A Council Meditation on Amphibians, Algorithms, and the Long Arc of Corralling Frogs.

By The Grouchy Marksman

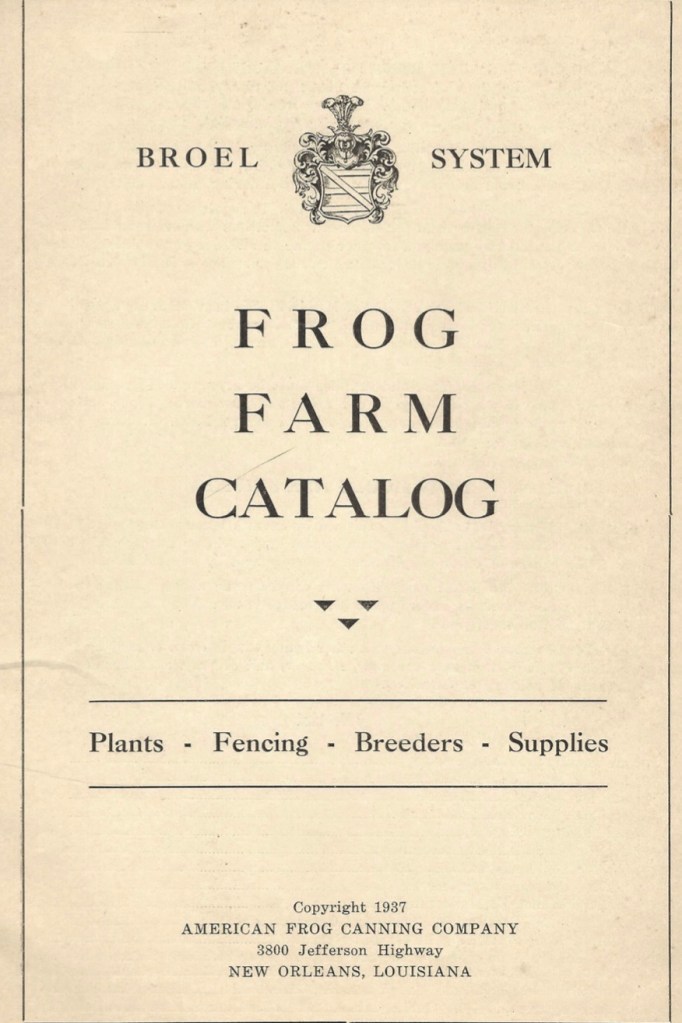

“Frog raising offers a fascinating and profitable hobby that can easily grow into a full-time occupation.” —Albert Broel, Frog Raising for Pleasure and Profit, 1936

“They’re just ironic frogs—until they hop into Congress.”—Modern Media Analyst, 2024

⸻

I. The Depression-Era Frog Farm: Hope with Webbed Feet

In 1936, amid the economic mire of the Great Depression, Albert Broel published Frog Raising for Pleasure and Profit. This wasn’t just a novelty pamphlet—it was a bootstrap blueprint for small-pond dreamers.

At a time when New Deal programs promised collective uplift, Broel spoke directly to those craving private salvation through muck and reeds. Frogs, he explained, needed little space, fed on bugs, and could be sold for food, science labs, and even leather goods.

It was:

Microenterprise before Etsy

Homesteading before TikTok

Alternative protein before Silicon Valley got weird about it

Broel’s model was simple and stunning:

Dig a backyard pond. Hatch a batch of tadpoles. Sell legs to restaurants, specimens to schools, hides to leather dealers. Repeat

A swamp-to-table hustle before branding ever caught up.

