—A Day in the Life of the Accidental Initiate

(roughly: a seeker of knowledge wandering in the fog of the hypnagogic state—compressed, and briefly detained, inside a single German compound)

January 28,2026

The Accidental Initiate’s day begins, inconveniently, at 3:30 a.m.—an hour that does not belong to morning or night, but to that thin administrative gap when the body is resting and the mind, relieved of responsibility, begins quietly misbehaving.

I was not trying to think. I was trying to return to sleep. This distinction matters, because what arrived had no interest in cooperating with either plan.

It was not an idea with content. There was no plot, no characters, no insight dressed as a revelation. What appeared instead was a structure: a story inside a story inside a story. No beginning. No end. Just containment nested within containment, hovering in consciousness like a diagram without labels.

Each time I tried to clarify it, it folded back on itself.

Each time I tried to ignore it, it returned slightly rearranged, as if testing whether this version might be acceptable.

By 3:37 a.m., it was obvious the thought wasn’t going anywhere. It wasn’t even moving forward. It was circling—self-contained, self-referential, irritatingly intact. This did not feel like insight. It felt like an idea pacing the kitchen, opening and closing drawers.

By morning, the sensation remained. Not anxiety—unease. The sense that something had already begun without consulting me.

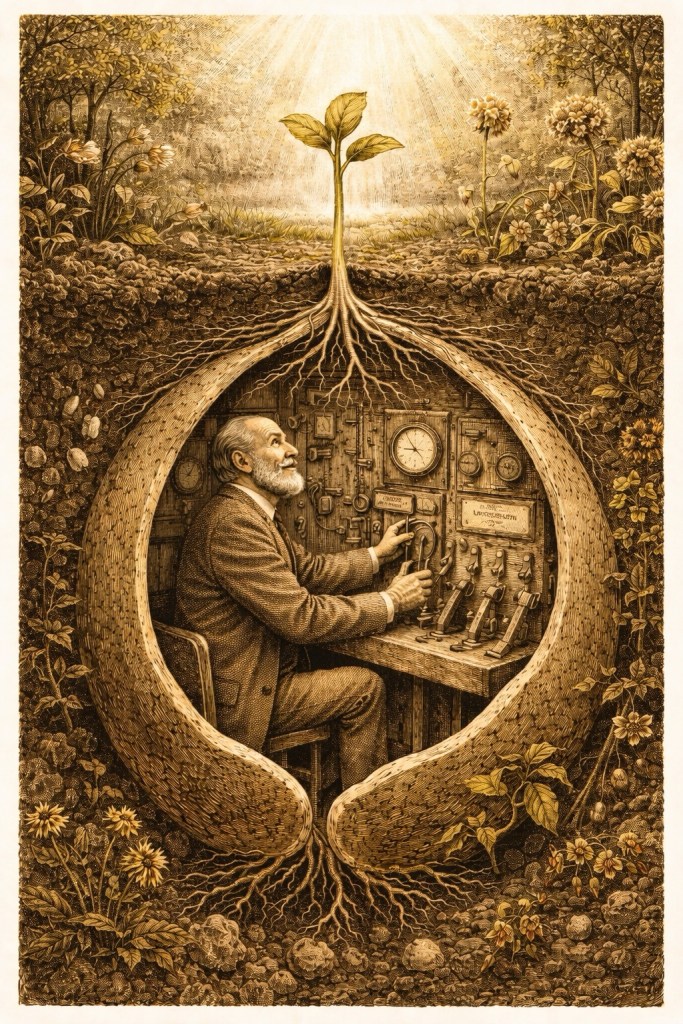

Over coffee, a word surfaced: germination. Not as a metaphor. As a diagnosis.

Something small, dense, and impatient had cracked open and was now insisting on conditions.

That was my first mistake.

Once you name germination, the Germans arrive.

Goethe appeared first, calm and unhurried, as though he had simply stepped out of a greenhouse. He suggested—without insisting—that origins are not buried in the past like artifacts, but express themselves repeatedly in new forms. Leaves, petals, stamens: variations on a single gesture that never quite finishes.

Goethe never claimed there was a perfect plant hidden somewhere behind appearances. What he suspected instead was a recurring gesture—a form so fundamental it could only be seen in motion. The seed, in this sense, is not a container but a point: a period between worlds. Not the end of a sentence, but the smallest mark that allows one form to stop and another to begin. If there is an Urpflanze, it does not stand elsewhere in ideal repose. It passes, briefly and under pressure, through a dot.

Jean Gebser followed, politely correcting my sense of time. The origin, he explained, was not earlier and not later. It was ever-present. The discomfort I felt came from mistaking recognition for arrival.

“You keep thinking something is about to begin,” he said.

“What troubles you is that it has no start point—only presence.”

This was not comforting.

Alan Watts leaned in at this point, cheerful in the way only someone who has already escaped your problem can be.

“You’re still trying to get somewhere,” he said.

