—THEATRE OF GOOD INTENTIONS—

Notes Toward a Political Science of Ruins

The Accidental Initiate had not planned to take that street. The Council was officially on a group tour—cathedrals, museums, orderly lunches—but he had wandered away—in his psychogeographic way—as he tended to do, preferring to slip in time and walk without an itinerary.

He liked seeing cities when no one was explaining them. Vito, it turned out, had also gone missing from the group, though in the opposite manner: not to wander quietly, but to stand still somewhere public and do what he did best with a bullhorn.

pardon my French—

I can’t believe I just said penchant.

It means a habit. A tendency. Something you keep doing.

So yeah. It fits.

The Accidental Initiate continued cutting through the city the way one does when time loosens its grip—following light, avoiding crowds, letting chance make small decisions. In Würzburg, this meant drifting along streets that subtly bent around absences, plazas that felt slightly overwide, façades too orderly to be old. The city guided him without asking, its postwar geometry carrying faint instructions from what had once been erased. That was when the voice reached him, flattened slightly by electronics.

Every. Single. Time.

Not a chant. Not a slogan.

A sentence, repeated like a count taken aloud.

On the corner stood Vito Haeckler, jacket zipped, name tag askew, megaphone raised with the casual authority of a man calling out weather conditions. He wasn’t arguing. He wasn’t persuading. He was reporting.

“Maybe only democracies can attain the prosperity to destroy cities,” Vito said, then said it again, as if the words needed open air.

Vito listed names—Dresden, Atlanta, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Würzburg, Gaza—not rhetorically, but geographically. Points placed on a map already drawn.

Then came the part that stopped the Accidental Initiate mid-step.

“The destruction was egalitarian,” Vito said plainly. “Hospitals. Apartment complexes. Coffee shops. Schools. It didn’t matter.”

No metaphor. Just enumeration.

The Initiate noticed how strange it was to hear egalitarian used this way—not as aspiration or virtue, but as description. The bombs did not discriminate. They flattened almost everything evenly. In that narrow, lethal sense, the destruction had been fair.

Vito repeated the observation, unchanged.

Every. Single. Time.

Standing across the street, the Accidental Initiate felt the familiar widening.

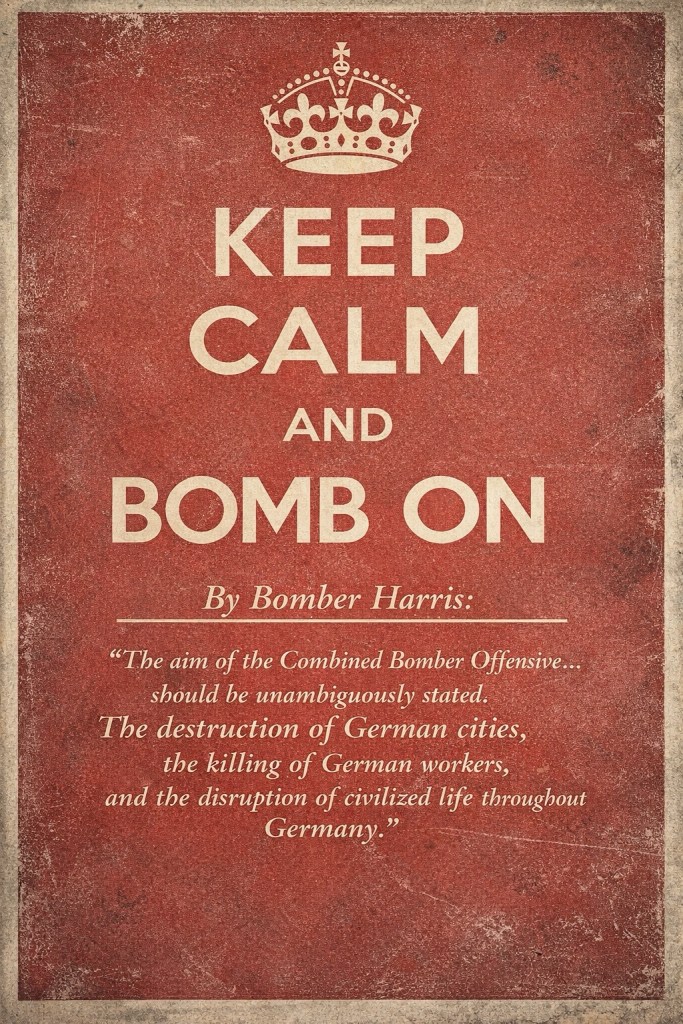

He realized Vito was not saying only democracies can destroy cities, but that only democracies have destroyed cities like this in modernity—by air, by system, by schedule.

And the observation did not stop with the past.

Würzburg stood intact around him—beautiful, corrected. A city comprehensively destroyed and carefully rebuilt. Churches restored. Streets rationalized. Memory curated. It occurred to him, with a flicker of dark amusement, that the same democratic machinery capable of flattening a city was also remarkably good at rebuilding one—with plaques, zoning committees, and tasteful benches explaining what had once stood there.

