—Peter R. Mossback: On the Chromatic Leasing of the World—

It takes a special kind of century to look at color—the oldest public domain on Earth—and decide it ought to come with a licensing fee. Pantone began as a fix for a practical problem: too many people arguing about what “blue” meant. Fair enough. But in solving that quarrel, Pantone discovered a deeper truth of our age: if you can standardize something, you can rent it back to the people who once took it for granted.

And the Pantone tax is just one thread in a much larger tapestry. You pay a little extra for the bread bag because the ink matches a corporate swatch. You pay a little extra for the carton because it carries this or that certification — organic, halal, kosher, heart-healthy, dolphin-friendly — every seal a small contractual promise that someone had to verify, approve, and invoice. The labels don’t mention the fee, but the fee is there all the same, baked into the shelf price like a quiet tithe of modern life. You think you’re just buying groceries, but you’re really buying an entire chain of invisible authorizations.

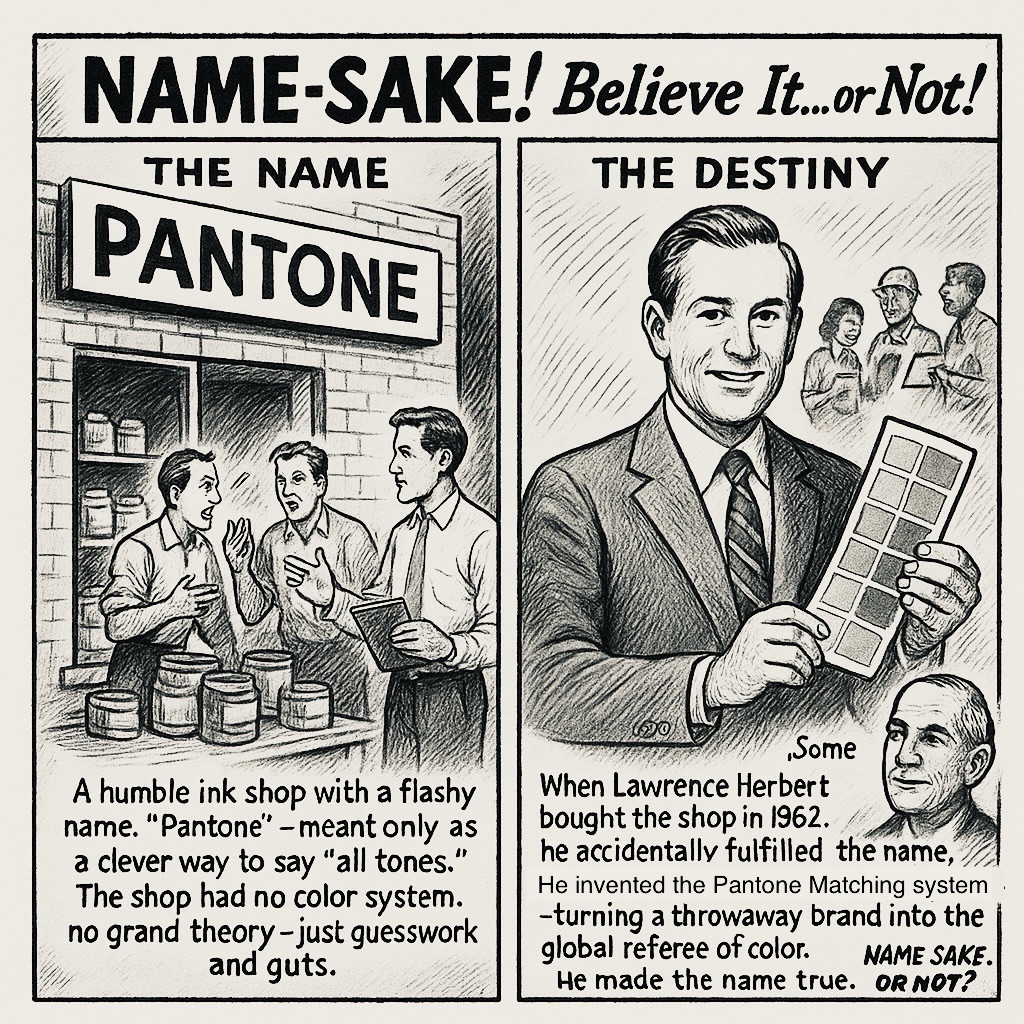

Lawrence Herbert’s Pantone doesn’t sell ink. It sells agreement—a dictionary of hues that the modern world must now consult like scripture. And once a standard becomes indispensable, it becomes profitable. That’s not villainy; it’s the gravity of the system we built.

And perhaps all of this was inevitable. A global economy needs ledgers, precision, reproducibility. Pantone gave the world a language to avoid costly mistakes, and in that narrow sense, it was necessary. But inevitability isn’t innocence. Tools can clarify, but they also centralize. Standards can serve, but they can also extract. You can use the ledger without bowing to it—and you should keep a steady eye on how easily a helpful system becomes a tollbooth.

History offers its own parable. In the old days, con men “sold” the Brooklyn Bridge to hopeful newcomers. A crude swindle. Now the trick is subtler. Whether or not Pantone has ever issued an official code for that weathered granite hue, someone somewhere has tried to name it, number it, and fold it into a fan deck. The bridge once changed hands by fraud; today, its very color could be commodified—leased as a swatch, packaged as intellectual property. Same impulse, cleaner paperwork.

That’s capitalism’s quiet genius: it finds a way to turn even the commons into rentable terrain. Nothing wrong with recognizing its necessity. But don’t mistake necessity for natural law. And don’t ever think you’re buying the bridge when all you’re holding is its color code.

—More from Peter R. Mossback HERE

Leave a comment