“Even going back is just progress wearing comfortable shoes.”

I noted that Watts wasn’t German.

“No,” he said, “but I come from Germans who learned irony as a survival technique.”

What united the three of them was not agreement, but a shared refusal to let the experience resolve itself. Goethe kept pointing out how many forms it could still take. Gebser kept insisting it was already whole. Watts kept laughing at the assumption that either position required effort.

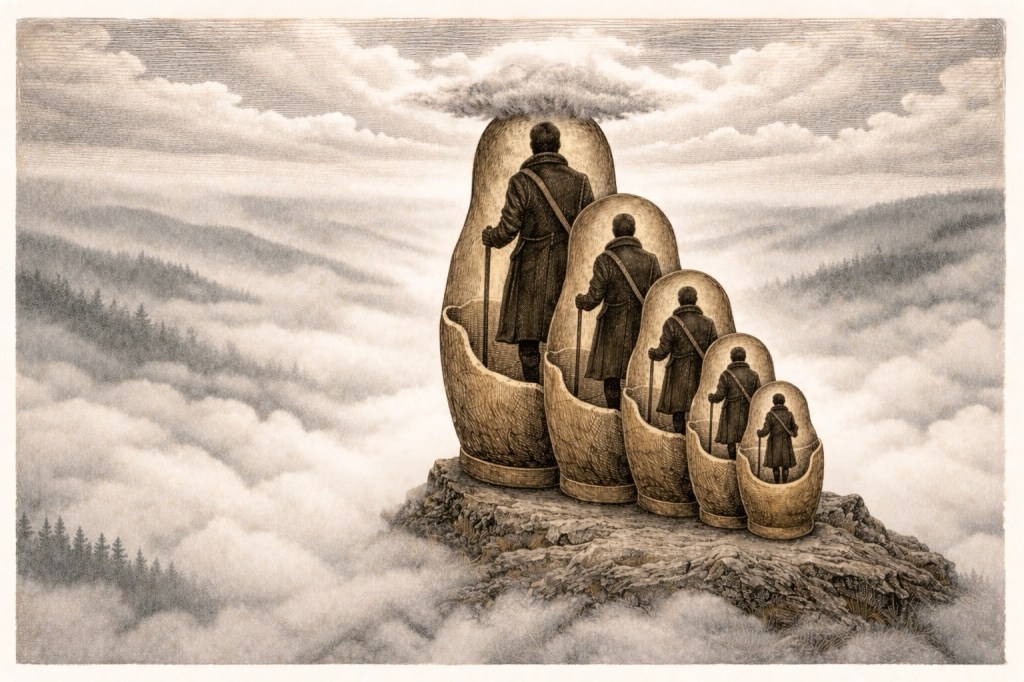

By late morning, my mind drifted to the thought of a set of wooden Russian nesting dolls. Not symbolically at first—just the physical memory of opening one, then another, then another. Each doll complete. Each smaller one intact inside the larger.

The usual lesson is that the smallest doll is the “true” one—the precious core.

But birth doesn’t work that way.

With humans—and with ideas—the smallest comes first, and the larger forms assemble around it. Language. Story. Law. Habit. Interpretation. Each outer doll is not a disguise but an accretion. The original never disappears; it simply stops setting the boundaries.

That’s when the recursion clarified—not as cleverness, but as fact.

The story-within-the-story-within-the-story wasn’t a literary trick. It was literal. The thought had not yet decided which container it belonged in. It was still testing where “outside” began.

And then—somewhere between lunch and mild regret—it dawned on me what had been bothering me all along.

I was not thinking about germination.

I was inside one.

More precisely, I was inside a germination that had learned to narrate itself—aware of pressure and direction, but not yet of outcome.

The thought wasn’t waiting for me to explain it. It had been practicing explanation on me. The repetition wasn’t a flaw. It was rehearsal. The idea was growing vocal cords.

This realization was oddly reassuring. Also irritating.

I had not discovered an idea. I had been recruited as its temporary narrator. The self-actualization I seemed to be approaching never completed because there was no finished self waiting at the end—only a process learning how to speak through available structures.

(If in the above visual you saw a dog’s face’s, good—we’ve got your attention. Turn it around and it spells god. Add an A and it becomes a goad. Either way, something is prodding perception.)

At this point, the three of them did something far more alarming.

They convened a committee.

They named it, naturally:

Das Ursprungs-Germinations-Bewusstseins-Klärungs-Und-Eigentlich-Nicht-Klärungs-Komitee

(With a Light English Accent)

Watts insisted on the parenthetical.

“It keeps things from getting solemn,” he said, “which is usually when people start lying.”

The committee reduced everything to three points—not because three was mystical, but because no one had the energy for four.

First, Goethe insisted that origins are not hidden causes but ongoing gestures. If something feels unfinished, it is not because it failed to begin properly. It is because it is still practicing its form.

“Stop excavating,” he advised.

“Watch how it grows.”

