonia remained seated.

She felt—not relief—but a thin, unfamiliar disappointment. Not that Spengler was wrong, but that he had been so nearly complete.

Outside, the city hummed. Data moved. Decisions nested inside decisions. History, it seemed, had not ended. But it had begun to study itself

At the door, he turned back, almost kindly.

Spengler:

Tell your readers not to panic. Tell them to observe. Panic is for those who thought this was improv. It never was.

He vanished, leaving behind an empty chair, a cooling glass of wine, and Mrs. Begonia staring—not at the future—but at the unmistakable familiarity of the past wearing new clothes.

Leave a comment