Destruction on one end. Urban renewal on the other. They liked it from both ends.

His thoughts wandered—backward, sideways—into deeper time. He remembered reading that in Neolithic Old Europe entire settlements show repeated burn layers, houses reduced to ash and then abandoned. Archaeologists still argue whether those places were destroyed by invaders or deliberately burned by their own inhabitants as part of a cycle of renewal or departure. The record does not resolve the question. It simply shows fire, movement, and continuity elsewhere.

He realized he had been trained to read fire only as catastrophe, and still could not quite stop.

What lingered with him was that the cultures of Old Europe are often described as relatively egalitarian—sometimes even matrilineal—less hierarchical than what came after. No obvious kings. No towering fortifications. And yet: organized destruction, followed by collective relocation, apparently survivable.

Paving material generated for the road of good intentions.

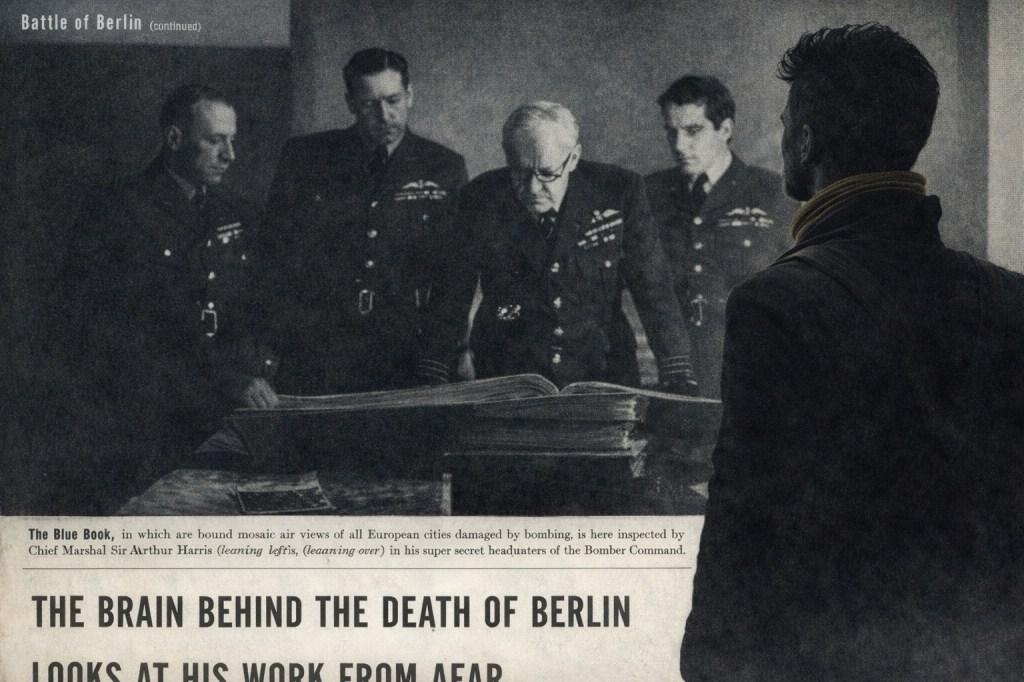

The rubble was cleared by the Trümmerfrauen—German women conscripted into postwar labor to remove it by hand.

He thought, too, of the Iroquoian villages of what is now New York and Ontario—longhouse settlements periodically dismantled, burned, and moved by their own occupants. This was not collapse. It was practice. Decisions made in council. Consensus reached. Soil exhausted, circumstances changed, and the people moved on together. The Iroquois Confederacy itself was famously participatory, often cited—rightly or wrongly—as a model admired by later democrats.

Fire, departure, continuity. No insistence on rebuilding on the same spot. No obligation to explain the past to itself.

Democracy, by comparison, seemed unable to leave a place alone. It destroyed, rebuilt, straightened, annotated, and normalized—whether through bombs in wartime or through neglect, addiction, administrative drift, and slow infrastructural failure in peace.

The Initiate could see how someone might conclude that democracy destroys cities. The evidence tempted the conclusion: spectacularly in war, quietly in peace. He could not blame anyone for reaching it.

And yet he stopped short.

Because what Vito was doing—what he continued to do, megaphone raised—was not declaring a law of history. He was pointing at a record. A pattern that recurred often enough to be noticed, but not yet enough to be settled.

Vito reached the end of the observation and began again.

Every. Single. Time.

The Accidental Initiate moved on—not because the thought had resolved, but because it hadn’t. Some observations were not meant to harden into positions. They were meant to be encountered again, from different streets, at different speeds, until one could tell whether the pattern was structural—or simply unfinished.

Behind him, Vito kept counting. Not condemning. Not defending.

And I, the Accidental Initiate am just noticing, too.

Leave a comment