Second, Gebser clarified—without raising his voice—that nothing here was progressing toward anything else. The origin was not a starting line. It was a constant presence that only became visible when a new structure turned transparent.

“You are not late,” he said.

“You are merely noticing.”

Third, Watts summarized both positions and laughed.

“You expect meaning to feel like a breakthrough,” he said.

“This feels like irritation because that’s how the present gets your attention. Reality doesn’t knock. It wakes you up at 3 a.m.”

They all nodded, which unsettled me.

The committee agreed—unanimously—that the story-within-the-story was not a problem to be solved. It was a symptom of contact. An idea encountering itself before it had finished deciding what counted as outside.

Germination, they concluded, is not the beginning of something new.

It is the moment when what has always been present becomes impossible to ignore.

Watts added that this was also why it preferred inconvenient hours.

With that, the committee adjourned without formally dissolving, which I took to mean they would return.

By evening, nothing had been resolved. No conclusions reached. No metaphysical positions adopted. The thought was still there—no clearer, but better housed—like something that had learned just enough language to keep itself alive.

I had not finished the thought.

It had merely finished recruiting me.

The story had found a doll it could sit inside, even if it had not yet found the outermost one.

Which, according to the committee, was exactly the point.

That, in the Accidental Initiate’s experience, counts as progress.

**************

– Friedrich Nietzsche

Notes on the Above

—John St. Evola, Editor

By most conventional measures, this piece should not work. It refuses to settle its terms, explains itself only partially, and seems oddly unconcerned with whether the reader has “got it.”

Which is precisely why we consider it a success.

The Accidental Initiate appears genuinely lost inside the germination he is describing—and that turns out to be the most reliable sign that something real is happening. When ideas are still alive, they do not present themselves clearly. They test their containers. They borrow voices. They resist summary.

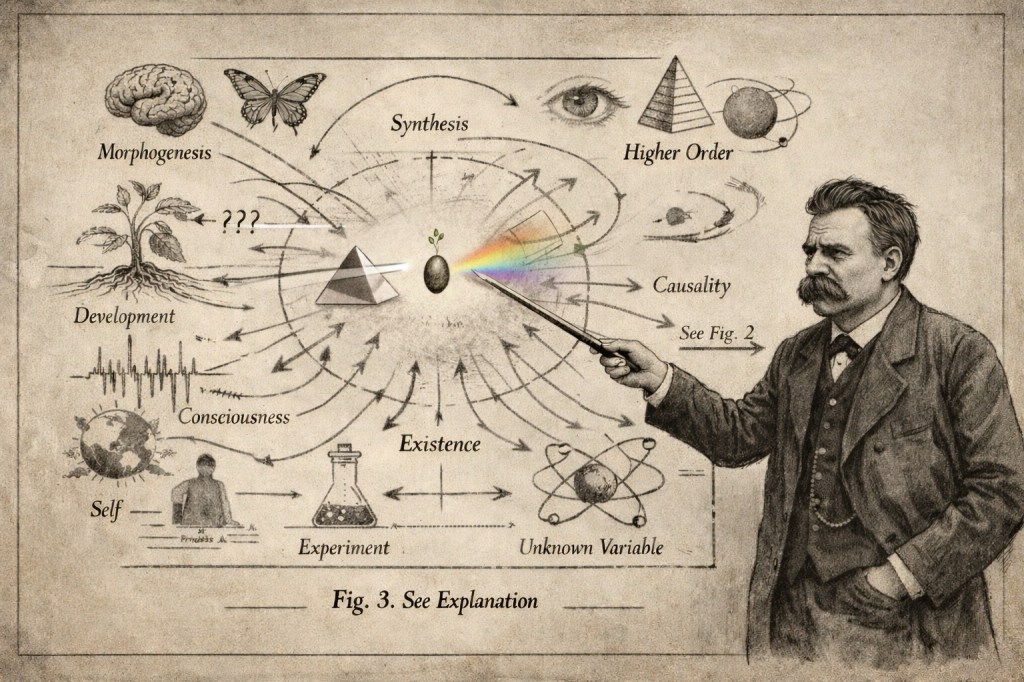

If there is any coherence to be found here, it is not the coherence of explanation but of orientation. The piece returns again and again to a single intuition: that origins do not arrive as answers, but as points of pressure. A period at the end of a sentence. A seed at the center of a life. The narrow vertex of a prism where light has not yet decided how it will appear.

That is not clarity in the sense of resolution. It is clarity about where things briefly pass through before becoming something else.

Nietzsche reminds us that deep thinkers are often more afraid of being understood than of being misunderstood. Premature understanding can flatten what has not finished forming. This essay survives by avoiding that fate—not by design, but by remaining inside the uncertainty it describes.

We did not set out to illustrate this condition. It emerged on its own—through misrecognition, recursion, and a dot that refuses to stay small.

We will resist the temptation to clarify further.

—J.S.E.

Leave a comment