But where the Great Depression of the 1930s was economic, today’s frog-raising unfolds in a depression of meaning. Back then, people needed protein. Now, they need purpose. Albert Broel’s readers were scraping for literal sustenance—today’s frogfluencers are grasping for symbolic survival in a collapsing infosphere. What gets bred isn’t food, but identity, irony, and influence. And beneath the memes and monetization lies a deeper current: the existential survival of European-derived peoples, adrift in a world where cultural continuity is treated as suspect and irony is the last permitted inheritance.[1]

What was once seen as a bootstrap hustle—or possibly a swampy little scam—has evolved, with tragicomic flair, into a postmodern necessity. It may be comical. It may be exploitative. But in the meme-saturated terrain of the 21st century, frog farming is no longer optional—it’s survival by other means. Back then, you sold frogs because you were desperate. Now, you are the frog—branded, memed, livestreamed, and still trying to hop your way out of the muck.

⸻

II. Now Enter: The Meme Frog

Nearly a century later, frogs are once again being raised—but this time, not for meat.

They’re being memed, monetized, and militarized online.

Pepe the Frog—originally a chill cartoon slacker—morphed into a layered symbol: ironic mascot, chaos agent, political provocation.

The frogs are no longer in ponds.

They’re in comment threads.

On T-shirts.

On livestreams.

And yes—they’re monetized.

Today’s frog wranglers operate with ring lights, not nets.

They’re not raising amphibians for biology class—they’re breeding engagement, subscriptions, and the occasional cultural firestorm.

And like Broel, they’ve built a business on a creature most people overlooked.

⸻

III. Funnels, Frogs, and the Swamp as Business Model

Broel meticulously managed his frogs through life stages: tadpoles, young frogs, breeders.

The stages of frog farming—and follower farming—aren’t so different.

Tadpoles → Casual viewers

Young Frogs → Subscribers

Breeders → Donors / Acolytes

Modern influencers? Same structure—different species.

Whether it’s pond temperature or audience engagement, the principle is the same:

Manage the ecosystem.

Know your frogs.

Feed them just enough.

Never let the water stagnate.

It’s still a swamp. But it’s your swamp—if you play it right.

⸻

IV. Is It Still for Pleasure and Profit?

The irony? Both Broel and the frogfluencers promise a kind of autonomy.

In the 1930s:

“Be your own boss—with bullfrogs.”

In the 2020s:

“Monetize your memes. Livestream your truth.”

Frogs, after all, are creatures of metamorphosis.

Some get flipped for profit.

Some croak under scrutiny.

Some leap into public life—only to be devoured by the very audience that spawned them.

Albert Broel may not have foreseen Pepe.

But he would’ve understood frog economics.

He knew frogs multiply.

That certain ponds are profitable.

And that once the public gets a taste for frog—someone’s going to start breeding them.

Whether for the table or the timeline.

⸻

V. Council Notes

Albert Broel died in 1976. But his model hops on—in homesteading zines, survivalist YouTube, and frog-themed Discord servers.

His 1936 booklet remains in circulation among amphibian nostalgists and microenterprise romantics:

Frog raising for pleasure and profit

The species have changed.

The stakes have changed.

The swamp? Still the same.

“Keep your breeders healthy.

Keep your pond clean.

Never underestimate the frog.”

FOOTNOTES

[1]Irony as the last permitted inheritance — a phrase used in Council documents to describe the condition wherein certain cultural or ethnic groups are allowed to reference their origins only through satire, parody, or self-effacement. Direct expressions of continuity, belonging, or pride are pathologized or policed—unless filtered through ironic detachment. What was once lineage is now only tolerated as “content.” Thus, the children of Europe inherit not land, nor language, but memes—with an implied smirk. In such a world, irony is the only will that still gets notarized.

—The Grouchy Marksman

[The Grouchy Marksman writes with precision and restraint—his targets are cultural contradictions, and his ammo is irony. Best known for “Frog Raising for Pleasure and Profit” and “A Spectre is Haunting the World,” he traces the absurd overlap between ecology, ideology, and identity.

He doesn’t shout. He aims carefully. And more often than not, he hits what others pretend not to see.]

***

Free download:

Everything you will ever need to know about the history of frog farming.

Leave a comment